The Mono Lake Committee has completed an innovative Stream Restoration Agreement with the Los Angeles Department of Water & Power (DWP) that promises a healthy future for 19 miles of Rush, Lee Vining, Parker and Walker creeks and certainty about the restoration of their fisheries, streamside forests, birds, and wildlife.

After three years of collaborative discussion, negotiation, and principled advocacy, the Committee is thrilled to have arrived at an agreement that just weeks before seemed out of reach.

The Agreement, negotiated jointly with California Trout and the California Department of Fish & Wildlife (DFW), implements a comprehensive plan for streamflow delivery, monitoring, and adaptive management built on extensive scientific stream studies over the past 15 years. In short, the Agreement will make the most of the water allocated to the creeks and lake under Los Angeles’ Mono Basin water licenses.

Natural streamflow patterns will be mimicked to rebuild the health of the streams and fisheries. Rush Creek’s valuable and rare bottomlands forest and channel habitat will be restored. Walker and Parker creek flows will benefit trout all the way to the lake’s edge. Lee Vining Creek flows will be optimized for fish and habitat.

Under the Agreement, collaborative operational planning will assure reliable Mono Basin operations to achieve both restoration and water export. Costs will be shared and compliance will be simplified. Additionally, scientific monitoring and adaptive management, directed by independent scientists, will assure that recovery is achieved.

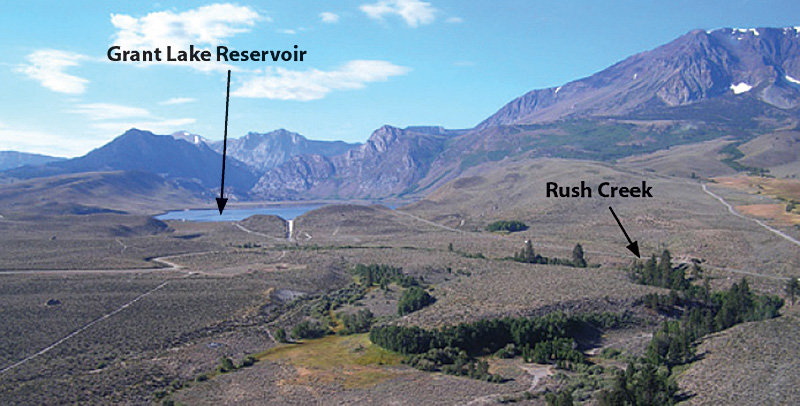

A key element of the Agreement is DWP’s commitment to invest an estimated $15 million to modernize antiquated aqueduct infrastructure at Grant Lake Reservoir Dam by building a new Grant Outlet structure. This will give DWP the capacity to actually deliver the required streamflows to Rush Creek. The new outlet will physically and symbolically show that the Los Angeles Aqueduct can achieve two goals: to deliver water to the people of LA and to protect and restore Mono Lake and the Mono Basin streams providing that water.

The Agreement was submitted to the State Water Resources Control Board just before their September 30 deadline. After review, the State Water Board will issue new legal water rights licenses to DWP containing, we hope, all the new streamflow requirements and associated provisions. State Water Board action could happen as soon as the end of the year.

The Agreement is the culmination of three years of intensive work by Committee staff, experts, and legal team in collaborative discussions and negotiations with DWP, CalTrout, and DFW. This major achievement owes thanks to many dedicated Mono Lake Committee members, friends, and supporters.

A new, exciting phase in stream restoration lies ahead. The Committee is already laying plans for speedy implementation of the Agreement with the goal of successful restoration of Mono Lake’s tributary streams.

Highlights of the Stream Restoration Agreement

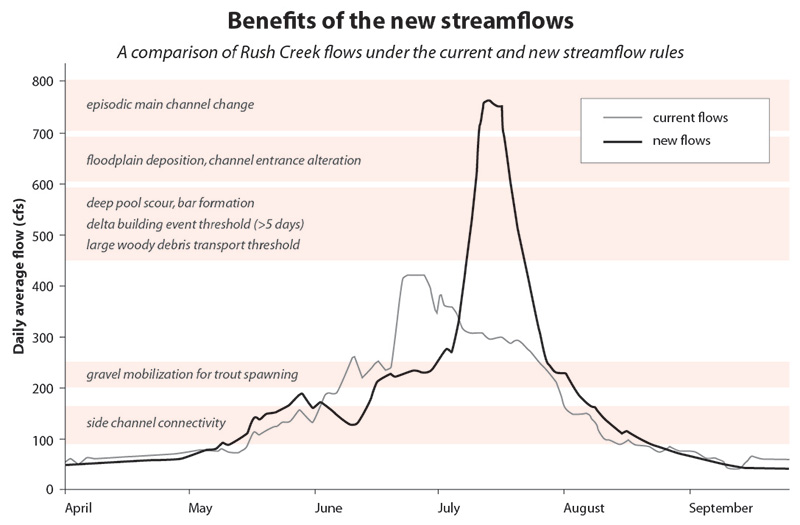

The Agreement fully implements the Stream Ecosystem Flows (SEFs) presented in the mandated 2010 Synthesis Report. In 1998 the State Water Board ordered intensive study by designated Stream Scientists that resulted in the development of specific day-by-day, stream-by-stream flow regimes. The SEFs mimic natural runoff patterns and activate the natural processes that will restore the streams. The implementation of SEFs is the single most important action necessary for stream restoration, and the Committee expects a significant leap forward in the streams’ recovery.

DWP will modify Grant Dam by constructing an outlet that reliably delivers flows to Rush Creek. Peak flows as outlined in the Synthesis Report are currently impossible to deliver due to the aqueduct’s World War II-era infrastructure, more specifically due to the lack of an adequate outlet facility. DWP will complete outlet construction and begin operation within four years of State Water Board approval. In order to offset the cost of the Grant Outlet, DWP will be allowed to export an additional 12,000 acre-feet of water from the Mono Basin if timely construction progress is achieved. This one-time allowance will defray approximately half of the cost of the outlet without changing the timeframe in which Mono Lake reaches its mandated management level.

The Agreement lays out how the fishery, stream, waterfowl, and Mono Lake monitoring work required by the State Water Board will proceed in coming years. Stream monitoring tasks, consistent with the 2010 Synthesis Report, are specified and thus initiate a new phase of stream monitoring. Mono Lake limnology monitoring, a source of dispute in recent years (see Summer 2012 Mono Lake Newsletter), will continue and is assigned to the expert scientists who have run the program for decades.

The Agreement provides for adaptive management in order to apply the knowledge learned through scientific monitoring for better stream recovery. Flexibility is provided to adjust the timing, duration, and magnitude of the Stream Ecosystem Flows to maximize their ecological benefit. Limitations assure that adjustments will not violate established minimum flows or reduce water exports to Los Angeles.

The Agreement requests deferral of the scheduled State Water Board hearing on DWP’s water licenses from 2014 to 2020. This will allow the Grant Outlet to be constructed and SEFs to be implemented without getting caught up in new legal proceedings.

The Agreement creates a new oversight team to reliably manage annual budgeting and contracting. The team is made up of DWP, the Mono Lake Committee, DFW, and CalTrout. DWP will fund a comprehensive list of monitoring tasks—and several previously-ordered restoration actions—at specified levels and the team will assure efficient implementation.

A collaborative approach is specified in the settlement for multi-year and annual Mono Basin aqueduct operations planning. This assures that expertise from all parties is used to develop the most successful plans possible. Operating the aqueduct to achieve both stream restoration and water export goals will take careful planning and coordination and the Mono Lake Committee will play an active role.

Translating numbers into nature

Leaf through the pages of the Stream Restoration Agreement and you can’t help but notice page after page of tables full of streamflow specifications—creek by creek, numbers for spring snowmelt floods, for winter baseflows, for spring seeding, for every type of wet and dry year the Mono Basin experiences.

These streamflow tables are at the heart of the scientific plan for stream restoration and central to the Agreement. But how do these numbers actually connect to stream restoration on the ground?

The scientists who developed them followed a methodical process. The starting point was to identify the natural stream processes that, once put into motion, will restore healthy stream habitat and conditions or trout. Flooding, floodplain seeding, channel shaping, pool scouring, gravel movement, groundwater recharge, and temperature maintenance are all good examples.

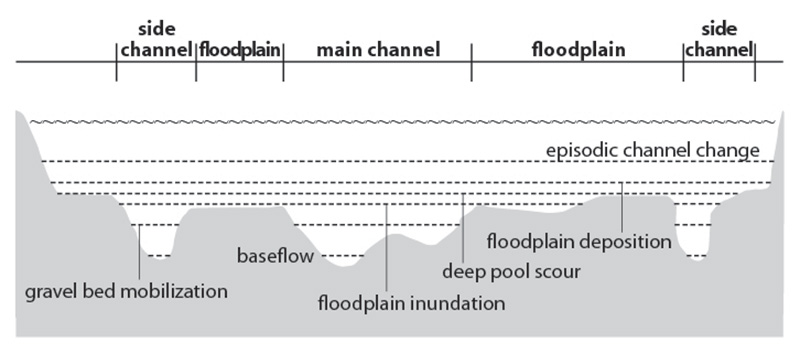

The scientists then determined the volume and timing of water needed in the streams to activate the processes. Larger volumes with greater energy—typically associated with the springtime melt of the Sierra snowpack—are necessary to activate some of the critical channel shaping processes. Figure 1 shows a simplified creek cross section, illustrating how higher flows raise the height of the creek and activate different natural processes.

For example, for a streamside cottonwood-willow forest to thrive, springtime floods that spill over stream banks are needed; these floods deposit sediment and allow seeds to germinate across the floodplain. Actual physical measurements of water depths—or stage heights—in the channels of Rush Creek were taken in multiple locations, field observations were made, and as a result, floodplain deposition events could be directly correlated to specific streamflows.

As another example, to scour the deep pools favored by trout, the rate of flow needs to be high enough to have the energy necessary to move cobbles and even boulders. Field studies located representative cobbles in the stream, marked them, and tracked their movement. This allowed correlation between pool scouring and specific streamflow amounts.

Lower flow studies were also important. How much trout habitat is available at lower flows typical in fall and winter? What are the stress points for fish? What are the water temperature impacts of different flows, given that upstream reservoirs can raise water temperatures? On this point, temperature models were created, and for Rush Creek the scientists came to interesting conclusions, including that Walker and Parker creeks provide critical cool water into lower Rush Creek, especially in drier years. This supported the “flow-through” requirements for these smaller tributaries, meaning that 100% of their water will pass through the diversion dams.

In the end, the streamflow requirements are made up of many components throughout the year. Would the streams benefit from high pool-scouring flows all year round? Definitely not, but a couple of weeks in the springtime are ideal. Would fish benefit from low baseflow conditions year round? Definitely not, but low flow in the winter months beneficially reduces stress on fish.

The flow requirements set in the 1990s were made up of just six different flow components during the year. The new SEFs contain up to 14 components, each specified and shaped to activate the natural processes that will restore the creek for which they were designed. This is a huge step forward in Mono Basin stream restoration—you could even call these flows “handcrafted.”

Once these critical flow amounts were determined, the shape of the annual Stream Ecosystem Flow plan, or hydrograph, came together (see Figure 2). Natural Eastern Sierra streamflows were a good point of reference, but these SEFs were determined specifically for the Mono Basin’s creeks. Different hydrographs were created for wetter and drier year types, reflecting the variable amounts of water provided by nature. Figure 2 shows how a wet year peak SEF will activate critical restoration processes that create physical changes in the Rush Creek bottomlands necessary for restoration of desired conditions.

A better future ahead

Seventy-five years ago, the Los Angeles Aqueduct was under rapid construction in the Mono Basin. Hundreds of people were at work, tunneling under the Mono Craters, constructing Grant Dam, and burying steel pipe to capture the flow of Rush, Lee Vining, Parker, and Walker creeks.

They accomplished great feats of engineering, and the purpose of the endeavor was crystal clear. “The general plan of operation,” wrote H. A. Van Norman, the Chief Engineer and General Manager of DWP at the time, “will be to divert the entire flow of the various streams … throughout the entire year.”

Mono Lake supporters know that the Committee’s 35-year history has, in many ways, been dedicated to changing that simple statement of purpose. Our goal, working together as tens of thousands of concerned citizens: A new plan of operation that recognizes the great ecological, public, wildlife, scenic, and economic values of Mono Lake and its tributary streams equally with the water needs of Los Angeles. We’ve had successes, the latest being the Stream Restoration Agreement.

One of the most notable things about the Stream Restoration Agreement is that it makes the aqueduct’s new, dual purpose a physical reality. The new Grant Outlet will show in concrete and control valves that the aqueduct can be overhauled—reconstructed—to serve both the goals of water supply for Los Angeles and, at the same time, the protection and restoration of Mono Lake and its tributary streams.

It’s also a significant and welcome change for DWP. This September, 75 years after Van Norman penned his simple statement of purpose, the present day General Manager Ron Nichols stood atop Grant Dam, endorsed the Agreement, and reflected on the construction era of the 1930s: “Environmental issues weren’t considered much, if at all,” he acknowledged. “We’ve come a long way. We have further to go, but the controversies, I believe, are narrowing.”

In the long run, this is the kind of change and accomplishment that makes all the negotiation, politics, detailed analysis, modeling, long phone calls, unending meetings, overnight document edits, and persistent hard work of recent years worthwhile. It’s what the Mono Lake Committee is here to accomplish. It’s what the Agreement parties have agreed to make happen. And it shows that we—Mono Lake supporters, Rush Creek enthusiasts, anglers, birders, Los Angeles residents, government agencies, and many others—can wisely shape the future to be better and healthier than the past.

_____________________________________________

Why streams, why now?

Protecting Mono Lake has always meant more than just putting water into the lake. It’s about protecting brine shrimp and migratory birds, restoring lost habitats, bringing back ecological health, and recognizing the interwoven tapestry of stream and lake resources that make this place remarkable.

Mono Lake’s political history and the 1994 State Water Board decision demonstrate this interwoven approach. The Committee was founded in 1978 and in 1983 won the landmark Mono Lake Public Trust decision from the California Supreme Court. Yet in the 1980s it was litigation over fish protection that first produced small yet continuous flows of water back into the lake. Then in the 1990s, protection of Mono Lake’s public trust resources resulted in the establishment of a management lake level that guaranteed substantial water for the streams in the process.

When the State Water Board issued its landmark decision in 1994, it had fish, streams, birds and waterfowl, and the lake at the core of its decision making. When restoration requirements were set, the State Water Board recognized that it could select a scientifically sound mandate for Mono Lake—6392 feet above sea level—but also recognized that it lacked enough information to definitively say what flow patterns should be required for the streams.

Instead, the State Water Board set stream restoration goals: return fish populations to good condition, and achieve restoration and recovery of functional and self-sustaining stream systems. Then the State Water Board launched a multi-year scientific endeavor to determine which streamflows would achieve these goals. This stream restoration study has been at the top of the State Water Board’s priority list for over a decade.

In 2010, the study bore fruit when the independent scientists produced the “Synthesis of Instream Flow Recommendations,” providing comprehensive flow prescriptions and restoration measures for all four damaged creeks.

Now, with the scientific report in and the restoration plan written, the Mono Lake Committee, DWP, CalTrout, and DFW have completed the final step by agreeing on how to implement the science-based plan.

So why streams, why now? In short, because the State Water Board said so. And in the bigger picture, because the lake and streams are forever entwined, and the streams were overdue to receive a restoration flow mandate—their equivalent of the mandated Mono Lake level. With that now resolved, both the lake and the streams have bright days ahead.

This post was also published as an article in the Fall 2013 Mono Lake Newsletter.