An accidental arrival

There are various claims of being the first white explorer in the area—from Jedidiah Smith to Joseph Reddefors Walker. The most comprehensive early accounts come from Lieutenant Tredwell Moore and historians agree he was most likely the first white person to arrive in the Mono Basin in 1852.

Moore wasn’t out exploring for new frontiers. He was pursuing and attempting to capture Chief Teneiya and other members of the Ahwahneechee Tribe. In 1851, by special order of California Governor John McDougall and through a special act of the US Congress, militias received federal and state support to occupy what is now known as Yosemite. This occupation meant the demise of the Ahwahneechee Tribe in Yosemite. Moore’s hunt led his company from Tenaya Lake to the Eastern Sierra where thankfully, he failed to capture Chief Teneiya. Instead, Moore ventured into the Mono Basin, where his findings would forever impact the land. From chronicler Lafayette Bunnell’s Discovery of the Yosemite:

“Lieutenant Moore crossed the Sierras over the Mono trail that leads by the Soda Springs through the Mono Pass. He made some fair discoveries of gold and gold-bearing quartz, obsidian, and other minerals, while exploring the region north and south of Bloody Canyon and of Mono Lake.”

Moore’s explorations and findings were shared in the booming towns of San Francisco and Stockton, thus spurring the interest of miners like Leroy Vining and others, who began to settle in the Mono Basin in the fall of 1852 as they began to prospect and mine.

Prospectors arrive

There was little gold found where Moore had visited by Bloody Canyon, yet the prospectors were not deterred. Gold veins were eventually found north of the Mono Basin in 1857 at the confluence of Virginia and Dog creeks, and the mining town of Dogtown quickly popped up.

Word spread to miners in the West of another discovery between Conway Summit and Mono Lake known as the “Mono Diggings,” which later became Monoville. The Monoville rush was even bigger than Dogtown and between its establishment in 1859 and 1860 the population was estimated to range from 900 to 3,000 people. The town grew despite the lack of water, short mining season, high cost of living, and the long distance to San Francisco. Mines were also established in Lundy Canyon (May-Lundy Mine) and Lee Vining Canyon (Bennettville).

Prospectors continued to push outwards and discovered rich veins of silver about 15 miles northeast of Mono Lake in the fall of 1860, where soon afterward the town of Aurora formed. The town became the county seat of the new Mono County (even though Aurora later turned out to be in Nevada instead of California), and by late 1863 the population exceeded 5,000 people, including one man by the name of Samuel Clemens, also known as Mark Twain. Aurora’s boom was short-lived, however, and by 1865 the mines had closed.

Twelve years later in 1877 the entire population of Mono County was less than 1,000 miners and settlers. That same year however, the Standard Company in Bodie extracted significant profits from a rich vein of ore. The profits created a stir, and within the year the rush was on. By the end of 1878, the population of Bodie would reach 5,000 people.

Bodie’s boom and influence on the Mono Basin

After struggling for nearly 17 years as a tiny, insignificant mining camp, Bodie finally boomed.

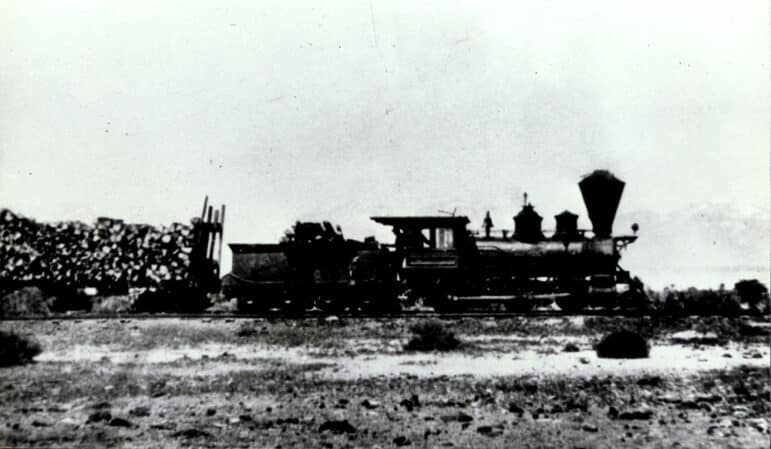

Like its once-booming predecessor Aurora, Bodie needed milled wood for construction, square beams for mine shafts, fuel for stamp mills, and cordwood for heating. With few trees in the vicinity, the cost of bringing wood to the barren Bodie Hills was high. Wealthy men in the Bodie mining community formed the Bodie Railway & Lumber Company in 1881. Like other railroads in the West, the Bodie Railway & Lumber Co. hired inexpensive Chinese labor, much to the outrage of locally unemployed miners. By 1882 a 32-mile-long railroad was in service between Bodie and Mono Mills, running along the east shore of Mono Lake.

The new narrow-gauge railroad was built specifically to bring wood to Bodie. Workers at Mono Mills harvested the big Jeffrey pines growing to the north and east of the Mono Craters, and the railroad brought the wood to market in Bodie. Though the metal rails have long since been sold as scrap, you can still see the old railroad grade not far from the remote eastern shores of Mono Lake.

Lee Vining’s namesake

Prospector Leroy Vining failed to find gold, but did find a fortune in timber. Not long after arriving in the area he established a mill and made a business of selling lumber to local mining towns. His business continued until his unfortunate, accidental death in the mining town of Aurora.

One day after delivering lumber to Aurora, Vining suffered a fatal gunshot wound to the groin. How he acquired the fatal wound is not exactly clear, but one version of the story goes that Vining was fond of carrying a small Derringer pistol in his front pocket and while drinking his profits in the saloon at the Exchange Hotel, the gun somehow went off. The gunshot sent nervous customers out into the street, including Vining himself, who was later found dead a short distance down the road, having bled to death from his wound.

The town of Lee Vining was named after him when people realized the name “Lakeview” was already in use by another post office in California.

Farms flourish to feed the miners

Not everyone who ventured to the Mono Basin came to get rich and exploit natural resources. Many immigrants and ex-miners homesteaded around Mono Lake in the hopes of making a living off the land.

The French Canadian DeChambeau family moved to the Mono Basin in 1880 after living in Bodie for two years (the remains of their ranch are still standing). Anna & Charles Currie came from Minnesota in 1885. Long before the McPherson family settled on Paoha Island and started a goat ranch, a Frenchman by the name of Caesar Thiervierge kept chickens, rabbits, and grew some alfalfa on the island.

Early Mono Basin ranchers often had plentiful food and stock, and were able and willing to supply food to the local mining towns of Bodie and Lundy. Mining finally gave out in the Mono Basin and the Great Depression of the 1930s made successful ranching and farming in the Mono Basin difficult.

With the intention of extending the aqueduct north into the Mono Basin, the Los Angeles Department of Water & Power made tempting offers for land and water rights that few could refuse. Today, the City of Los Angeles is the largest landholder in the Mono Basin after the federal government.

Learn more about Mono Basin history

If you are interested in learning more, the Mono Basin History Museum is a vibrant local resource for local history. We highly recommend making a visit to the museum or visiting their website.

Learn More

Top photo courtesy of California State Parks.