It’s the early afternoon and I’m standing in Mill Creek on July 30, 2015. The sun is warm when you stand in its rays and the cool softly flowing water is refreshing and welcomed. Standing still I can see bees and butterflies dancing among violet pink, periwinkle blue, and bright yellow wildflowers. It’s hard to believe that two months ago, this particular stretch of Mill Creek was almost entirely dominated by invasive white sweet clover (Melilotus albus).

White sweet clover plants can live for 2–3 years before casting thousands of seeds and dying. The seeds are hard and light (ideal for stream transportation) and have been shown in some cases to stay viable in soil for 30 years! While the plants tend to grow 3–5 feet tall, some plants grow to double that size. If left unchecked, white sweet clover can easily dominate riparian (streamside) habitats due to their plant size and large production of durable and persistent seeds. Because there are still large sections of Mill Creek without white sweet clover, the Mono Lake Committee has spent the last five years or so working to manage the invasive plant population with the help of staff and volunteers.

The effort has evolved over the years, but the overarching goals have always been to: (1) protect manageable ecological habitats in the Mono Basin from noxious invasive plants, and (2) raise awareness about invasive plants to a broad community. But in July 2015, we tried something different to enhance these objectives: We took a group of 13 students attending the Mono Lake Committee’s Outdoor Education Center (OEC) to Mill Creek.

It worked out that the OEC group had some time one morning to go out into the field with me to remove white sweet clover as part of their Mono Basin experience and we thought this could be a great way to offer some information to a younger audience about the impacts of invasive plants. Not knowing the group’s level of interest, I planned to spend some time telling them about the work I do, about invasive plants, about stream ecosystems, and how I’ve come to develop a removal strategy based on that information. It became clear very quickly that the kids did not connect with the topic … at first. But the more I explained, the better their focus became and the more questions they began to ask. When we started to remove the invasive clover, I could tell the kids were excited as they continued to ask me questions while they tirelessly removed the invasive plants. Before we knew it, we had removed an astounding 145 pounds of sweet clover.

Because this was the first time that we had taken an OEC group to Mill Creek to remove invasive plants, I was really interested in hearing feedback about their experience. The students and the group leaders all felt that it was a fun activity, that it was really informative and inspiring, and that every OEC group should get to do this activity. This summer in 2016 I think we will take their advice.

After spending a couple days removing the invasive clover from a site on Mill Creek with OEC groups and other volunteers, native clover and other delicate flowers can quickly recapture a space, making the ecosystem ecologically and aesthetically more diverse. Standing in the stream and gazing out at the result from our work is surely worth a stop to smell the wildflowers.

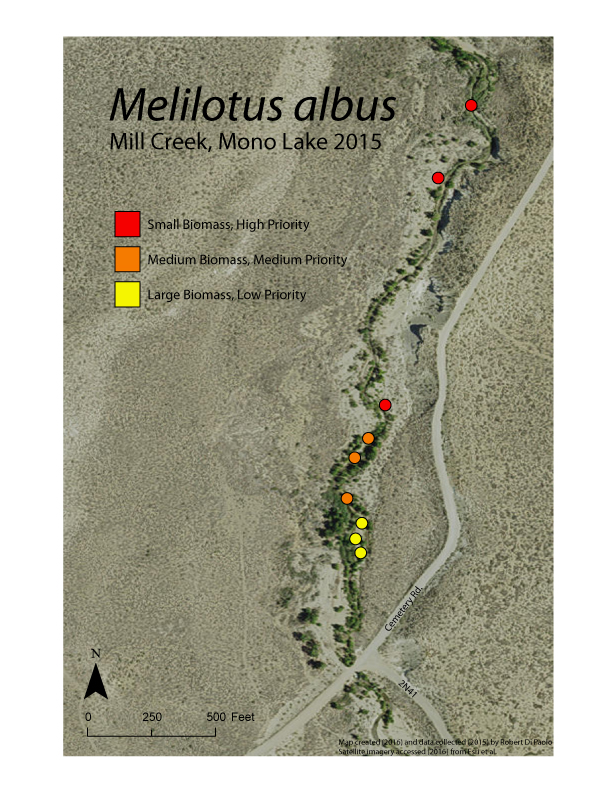

I know farther downstream there are fields of white sweet clover, but our efforts upstream are making a noticeable difference. We will continue to prioritize areas along Mill Creek where the white sweet clover is only starting to appear, where we can get and stay ahead of its spread. But the opportunity to inspire young people to think critically about their environment and take an interest in environmental stewardship? Well, that’s pretty sweet too.

Special thanks to outdoor clothing company Patagonia Inc. for their support of the Mono Lake Committee’s restoration stewardship program.