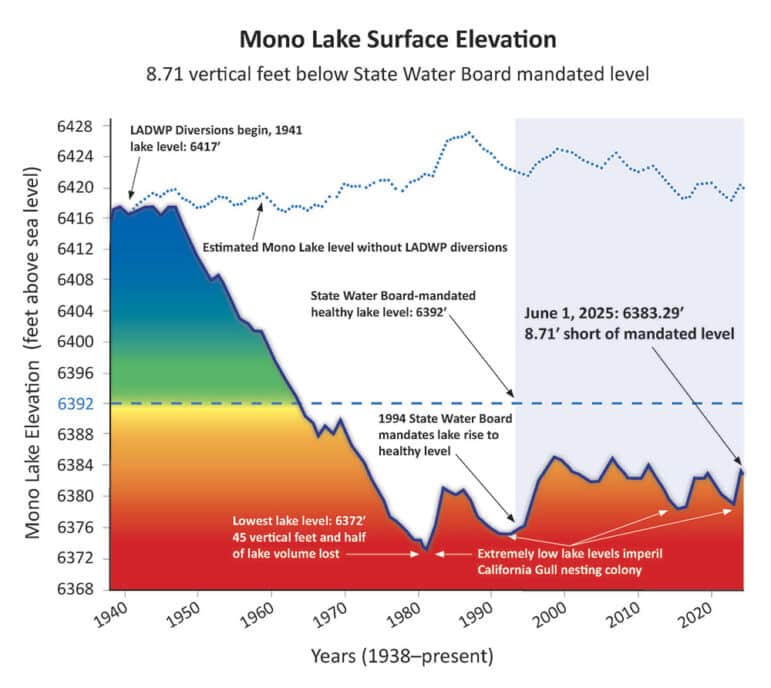

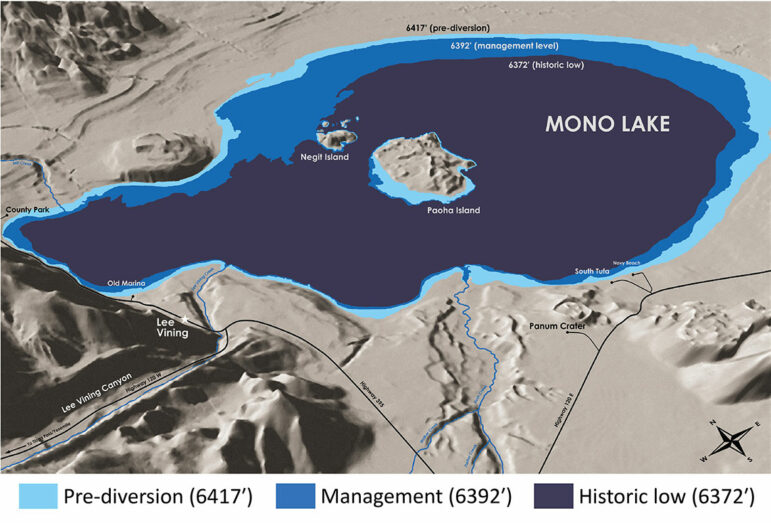

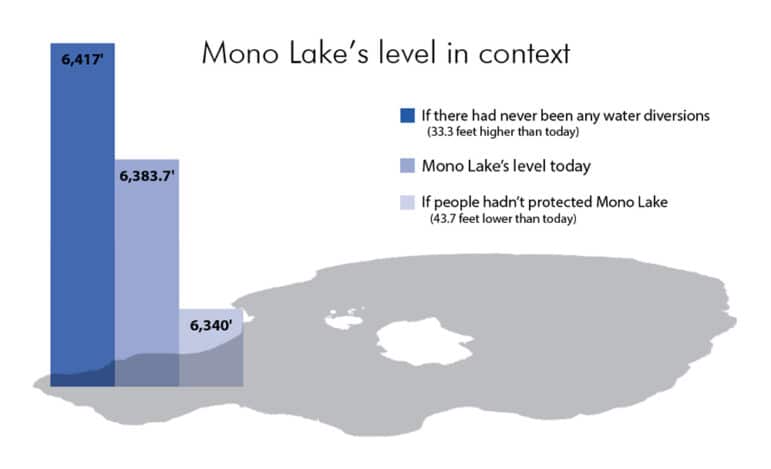

In 1941, the Los Angeles Department of Water & Power (DWP) began diverting water from Mono Lake’s tributary streams, sending it 350 miles south to meet the growing water demands of Los Angeles.

As a result, over the next 40 years Mono Lake dropped by 45 vertical feet, lost half its volume, and doubled in salinity—threatening the survival of the nesting California Gull population, air quality with toxic dust storms, and this unique and critical ecosystem. Thanks to successful citizen advocacy and a set of rules governing DWP’s water exports, Mono Lake was saved from destruction.

Raising the lake to the mandated management level of 6,392 feet above sea level is critical to the lake’s ecological health, and the single most important metric for restoring Mono Lake. However, the lake is not rising on schedule.

Mono Lake is 6,383.2 feet above sea level as of July 1, 2025.

Management level

Mono Lake must rise to 6,392 feet above sea level, which is the management level set by the California State Water Resources Control Board’s Decision 1631 in 1994.

The management level was chosen for several reasons:

- reduce the lake’s salinity so that a healthy ecosystem can thrive

- improve air quality by covering much of the exposed dry lakebed, thereby reducing toxic dust storms

- protect California Gull nesting islets from on-shore predators with a substantial moat of water

- leave scenic tufa towers exposed around the shoreline

- to provide a buffer in order to protect these resources during lake level declines caused by dry years and droughts

As of July 1, 2025 Mono Lake is 8.8 feet below the management level.

RELATED RESOURCES: 2025 Lake level Forecast | Monthly Levels Since 1979 | Yearly Levels Since 1850

Mono Lake Level

| Level (feet above sea level) | Date/significance |

|---|---|

| 6428 | 1919 recent high stand |

| 6417 | 1941 pre-diversion level |

| 6392 | future management level |

| 6391.0 | target/trigger |

| 6385.1 | highest level reached since 1994 |

| 6384.1 | 7/1/2024 (1 year ago) |

| 6383.3 | 6/1/2025 (1 month ago) |

| 6383.2 | 7/1/2025 (recent) |

| 6380.0 | trigger: April 1st reduction |

| 6377.0 | trigger: minimum level |

| 6374.6 | 9/28/1994 (D1631 was issued) |

| 6372.0 | Lowest level (1/1/1982) |

Lake level export rules

In addition to setting the management level, the State Water Board also set water export rules for DWP that depend on Mono Lake’s level.

When Mono Lake is between 6,380 and 6,391 feet above sea level, DWP can export up to 16,000 acre-feet of water per year. If the lake drops to between 6,377 and 6,380 feet, DWP’s exports are reduced to a maximum of 4,500 acre-feet of water a year. And if Mono Lake is below or forecasted to be below 6,377 feet, DWP cannot export any water.

In the 2024 runoff year, DWP committed to exporting only 4,500 acre-feet of water to Los Angeles. This agreement was the result of a coalition of more than 25 Los Angeles-based conservation and environmental justice groups, led by the Mono Lake Committee, who asked LA Mayor Karen Bass to choose to not increase water diversions from the prior year. However, DWP abandoned that commitment when it quietly reversed its plan and began maximizing water exports. DWP ultimately exported 11,000 acre-feet of surface water by March 31, 2025.

Once Mono Lake rises to the target level of 6391 feet above sea level, a new set of rules will apply to DWP’s water exports.

Mono Lake is not rising on schedule

In 1994, the State Water Board designed a 20-year transition plan to raise Mono Lake to 6392 feet. But in 2014 the lake still had nearly 13 feet to rise, in part because of a severe drought. Even after allowing an extra seven years for Mono Lake to rise, it was still 10.2 vertical feet lower than the management level at the State Water Board’s next check-in, which was September 2020.

Mono Lake is far from recovering from decades of excessive water diversions. The Mono Lake Committee is monitoring and studying this closely, in preparation for a State Water Board hearing to consider modifying DWP’s water exports to ensure that the lake rises to the healthy management level.

About the above graph

DWP’s stream diversions caused Mono Lake to lose half its volume and fall more than 45 vertical feet, negatively affecting the Mono Lake ecosystem, millions of migratory and nesting birds, salinity, and air quality. Even after the State Water Board mandated that Mono Lake rise to the Public Trust lake level of 6,392 feet in order to achieve ecological sustainability, restore damaged resources, and minimize air quality violations, DWP’s stream diversions have continued to keep Mono Lake too low by exacerbating lake level drops during droughts and eroding lake level gains during wet years. Modeled by the Mono Lake Committee.

Why is Mono Lake rising more slowly than expected?

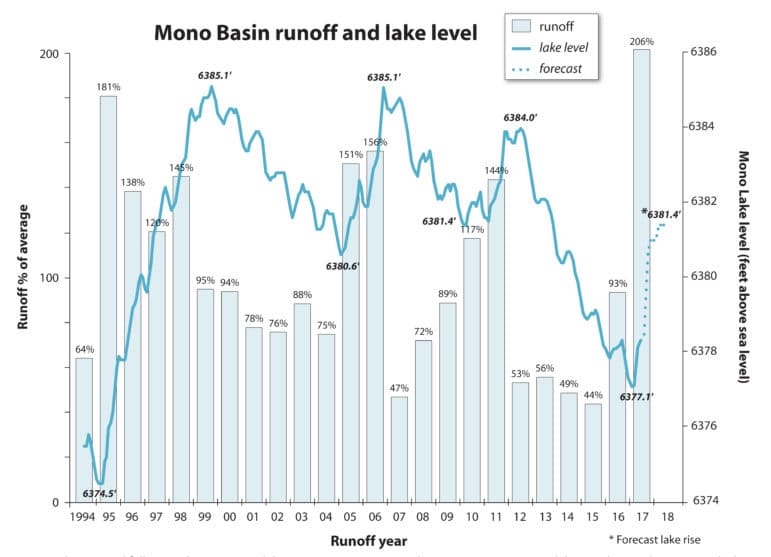

The State Water Board projected that Mono Lake would attain the 6,392-foot level in an average of 20 years, give or take a decade depending on drier or wetter conditions. Those expectations were based on a hydrological model of Mono Lake’s inflows and outflows that projected the lake’s rises and falls through time. As is standard practice, the model utilized hydrology and climate data from the preceding historical period.

How did the model assumptions hold up? With available data from the years since Decision 1631 (1995–2021) we can compare the historical 50-year (1940–1989) hydroclimate that was used in the model projections. Focusing on the four largest components of Mono Lake’s hydrology illustrates how less water was available to the lake than projected and the consequent impact on lake level.

Component 1: Sierra Nevada runoff

Mono Lake’s level depends mainly on snow that falls on the Sierra Nevada in winter and melts during warmer months. Despite the 2012–2016 drought, runoff from the Sierra has only decreased slightly—about 2% on average—between the historical (1940–1989) and recent (1995–2021) periods. But because Sierra runoff is the major inflow to Mono Lake, accounting for nearly three-quarters of incoming water, this small deficit adds up over time and can explain roughly two feet of Mono Lake’s “missing” water.

Component 2: Basin precipitation

Analysis of the precipitation east of the Sierra Nevada indicates a more marked decline. Precipitation at Cain Ranch, southwest of Mono Lake, has decreased 20% between the historical and recent periods, suggesting that snow and rain falling directly on Mono Lake and adjacent land may have significantly decreased. Ongoing analysis of weather stations throughout the region suggests a broader decreasing trend but conclusions remain preliminary. Basin precipitation contributes nearly 25% of lake inflows, so the precipitation decrease could account for a significant reduction in lake inflow and explain upwards of six feet of “missing” lake elevation.

Component 3: Evaporation

Lake evaporation is the primary outflow from Mono Lake. Unfortunately, estimating evaporation from saline Mono Lake is challenging, and long-term records are not available. Preliminary analysis of regional data suggests evaporation rates may have increased marginally between the historical and recent periods. If Mono Lake has experienced a similar increase in evaporation rates, modeled results would have underestimated cumulative evaporation outflow by up to 100,000 acre-feet or roughly two feet of lake elevation.

Component 4: DWP stream diversions

In addition to natural processes, the model incorporated DWP stream diversions and Grant Lake Reservoir operations into its Mono Lake level projections. The model assumed that DWP would be unable to divert all of the streamflow allowed in some years due to operational constraints. Since 1995, however, DWP has been able to fully divert all authorized exports each year. This difference accounts for more than a foot of “missing” lake elevation.

Over time, what may seem like relatively small changes in the main components of Mono Lake’s hydrology can add up to hundreds of thousands of acre-feet of water and can explain why the State Water Board expected that their management rules would result in a lake level higher than we see today.

Going forward, scientists predict more variable swings in weather, with periods of drought interspersed with very wet, snowy winters. As average temperatures rise, more precipitation is predicted to fall as rain instead of snow, and snow that does fall will melt earlier in the year.

As the effects of climate change continue to be better understood, we must factor them into our understanding of Mono Lake’s rise.

Reaching the management level

In 1994 the State Water Board acknowledged that its transition plan to raise the lake in about 20 years could be thrown off schedule by actual climate and hydrology in the years following the decision. They wisely put a date two decades later, in 2014, onto the calendar and said that if the lake had not risen as expected, they would hold a hearing to see if the water exports allocated to DWP might need adjusting to solve the problem.

In other words, the State Water Board’s lake protection requirement would not change over the years, but the rules for achieving it might.

The slower-than-expected lake rise scenario, unfortunately, has materialized. And the Board’s once-distant calendar date passed a decade ago. On that day, the lake stood 12 feet below the management level, and the Committee agreed to give the lake six more years to climb out of drought. Yet on the morning of September 28, 2020, the lake stood at 6,381.5 feet above sea level, still more than ten feet below the expectation we had back on the same day in 1994 when we watched the Board mandate a healthy lake level requirement.

The State Water Board’s lake protection requirement—raising Mono Lake to 6,392 feet above sea level—will not change. But the rules for achieving it might.

The timing of the hearing has not yet been set, but Committee preparation is well underway. Updating the lake level forecast model, for example, is essential to providing the analysis needed to consider new rule scenarios, and the Committee team has years of intensive work already complete.

DWP’s vast water diversions in the last century drove Mono Lake down 45 vertical feet and pushed the ecosystem to the edge of a cliff. But with concerned citizens raising the alarm, the State Water Board changed the outlook for Mono Lake and charted the path to a sustainable future that returns the lake and its birds and wildlife to health. All we have to do is follow that path. It is in everyone’s interest to step back from the brink by raising Mono Lake to the mandated healthy level.

Related Posts

Top photo by Robb Hirsch.