Note: This post is the transcript of the Mono Lake Committee’s presentation for the State Water Board’s Mono Lake workshop on February 15, 2023. Executive Director Geoffrey McQuilkin gave the slide presentation, which we have adapted here for the website. You can watch a recording of this presentation here and see the entire workshop here.

In December the Mono Lake Committee asked the State Water Board to take emergency action to deliver more water to Mono Lake due to the lake’s perilously low level. We were specifically concerned about the increasing risk of coyotes accessing the islands in Mono Lake where California gulls nest.

As it turns out, Mother Nature took immediate action, surprising us all with six weeks of memorably wet weather in December and January. The wet winter means the lake will rise this year, and we recognize changed circumstances reduce the need for action before April 1.

At the same time, we have all seen this movie before.

After the wet winter of 2017 the lake rose multiple feet, but the Los Angeles Department of Water & Power (DWP) continued its water diversions and those gains in lake level were lost in subsequent years, returning us to the crisis we are here to discuss.

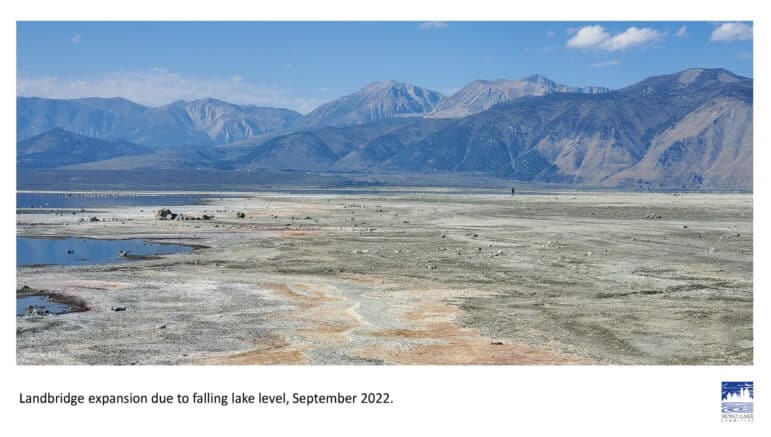

Today the lake surface elevation remains below 6380 feet, and melting snow won’t significantly affect lake level until summer. Thus, work is proceeding to install the temporary electric fence across the landbridge necessary to protect the gull colony.

Building fences on exposed lakebed highlights that, after 30 years, the protections established in Decision 1631 have not been delivered. To make sure we’re not back in this same position next spring, or the spring after that, action is necessary.

Mono Lake is a saline lake twice the size of San Francisco that supports a unique and highly productive ecosystem. The lake’s brine shrimp and alkali flies serve as an essential food source for millions of migratory and nesting birds, making it a critical stop on the Pacific Flyway.

The lake’s mysterious tufa towers and scenic qualities draw visitors from across the world, benefiting the local economy and Mono County community. The lake has a long resume of recognitions of its significance including that it is a California State reserve, surrounded by a Congressionally designated Scenic Area, and is one of only two Outstanding National Resource Waters (ONRW) in California; the other is Lake Tahoe.

In the early 1940s, DWP began diverting Mono Lake’s tributary streams and exporting that water to Los Angeles. Deprived of inflow, the lake shrank in size. By 1982 it was half as big and twice as salty, its unique ecosystem was on the verge of collapse, exposed lakebed was polluting the air with dust, and coyotes were able to walk out to once-safe gull nesting islands. These diversions also severely impacted the cultural resources of the Kootzaduka’a Tribe, and I appreciate the Tribe will be presenting today and that the Board is taking seriously its racial equity policies. From the Committee’s perspective, the Tribe must be meaningfully involved in Mono Lake proceedings and hearings going forward.

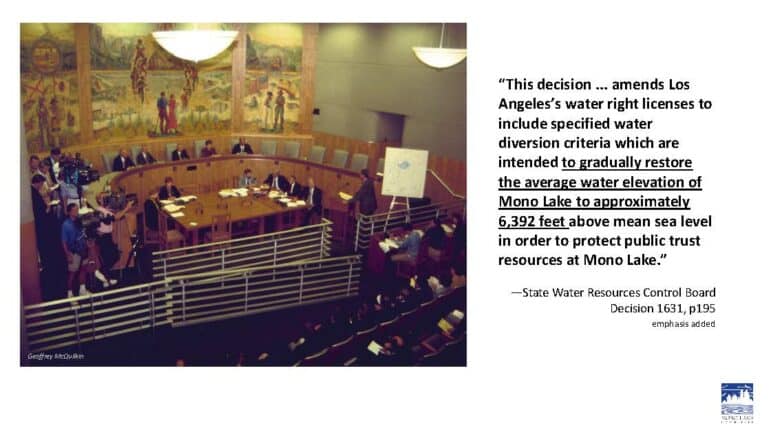

As Board staff just explained, in 1994, the State Water Board issued Decision 1631 (D1631) to stop this damage and restore the lake to health. The central requirement is to raise Mono Lake to a surface elevation of 6392 feet above sea level as a nature-based solution to protect a broad array of public trust resources. The decision reduced excessive DWP diversions to put more water into the lake and allow it to rise.

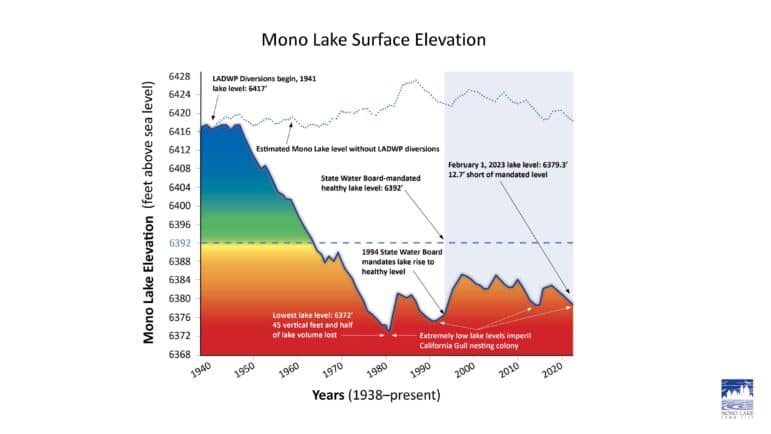

Let’s look closer at this history with this graph [above] of the level of Mono Lake over the past 85 years. There’s a lot here so let me highlight several things. First, at the left, you can see the precipitous decline in lake level once water exports began in 1941. As of now, in total, DWP has diverted 3,600,000 acre-feet of flow from the streams and 500,000 acre-feet of groundwater.

Now note the dotted line showing the level of the lake if there had been no diversions. The lake would have maintained its naturally fluctuating pre-diversion level even through climate change whiplash between wet and dry extremes, and the recent droughts.

Let’s look at the shaded right-hand portion of the graph showing the 30 years since D1631. The lake shows an initial rapid rise toward the 6392 foot protection level, shown as a dashed line. But then the lake stops progressing. Gains in wet years are not retained. In the past decade, the lake has fluctuated around the 6380 level. This is a clear illustration of the problem: with DWP continuing to maximize allowed diversions, the lake is not rising to 6392.

So in 1994, what did the Board expect D1631 would make happen?

The Board expected that the lake would rise to the 6392 healthy level … in a “reasonable” amount time of about twenty years … with limited stream diversions compatible with the plan for raising the lake, in order to provide water to Los Angeles.

So, has this package of expectations been met?

No, they have not.

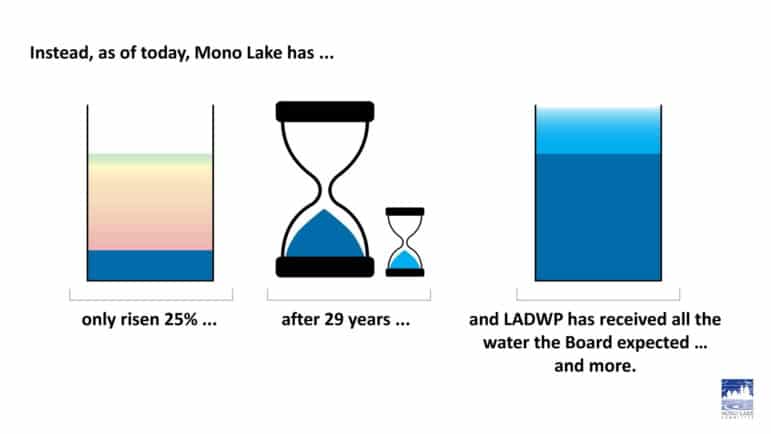

Today, Mono Lake has only risen 25% of the way to the healthy level. Twenty nine years have gone by, including the expected 20 years, a six-year extension, and even more years after that.

In contrast, for water diversions, DWP has maximized its allowed stream diversions every year since 1994, including the wettest years, when alternative sources were abundant. As a result, it has diverted all the water that D1631 expected—and more.

We are here today because the Board’s expectations for how D1631 would protect the lake have not been fulfilled. DWP has received all the water it was allotted, while Mono Lake has come up short.

Because the lake remains low, the problems of the past are the problems of the present. The time is now to put the lake onto a rising trajectory and achieve the protections promised by D1631.

I want to address some apparent confusion about one of the symptoms of the low lake level: and that’s the landbridge. DWP in its January letter asserts that “there is no landbridge” at Mono Lake, defying the existence of the 500-acre landscape feature I can see out the window.

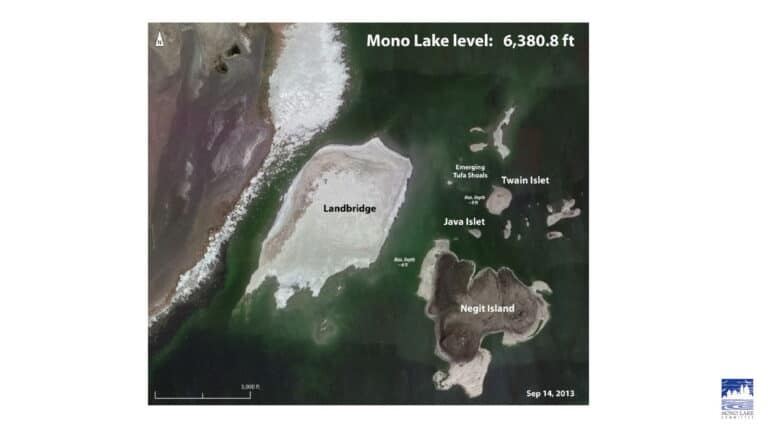

It is the large light colored area of land in the center of this image (below) taken at a lake level of 6383 feet above sea level (that’s about four feet higher than today).

The landbridge is the large swath of lakebed that was exposed as Mono Lake fell due to water diversions. The landbridge is located between Black Point and the north shore, and Negit Island. The California Gull nesting islet of Twain and others are visible on the right.

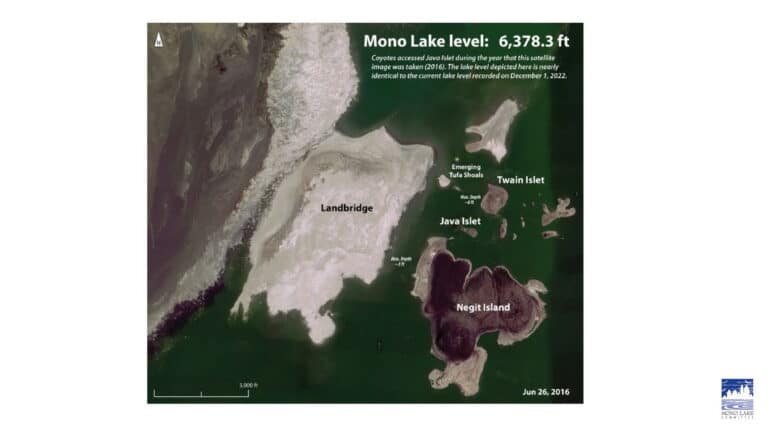

As the lake falls, the landbridge increases in size. Here, at lake level 6381, the landbridge has grown to about 350 acres and forms a full connection to the shore.

Evidence indicates a high risk of predators using the landbridge to reach the nesting islands when the lake surface is below 6380. At very low levels, like 6375, predators can walk across the landbridge with dry feet. At last December’s lake level of 6378.3 feet, shown here, predators can walk the landbridge to access the islands and wade or swim across shallow water at its southeast edge.

The flat landbridge edges change in size significantly in response to small lake level variations. A one inch lake level gain, for example, increases island separation from the landbridge by 30 feet or more.

~~~~~~~~~~

At this point in the presentation Geoff brought in Ryan Burnett, lead Gull Research Biologist for Point Blue Conservation Science to talk about the significance of Mono Lake and the nesting islands for California Gulls. You can see Ryan’s presentation here starting at 41:45.

~~~~~~~~~~

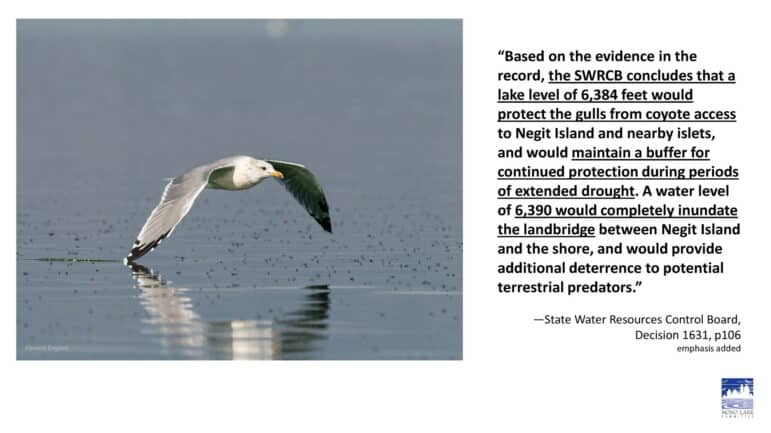

To wrap up the discussion about the risk of predators disrupting the nesting gulls, it is important to remember that the State Water Board studied this issue, evaluated the risks, and has already concluded that Mono Lake needs to be at or above 6384 to protect the nesting gulls specifically.

So, what is the Committee asking for today? The wet winter will raise the lake a couple of feet this year, so we are focused on what happens next. We all know dry years lie ahead, and six wet weeks is not a management plan, nor a remedy to 80 years of DWP water diversion impacts.

The Board must act to preserve the lake level gains of this—and any future—wet year. Suspending diversions until the lake rises to a healthy level will accomplish this. DWP will be able to resume diversions after the lake rises, and along the way will continue to benefit from its export of Mono Basin groundwater.

So, we are asking the Board to hold the hearing required by D1631 to change the diversion rules this year. Given the narrow scope of such a hearing, we believe the Board has access to the data and established hydrologic models it needs to proceed, and that participants could be ready to present proposed changes and evidence within six months. We ask the Board to implement stream diversion suspension before April 1, 2024, when DWP will otherwise likely quadruple the amount it diverts.

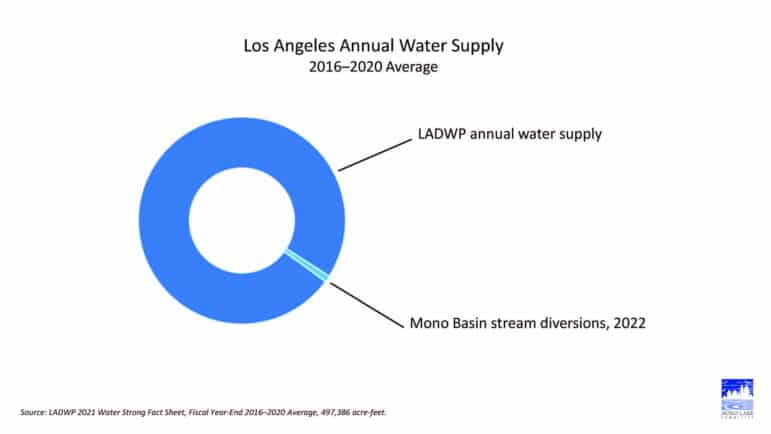

We don’t make this request lightly. We understand DWP is concerned about a change to the status quo, even though the 4,500 acre-feet of water in question this year is less than a percent of the City’s annual supply. We understand that the Board is busy. But this is an emergency for Mono Lake, which by this Board’s own determination must be a dozen feet higher than it is today to protect public trust resources.

DWP has many water sources in its portfolio and Los Angeles leaders have made significant commitments to rapidly implementing environmentally responsible local supply projects such as stormwater capture, turf replacement, conservation, and water recycling. Mono Lake has only Mono Basin precipitation for supply.

We are confident that Los Angeles can offset additional water the Board requires to flow to Mono Lake with sustainable local sources. In the past, tens of millions of dollars of state and federal funding have gone to DWP for this purpose. That’s why, over the past year, the Committee has repeatedly asked DWP to work with us again to secure more local supply funding for Los Angeles. One great potential project inspired by past successes is direct install water conservation programs focused on low-income communities, where water savings and monthly bill savings are joint benefits.

So far, DWP has refused to join us, but we understand an application from Los Angeles exists for over $100 million in state funding and we are confident it can help Los Angeles help Mono Lake.

In conclusion, let me share that I was fortunate to be in the state capitol in 1994 to witness the Board’s unanimous vote to adopt Decision 1631. It was a momentous day. The Board received a rare standing ovation from the crowded audience.

It was said in 1994 that the Decision would save Mono Lake. That promise is still in the words of the document. Now it is time to show that words have meaning, to show that California’s landmark commitment to Mono Lake and the public trust is real. The current low lake crisis shows us that quick Board action is needed to put the lake back on the rise, to fulfill the expectations of the Mono Lake Decision, and to turn those words into water to save Mono Lake.

Thank you for your time today for this important discussion.

Top photo courtesy of Lloyd Baggs.