Mono Lake receives the vast majority of its water from Sierra Nevada snowpack in the form of snowmelt by way of five main streams.

Under natural conditions, these streams flow at stable low flows in the winter and begin to swell and surge during the spring and summer months with the melting of winter’s snowpack. In recent history, all five of these streams have experienced excessive water diversions, which has had a negative impact on the ecological health of the streams as well as Mono Lake. Today, efforts continue to make sure that these streams receive the water needed to restore and revitalize ecosystem health and function.

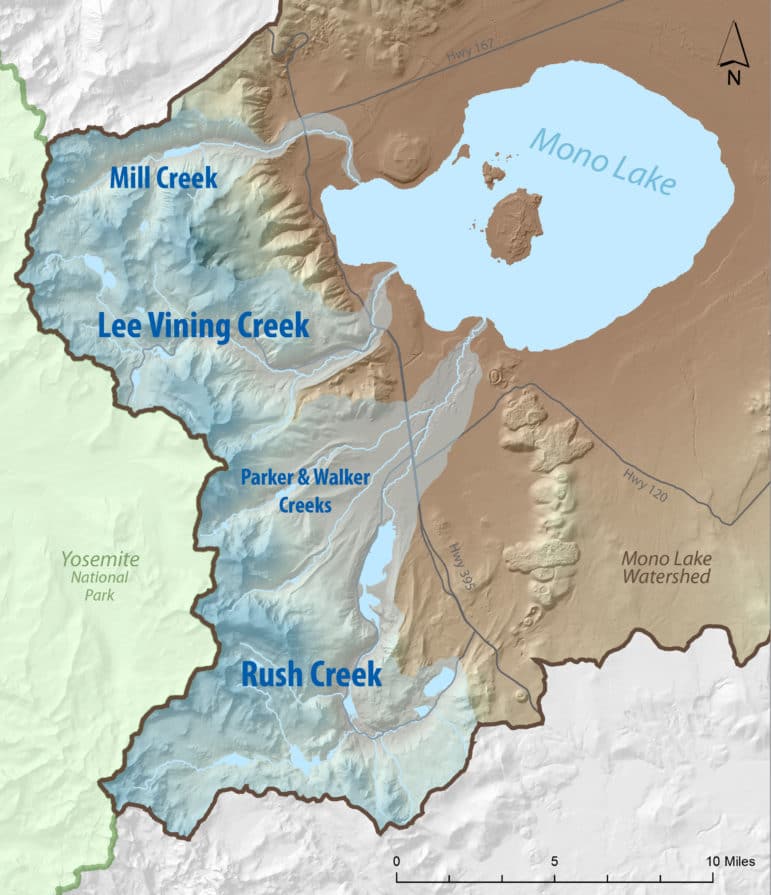

Mono Lake’s five main tributary streams

Rush Creek and Lee Vining Creek are by far the two largest sources of water for Mono Lake, delivering roughly three-quarters of the total basin-wide surface flow to Mono Lake. Mill Creek is the third largest stream and exceeds the total combined flows of Parker Creek and Walker Creek, the fourth and fifth largest streams in the Mono Basin.

All five creeks are incredibly diverse and valuable ecosystems. With headwaters in alpine and sub-alpine environments, the streams flow through mixed conifer and pinyon-juniper woodlands at lower elevations, and their channels fan out into multiple streamlets that form expansive riparian and meadow habitats in bottomland reaches, all before reaching Mono Lake’s shores where they create critical delta habitat. Since much of the area surrounding Mono Lake is arid sagebrush scrub habitat, these streams are truly desert oases for a large variety of mammals, birds, fish, reptiles, amphibians, and arthropods.

Excessive water diversions

Starting in 1941, Los Angeles Department of Water & Power (DWP) began to export water from Mono Lake’s tributary streams to the City of Los Angeles via the Los Angeles Aqueduct. By 1950, Rush, Lee Vining, Parker, and Walker creeks received little to no water below DWP’s diversion dams, which led to massive die-offs of large cottonwoods and willows as well as the destruction of the trout fishery. Extreme flooding events did deliver water to these dry streambeds in the late 1960s and early 1980s, but without vegetation to hold the streambanks in place, these floods caused a lot of damage to the physical structure of the streambeds. These flooding events were particularly destructive for Rush and Lee Vining creeks.

What about Mill Creek?

Mill Creek is the only one of Mono Lake’s five main tributary streams that was not diverted to the City of Los Angeles. However, it too has a history of excessive diversions. Find out what makes Mill Creek different and how the Mono Lake Committee is working to restore flows to the third largest stream in the Mono Basin.

Capacity for self-renewal

After decades of litigation with DWP over the need to save Mono Lake, the California State Water Resources Control Board set a management lake level for Mono Lake along with a goal to restore the four streams damaged by DWP’s water exports (Rush, Lee Vining, Parker, and Walker creeks) to pre-diversion conditions. These conditions required that streamflows would resume in historic channels and support both a healthy trout fishery as well as robust riparian and meadow habitats. But how exactly this would be achieved and how exactly this would be measured required extensive scientific analysis, discussion, and planning.

It was clear that enough damage had occurred to these streams that conventional physical restoration work had to be done to get the restoration process going on the right track–opening blocked channels, planting trees, and reintroducing trout. But rather than have a singular criteria of a healthy stream ecosystem as a way to track restoration progress, the State Water Board appointed Stream Scientists have worked to understand, quantify, and reproduce the ecological processes that create and maintain a healthy stream ecosystem.

Since the 1994 Water Board decision the streams have been on a path to healing. Stable winter and fall flows sustain the trout fishery and keep the ground charged with water, established willows, cottonwoods, and pines have stabilized stream banks, spring and summer floods spread across floodplains and germinate seedlings, all of which are natural processes that allow for the system to drive its own restoration.

“Land health is the capacity for self-renewal.”

-Aldo Leopold

Much work is still being done to make sure that the critical ecological processes identified by the Stream Scientists are backed with science, and supported with policy and restoration action, as the Mono Lake Committee works to make sure these streams are able to heal and flourish.

There’s more to the story

Whether you’re interested in environmental policy, stream restoration, or the science behind it all, there are lots of resources available to explore these concepts in greater detail.

related resources: Historic conditions of Mono Basin Creeks | Stream Restoration agreement | State Water Board Decision|Mono Basin Compliance Reporting to SWRCB by LADWP

Learn More

Top photo by Rick Kattelmann.