Mill Creek water was never exported to Los Angeles, but the creek has still suffered from excessive water diversions and ecological degradation akin to Mono Lake’s other tributary streams (see Mono Basin Streams).

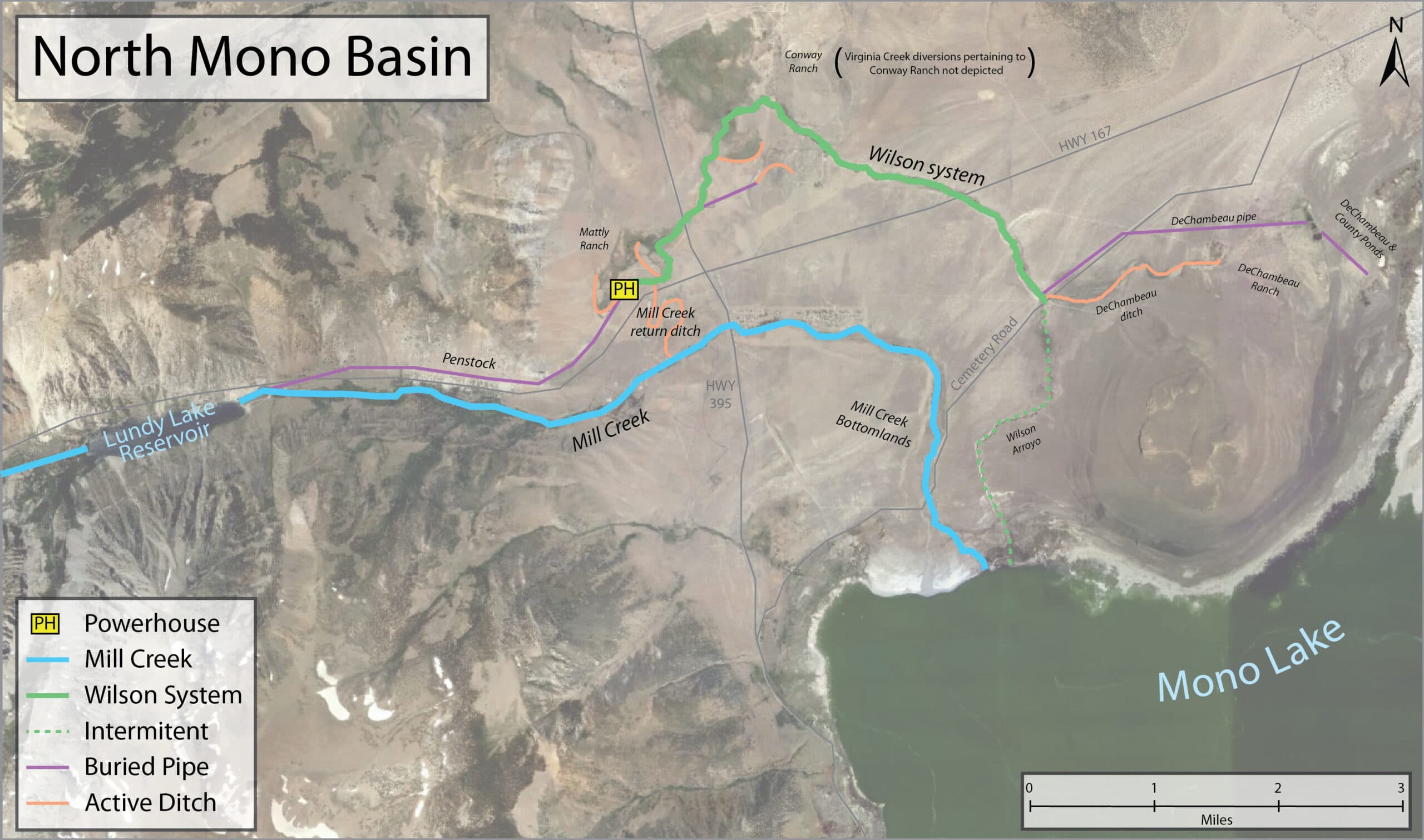

Water diversions from Mill were driven largely by hydropower infrastructure that routed water to generate electricity, but was unable to return the water to Mill Creek as legally required, sending it instead into an irrigation conveyance system known as the Wilson system. The Mono Lake Committee, in coordination with government agencies and other non-profit groups, has been working to make sure that water is delivered correctly to both Mill Creek and the Wilson system, in accordance with long-established water rights.

A critical resource threatened

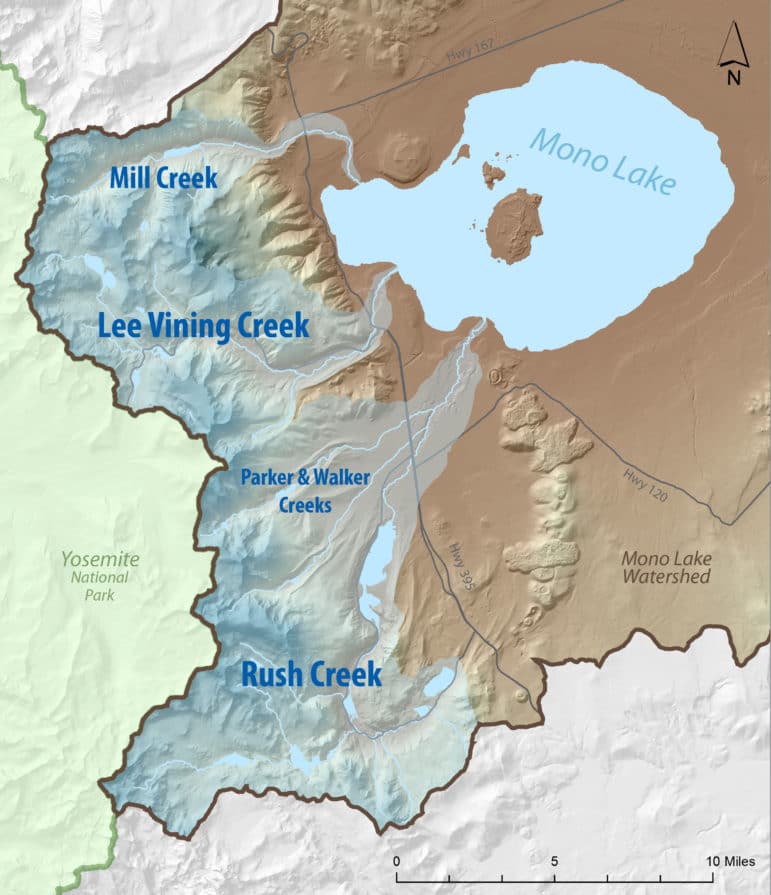

Mill Creek is the third largest stream in the Mono Basin, with headwaters in the Hoover Wilderness that flow down Lundy Canyon, through waterfalls, fields of wildflowers, beaver dams, Lundy Lake Reservoir, and rare wooded wetlands before forming a delta as it reaches Mono Lake.

Southern California Edison (SCE) operates the Lundy Lake Reservoir and connected hydropower facilities, which are designed to “borrow” Mill Creek water to generate electricity, but have struggled to return the water to Mill Creek in accordance with well-established water rights, due largely to infrastructure constraints. With inadequate infrastructure to return water back to Mill Creek, water has defaulted down the Wilson system, a collection of irrigation ditches and watercourses developed over the past century.

For over 40 years, more than 75% of Mill Creek’s flows have been diverted away from Mill Creek due to inadequate infrastructure, which means that Mill Creek has received less than half of the water it should lawfully receive according to the adjudicated water rights. These excessive diversions most significantly impacted the bottomlands of Mill Creek, where a once robust wooded wetland has been nearly wiped out.

Following the water rights

Through years of a Federal Energy Regulatory Commission relicensing process for the hydropower operation, the Mono Lake Committee, together with other stakeholders, has supported SCE’s efforts to improve the infrastructure needed to achieve the goal of accurate distribution of water as defined by the water rights.

Importantly, putting water back into Mill Creek is not happening at the expense of the Wilson system. The water rights allow for up to 40% of Mill Creek’s water to be delivered to water right holders through the Wilson system. So long as these water right holders request their water, there will be year-round water released into the Wilson system.

Progress underway

SCE has made huge strides in improving the water return infrastructure and has developed modeling tools for guiding the operations of their hydropower facility. As a result of this work, SCE has been successfully operating in accordance with the water rights since 2019.

While work still needs to be done to make sure these practices persist into the future, the ecological benefits are already being realized. On Mill Creek channels are reopening, vegetation is expanding throughout the bottomlands, and flows are persisting across the landscape. So while Mill Creek restoration may be on a different track than the other Mono Basin streams, we’re excited to see similar restoration results occurring.

There’s more to the story

There are lots of resources available to better understand the history and progress of Mill Creek restoration, but if you have a question, or would like more information, please contact Eastern Sierra Policy Director Bartshe Miller at (760) 647-6595.