The word is that Godzilla has returned, and he might be coming to Mono Lake. A powerful El Niño has developed in the Pacific and at least one climatologist and a host of media sources are touting this event as a “Godzilla” El Niño.

The word is that Godzilla has returned, and he might be coming to Mono Lake. A powerful El Niño has developed in the Pacific and at least one climatologist and a host of media sources are touting this event as a “Godzilla” El Niño.

Godzilla’s storyline works. This was a monster that originally emerged from the ocean, and kept coming back. Through Godzilla’s various incarnations and movie sequels he took on a complex, mysterious, and powerful aura. He was not necessarily evil, nor was he good, but there was no stopping him. He trampled cities, battled other monsters, and was indifferent to everything in his path. He was the waltzing, overgrown sea-lizard of mayhem.

Monster drought needs a monster remedy

California is in the grips of its worst drought in history, and it continues to intensify. Mono Lake continues to drop and the Mono Basin is reeling. Since April 2012, the lake has declined 5.8 vertical feet in elevation over the span of 42 months. Increasing salinity, a growing landbridge, a wildfire that threatened Lee Vining, drying creeks, springs, and seeps, dying conifers, and stressed aspen stands highlight the drought casualty list.

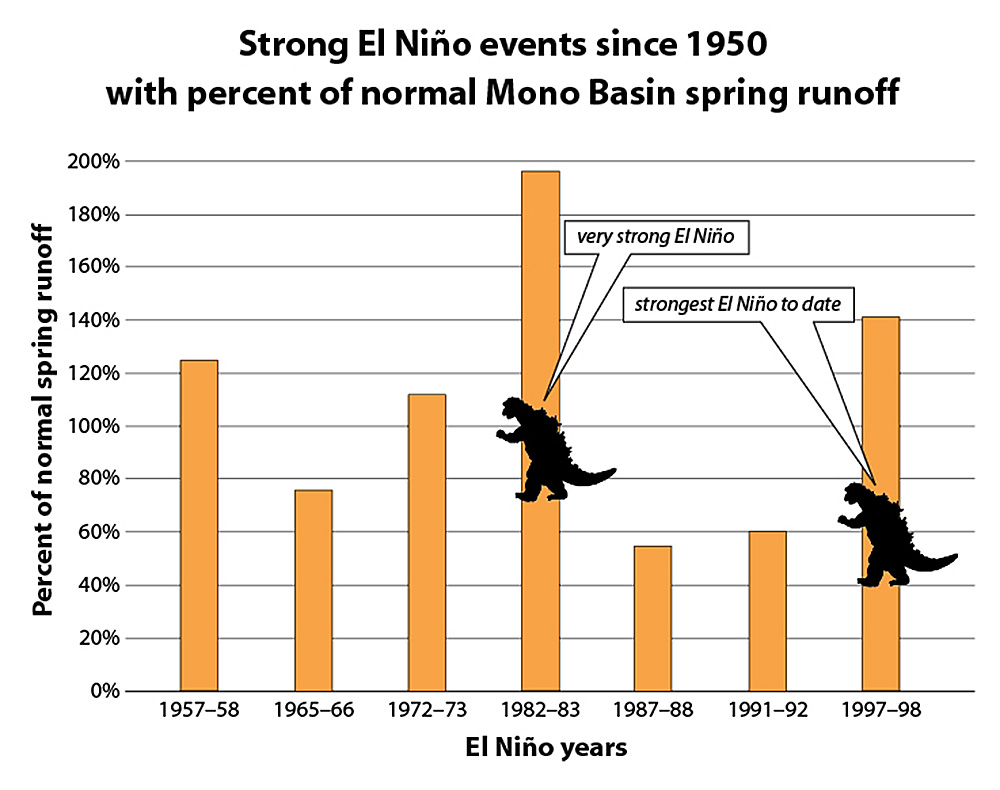

The two strongest El Niño events since 1950 have brought monster-like winters to California (see graph below). If it turns out that Godzilla has returned, and he can subdue the drought, then let him come to Mono Lake!

Mythological expectations and modest data

If we want to anticipate what might happen this winter, it helps to look back at the strongest El Niño events with an Oceanic Niño Index (ONI) of over 1.5° Celsius, which is in line with the current projected strength of this year’s El Niño.

Looking back through the El Niño record since 1950, there have been seven events that have sustained an ONI around +1.5°C or greater. This is a measure of the surface temperature anomaly in an area of the Pacific called the Niño 3.4 region, sustained over multiple months and seasons. No El Niño is exactly the same, and the ONI is just one way to measure the strength of an El Niño; however, it is the standard by which the National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) defines El Niño and La Niña events.

Based on model projections, the current El Niño may be among the strongest on record. It takes a very strong El Niño to get the nickname “Godzilla” (unofficially +2.0°C to qualify). He has appeared twice before, in 1982 and 1997, with an ONI of +2.2°C and +2.3°C respectively. Godzilla events were a great benefit to Mono Lake in both those years, but for the seven strongest El Niño events, the record in the Mono Basin is mixed. Four of the seven have led to above-average spring runoff, while three have resulted in below-average runoff. In other words, the strength of an El Niño does not directly correlate to the amount of runoff the Mono Basin will get (see graph).

There is reason for cautious optimism as we go into this winter, but there are no guarantees, and a sample size of two very strong El Niños does not instill high confidence. The last time Godzilla appeared, the Pacific was cooler and there was less human-produced CO2 in the earth’s atmosphere. Since then the science of climate change has advanced, along with our realization that human-caused greenhouse warming is influencing the climate in unforeseen ways. Will a strong El Niño result in the same atmospheric response that brought a parade of storms to California in the past? All eyes are on this mighty El Niño.

This post was also published as an article in the Fall 2015 Mono Lake Newsletter (pages 5 & 9).