A note on the spelling of the Tribe’s name

In October 2024 the Tribal Council formalized one official spelling for the Tribe’s name: Kootzaduka’a. The Mono Lake Committee had previously used the spelling “Kutzadika’a,” which was one accepted spelling, but will be using the official spelling from now on.

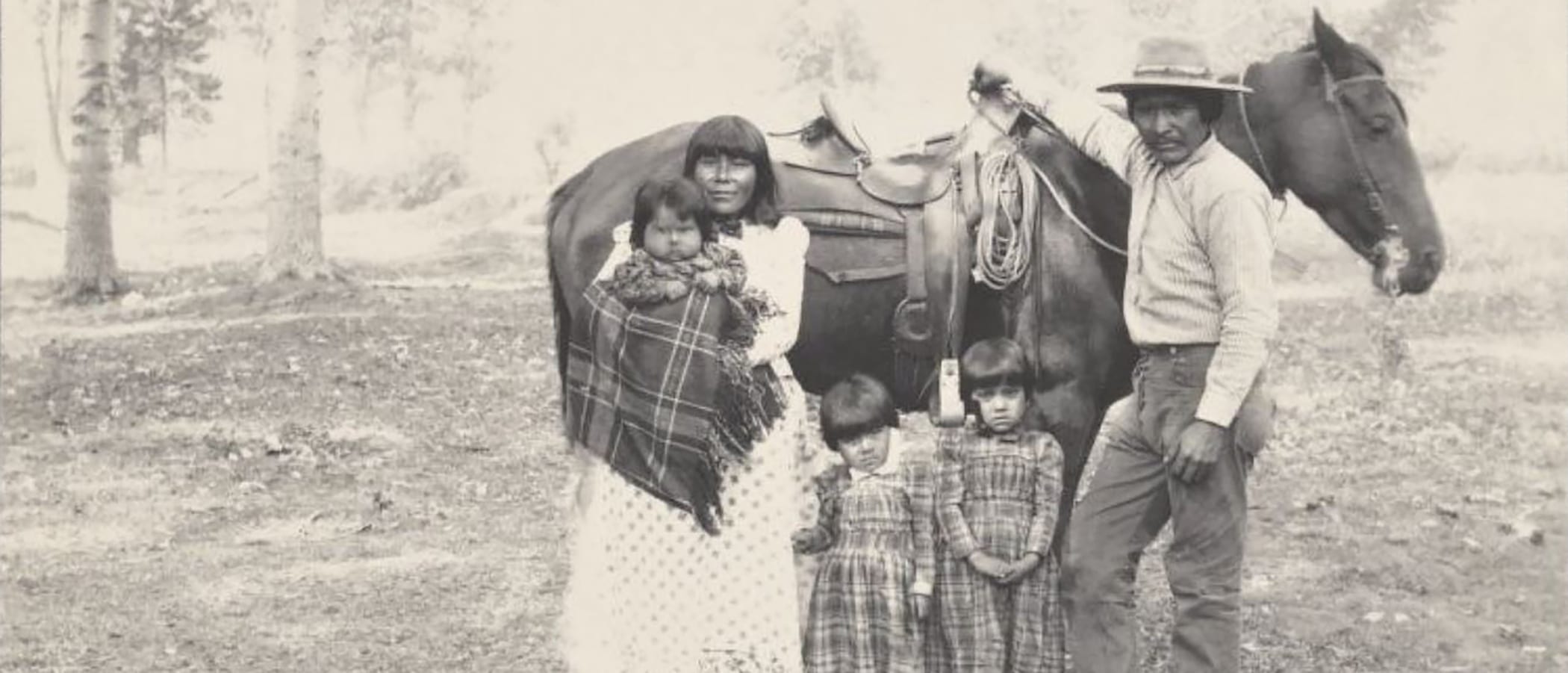

Mono Lake Kootzaduka’a Tribe

The Mono Lake Kootzaduka’a Tribe has resided in the Mono Lake–Yosemite region since time immemorial. They are the southernmost band of the Numu (Northern Paiute) and speak the local dialect of Numu Yadooana. The unique landscape of the Mono Basin has been nurtured by the Kootzaduka’a and in turn the land has been bountiful to them. To the unknowing eye, the Mono Basin can be perceived as a lifeless desert, but the Indigenous knowledge of the Kootzaduka’a Tribe proves this wrong.

The seasons influence the movement of the Kootzaduka’a throughout the Mono Basin and led to the establishment of trade routes in every direction, some of which are still used today. Stories passed along through time share what life in the Mono Basin was like before white settlers arrived. While the traditional Kootzaduka’a way of life was forever altered when European Americans arrived in the Mono Basin, the Tribe has preserved their culture and history. The resilience of the Kootzaduka’a is a reflection of their past and a hope for their future.

Circle of the seasons

Knowledge of the land and knowing when to hunt and harvest helped the Kootzaduka’a live in the Mono Basin for countless centuries. The following traditional knowledge is still alive and well today.

In the autumn the people would move to pinyon camps in the hills north or east of Mono Lake. Here they would camp and collect pinyon pine nuts, a highly nutritious food with a balance of fat, protein, and carbohydrates. Because of its fat content, the nut could be easily stored, providing a reliable food source throughout the winter months when food was scarce. The pinyon pine nut is regarded as one of the most important food sources for the Kootzaduka’a.

After the pinyon harvest, the people would go on rabbit drives, killing large numbers of jackrabbits and cottontails for food and skins, their principal clothing source. Long before the first white settlers arrived in the Mono Basin, the Kootzaduka’a would also hunt pronghorn antelope by driving them into corrals.

By winter the people moved east of Mono Lake to milder, lower-elevation valleys and relied on extensive food stores. By late spring the Kootzaduka’a returned to the Mono Basin, making camps along Rush Creek and other freshwater streams. From these locations the women would travel to the shores of Mono Lake to collect the pupae of the alkali fly, also known as kootzabe. Kootzabe is the namesake of the Kootzaduka’a Tribe.

Every other year in summer the Kootzaduka’a would collect piagi, or Pandora moth larvae, from the surrounding Jeffrey pine forest. In addition to these foods, the Kootzaduka’a gathered roots and berries, and countless other plants including blazing star, great basin rye, and goosefoot. Seasonal game in the mountains and nearby valleys and waterfowl along Mono Lake’s shores and freshwater streams were also important sources of food.

The Mono Basin did not provide abundant food year round, but it did provide enough food seasonally to sustain a population of nearly 200 individuals before the first European Americans arrived in 1852.

Trading and sharing

When climatic events resulted in less sustenance in the Mono Basin, or to add variety to Mono Basin food sources, the Kootzaduka’a traveled to neighboring Tribes to trade. Along with the food of the basin like salt and pinyon pine nuts, other trade items included basketry supplies and obsidian from the Mono Craters.

Each year, the Kootzaduka’a traveled well-worn trails to Yosemite through what is now called Bloody Canyon. In return for supplies from the Mono Basin, the Miwok in Yosemite Valley traded and shared acorn, berries, shell beads, and basketry materials. Routes into Yosemite established long ago are still traveled by members of the Tribe to uphold these traditional journeys.

A familiar story

Today there are still Kootzaduka’a living in the Mono Basin and the Eastern Sierra. They continue to be connected to their land, traditions, and community, but have had to survive through the trials that all Indigenous people have experienced.

The silver and gold boom in the mining towns of Aurora and Bodie led to an insatiable need for wood and other resources. When residents of those two towns cut the surrounding pinyon pine forest for firewood, it deprived the Kootzaduka’a of an important seasonal food source, pinyon pine nuts. Additionally, increasing settlement in the Mono Basin pushed the Kootzaduka’a from their prime camping and food gathering lands, which were typically close to fresh water and thus the most desirable land for ranching and agriculture.

Native people were forced to occupy marginal land from which they could no longer effectively hunt or gather food. In time the Kootzaduka’a had no choice but to work on surrounding ranches since they could no longer gather food reliably. Families moved to Mono Basin ranches and farms and worked for the new landowners in order to survive on the very land that was theirs.

Many tactics were used by non-natives to try to weaken the Kootzaduka’a Tribe’s culture. Across the United States “religious” practices and Native languages were outlawed until 1978. Boarding schools were used to separate young Native children from their Tribes and assimilate them into white culture. The arrival of the Los Angeles Department of Water & Power was also detrimental to the traditional Kootzaduka’a life. Land was taken and important hunting and foraging ecosystems were lost.

Kootzaduka’a today

Members of the Kootzaduka’a Tribe still live by Mono Lake and in surrounding areas. They have maintained traditional practices, including harvesting kutsavi and pinyon pine nuts as well as traveling the long-established trade routes. They are connected to the Mono Basin now and forever.

The Tribe has been working to achieve federal recognition since the mid-1970s. The most recent efforts included a bill that was introduced in September 2020, which expired once the 116th Congress ended. In May 2021 then-Representative Jay Obernolte introduced a similar bill to, which expired when the 117th Congress ended. In May 2023 current Representative Kevin Kiley sponsored a new, similar bill, though there has been no news or progress to move the bill forward. Receiving federal recognition would mean the Tribe would possess certain inherent rights of self-government and Tribal sovereignty, and would be entitled to receive certain federal benefits, services, and protections because of their special relationship with the United States. It would also mean that decades of work and centuries of resilience would be recognized.

Charlotte Lange, Tribal Chairperson, said, “The Mono Lake Kootzaduka’a Tribe has been enduring this process of recognition for decades. It saddens my heart to hear our elders say, ‘I won’t see it in my lifetime.’ My grandfather fought for the Tribe and his strength keeps my dedication to follow in his path.” In a conversation with her, she plainly stated, “We just want to come home.”

Note: The information on this page has been researched and summarized from various sources by Mono Lake Committee staff.

Efforts to achieve federal recognition

The Kootzaduka’a Tribe has been seeking federal recognition for many years, but so far legislators who have introduced bills for federal recognition have not been successful in moving them forward. See our blog for the Mono Lake Committee’s coverage of federal recognition efforts. Go here to sign a petition to support federal recognition.

Please visit the official Mono Lake Kootzaduka’a Tribe website for more information.

Learn More

Top photo courtesy of the Mono Lake Kootzaduka’a Tribe.