This post was written by Sara Matthews, 2015 & 2016 Mono Lake Intern.

For the past 20 years the saga of the Osprey has been unfolding at Mono Lake. In the mid-1980s the first nesting pair of Osprey was recorded at Mono Lake. They built their nest of assorted sticks and branches high atop a tufa tower rising up out of Mono Lake’s salty, alkaline waters. Unfortunately, that year was unsuccessful for the pair and they eventually left the nest in the fall with no signs of chicks ever having hatched. Determined, the pair returned to Mono Lake the next year and began the process again—and again, they were unsuccessful. All told, it took the pair of Osprey five seasons of returning to Mono Lake and giving their best efforts before they successfully hatched two chicks. Since then, Mono Lake’s Osprey population has been on the rise.

Some might think that Mono Lake, with its fishless waters, would be an unlikely nesting ground for a species of raptor that subsists almost entirely on fish. However, the protection that the water affords the nesting sites from ground-dwelling predators has proven to make the extra effort needed to find food worth it. Although there have been year-to-year fluctuations in the number of Osprey nesting at Mono Lake, overall there is an increasing trend. This year, 12 nesting pairs of Osprey have made their summer home here.

These beautiful birds of prey have become a crowd favorite at Mono Lake, drawing many a visitor’s gaze from the shore of the lake as they soar by on their way to the nesting ground. With an average wingspan of over five feet, razor-sharp talons, and distinctive black and white “robber’s mask” markings, it’s no wonder why. These dramatic birds have an air of mystery to them, also catching the eye of the scientific community. Although Osprey are among the most well-studied of North American raptors, there is still much to learn. Where do they go when they leave Mono Lake? How far do they travel while they’re staying at the lake? What is the limiting factor in their decision to nest in one place and not another?

Lisa Fields, an Environmental Scientist with California State Parks, has been studying the Osprey at Mono Lake to find out the answers to these questions and more. Since 2004 the Osprey Research Program has sought to monitor this unique nesting population of osprey. In the early years, funding only allowed for nest monitoring; however, by 2009 the program expanded to include banding the birds. Although data collected from banding is somewhat sparse (it shows where the bird is when it is banded and where it is when it dies) it has provided some insight into the birds’ movements. For example, a Mono Lake Osprey was found thousands of miles to the south, near Corpus Cristi, Texas.

Recently, increased funding has allowed for new technology to be brought to the Osprey research at Mono Lake. Satellite telemetry allows researchers to track the movement of an animal by using orbiting satellites that detect signals emitted from a transmitter attached to the animal. The transmitter allows for a much more intimate look into the daily movements of the Osprey. In 2013, the first Osprey at Mono Lake was equipped with a transmitter. Though the data collected from that year was useful, because the Osprey was female, much of the nesting season bore little movement to be tracked—typically, the female Osprey remains on the nest until the young fledge, while the male Osprey hunts for food and brings it back to the female, which allows for maximum protection for the young. However, come September she was tracked migrating over the desert to near Mazatlán, Mexico. This year, a male Osprey named “Leroy” was chosen and on June 18 he received his transmitter.

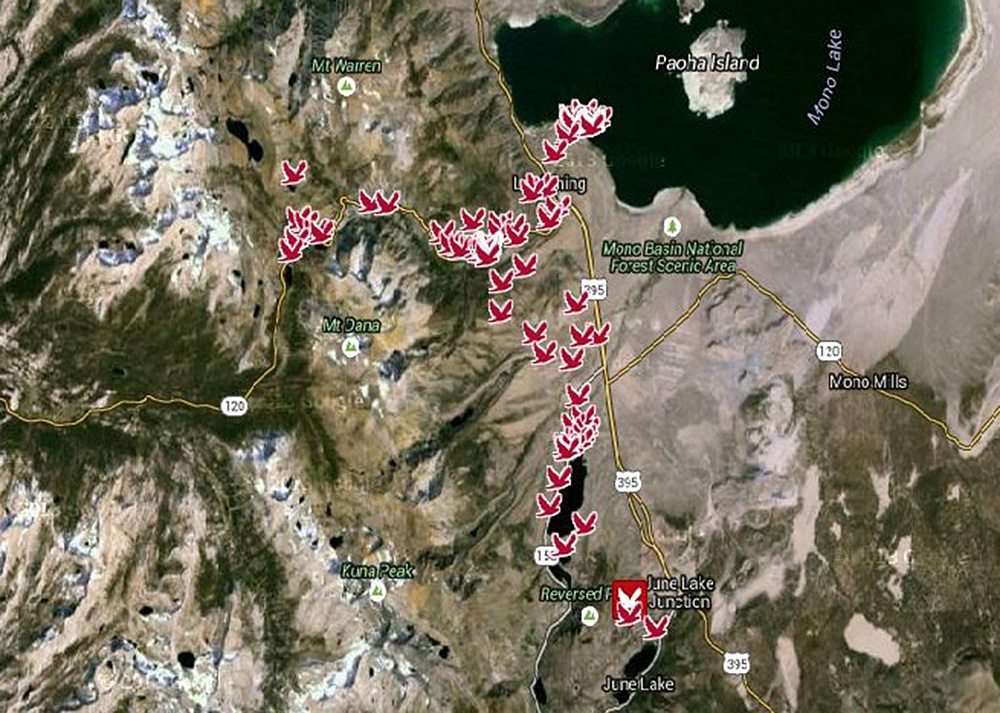

Since then, the data has been pouring in. Data received from Leroy has already given much insight into the daily routine of the birds. Leroy has been tracked going far up Mono Lake’s tributary streams to find fish. So far, he has been shown to fly as far as Tioga Lake (up Lee Vining Creek along Highway 120), Grant and June lakes (along the June Lake Loop, Highway 158). These observations are exciting because they provide insight into the local movements of Osprey and will eventually contribute to a much better understanding of the behavior of these magnificent birds.

If you’re looking to catch a glimpse of Leroy and his brood at the lake this year, you’ll have to come visit soon! Across Mono Lake, this year’s fledglings are getting ready to test their wings. Leroy and his mate will stick around to provide food to the fledglings as they learn to fly and hunt on their own, but once the fledglings are fully independent the entire family will go their separate directions on their southward migration to the wintering grounds. Where exactly they go along the way is yet another puzzle that Leroy and his transmitter will help to solve.

The Osprey Research Program at Mono Lake is funded by Friends of Mono Lake Reserve, the Mono Basin Bird Chautauqua, California State Parks, and the Eastern Sierra chapter and Central Sierra chapter of the Audubon Society. If you’re interested in helping to unravel the mysteries of Leroy and the rest of the Mono Lake Osprey, you can donate to “Osprey research” through the Friends of Mono Lake Reserve!

I’ve had the pleasure of watching – and photographing osprey at the lake for a couple years.

I find the research of their travels fascinating! I didn’t realize the extent of their migratory wanderings. (Then again, I shouldn’t be surprised, considering some of the other lake visitors pausing on their southward journeys.)

It’s amazing that one determined pair can have such a positive impact on a threatened population. I’ve seen them flying high over Twin Lakes.

I’m glad to know about Leroy’s flights to get food. I’ve photographed them for a number of years at Community Park and South Tufa and wondered about their sources for prey. I’ll look forward to future tracking.

thank you

On 8-25, while camped at Evelyn Lake (near Vogelsang camp in Yosemite) we saw an osprey with fish being chased by Prairie falcon. Osprey eventually dropped the fish and they both flew away.

Mono Lake is for the birds! The lake is its birds…the birds are the lake. I am so very grateful for David’s and Sally’s vision. I am proud to be a charter member of the MLC.

Perhaps some of these Osprey will migrate to San Diego. I have seen a few over the years. Good story and a successful story for the Ospreys.

How delightful to read the above account of Mono Lake’s osprey. Living in Salem, OR, I rarely see Mono Lake, but yearly see, daily from our south facing patio the North River Road Park resident osprey. Most interesting to observe parents training those/that offspring for ultimate departure. While walking in the park one day even had an opportunity to introduce a visitor to this community and neighborhood to the circling and landing osprey which he, the visitor, was feeling excited to be viewing what he was positive was an eagle. Though unknown to him, that osprey then became an object of focus for his “rather fancy” camera. Many years we see the nest nearly demolished by our winds and rain. Those birds are persistent, good builders and very good providers from primarily the Willamette River in this location.