It’s an old story. A State Fisheries biologist is assigned to a remote area and begins patrolling and documenting the abundant fisheries there. He becomes concerned when upstream water diversions start to degrade the riparian ecosystems that he was assigned to protect. Stepping into a political minefield, he shares his concerns with his supervisors. He is told to back off and mind his own business.

At Mono Lake this story began in 1938 when Elden Vestal was assigned to the Eastern Sierra as one of California’s first professional Fish & Game biologists. In 1941, after “becoming deeply disturbed about the state of Rush Creek” due to the onset of stream diversions by the Los Angeles Department of Water & Power (DWP) he “wrote the Chief of the Bureau of Fish Conservation. The reply was a thinly veiled warning to stop my investigations into what was apparently a very sensitive political question.”

Elden’s story lent an aura of deja vu to a lecture I recently attended, entitled “The Fisheries History of Walker Lake, Nevada: Past, Present, and Future!” The presenter, Mike Sevon, was a fisheries biologist for the Nevada Division of Wildlife (NDOW) for 35 years and was responsible for managing the fishery at Walker Lake. He gave a concise, thorough, and personal account, which I summarize here.

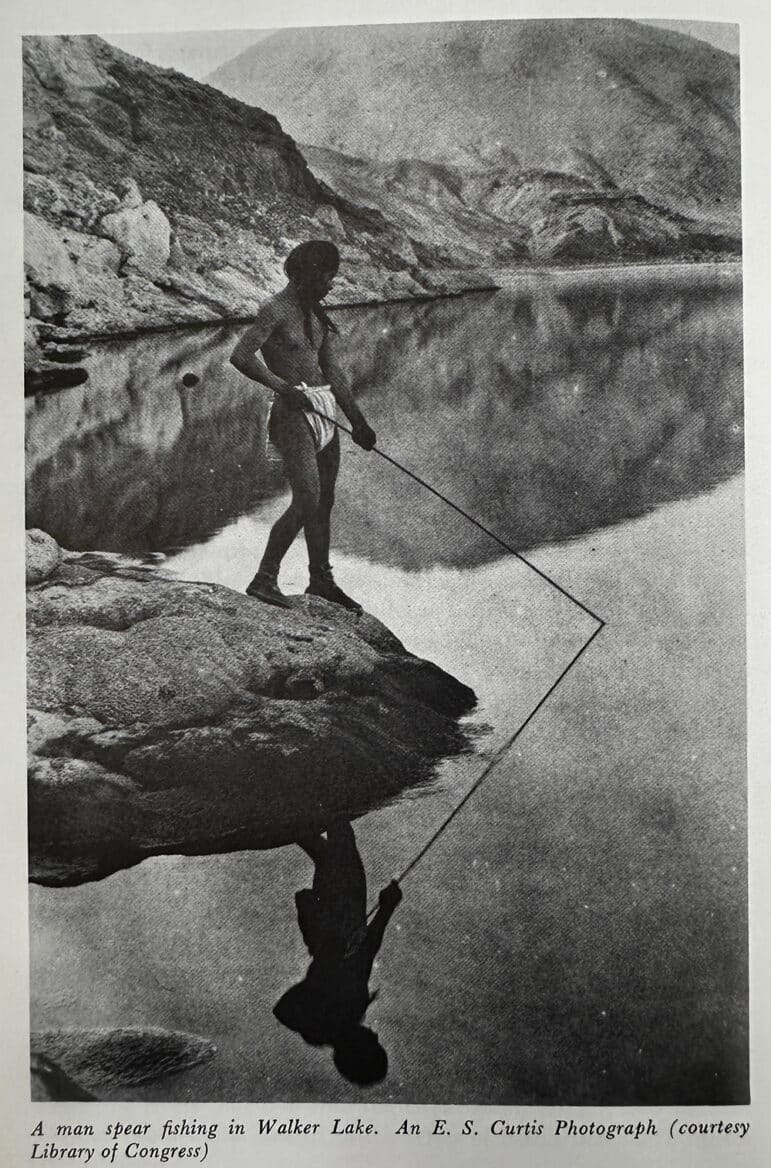

Walker Lake, in Mineral County, Nevada (about 40 miles northeast of Mono Lake) is a Great Basin freshwater terminal lake. It is the southernmost remnant of Pleistocene Lake Lahontan, which as recently as 13–14,000 years ago stretched all the way into Oregon. This allowed Yellowstone cutthroat trout to enter the lake through the Snake River drainage. These fish evolved into the present-day Lahontan cutthroat trout, which are the largest trout in North America. Along with tui chub and Tahoe sucker, the trout provided a major food source for the Walker River Paiute Tribe, the Agai Dicutta, or “trout eaters.”

Early explorers included Jedediah Smith in 1827 and Joseph Walker in 1833. Upstream agriculture was established and the first water right was granted in 1859, beginning Walker Lake’s decline. Dams built at Topaz and Bridgeport prevented the trout from swimming nearly 100 miles upstream to spawn in Sierra Nevada lakes and streams.

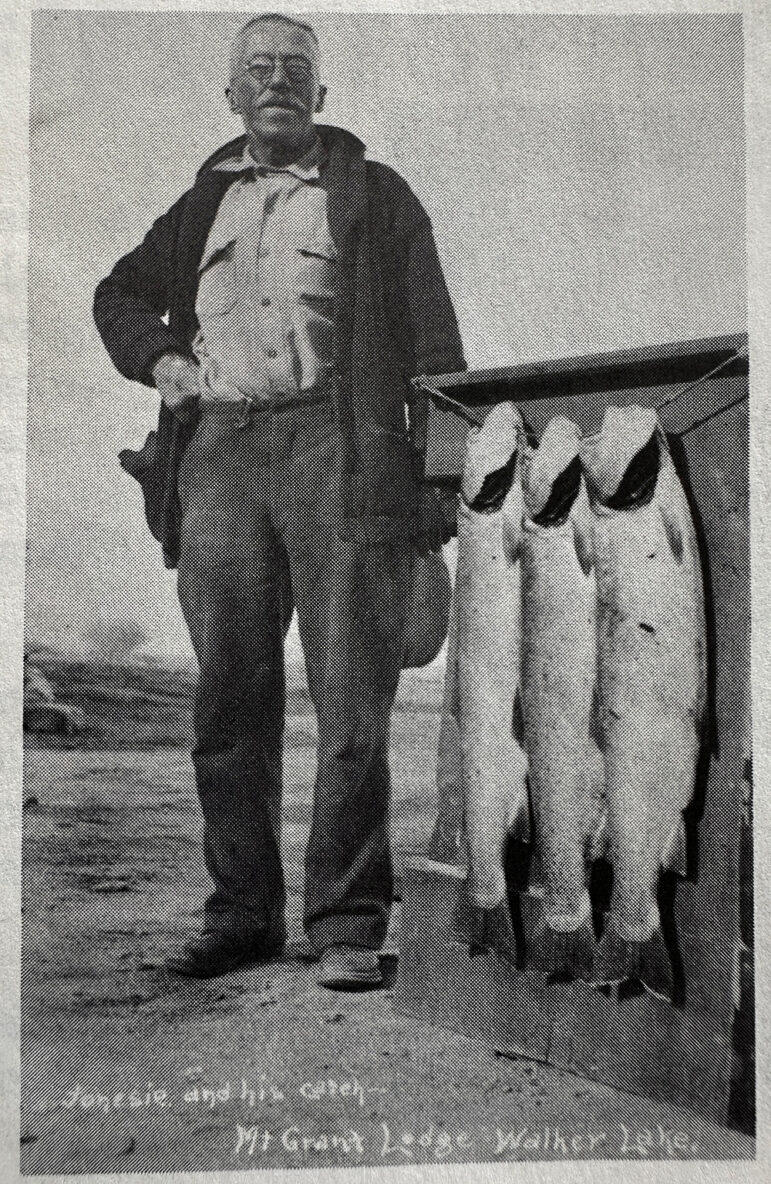

The railroad built along Walker Lake’s eastern shore during the 1880s created a market for commercial fishing and gave access to recreational fishing, which started the tradition of Walker Lake Fishing Derbies. These derbies had a dramatic effect on businesses in the nearby town of Hawthorne, filling up its restaurants, motels, and casinos with anglers seeking prizes that included boat-motor-trailer packages and cash up to $25,000. When the Walker Lake fishery was healthy it was responsible for more than half of Mineral County’s yearly economy.

As the lake level of Walker Lake declined the amount of salts and minerals in the water (total dissolved solids) increased, causing its fish to become ever more stressed.

1971–1974: Catch averaged 150 fish over 5 pounds

1975–1979: Catch averaged 33 fish over 5 pounds

1980: One fish over 5 pounds (This was the year Mike Sevon arrived at Walker Lake.)

Fortunately, 1982–1983 were wet years. Inflow to the lake increased by 28%, the fish lived longer, got bigger, and Mike’s popularity increased dramatically among the locals. He continued to raise the plight of the lake with evidence of how the fishery was to decline in the near future, which lead to the creation of the Walker Lake Working Group. Although NDOW and the US Fish & Wildlife Service stocked 200,000 yearling cutthroat trout each year from 1980 to 2000, as the lake’s salinity rose, the stocked fish had to be pre-acclimated by placing them into tanks filled with a solution of freshwater and lake water.

Overshadowing all these efforts were two unyielding facts: 1) The water of the Walker River was over-allocated to the point that it took more 120% of normal flow to satisfy water rights holders. 2) Walker Lake loses about four vertical feet of water yearly to evaporation.

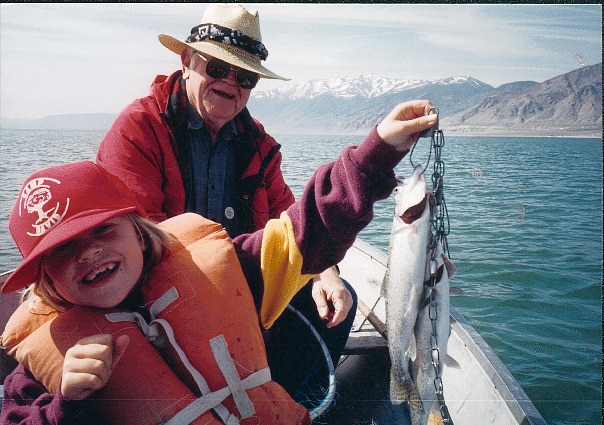

By the end of 2010 Walker Lake’s last remaining species of fish, Lahontan cutthroat trout, died off. Mike put up a very poignant image of kids on the shore of Walker Lake holding up fish they had just caught. Underneath was the caption, “A legacy taken from our children.”

After concluding his talk, Mike introduced Peter Stanton, Chief Executive Officer of the Walker Basin Conservancy, and Glenn Bunch, President of the Walker Lake Working Group.

Peter succinctly explained the roles of the two organizations; “We (the Conservancy) are the carrot, and they (the Working Group) are the stick.”

The Conservancy purchases water and land from willing sellers. They have acquired 55% of the water necessary to restore Walker Lake’s fishery, restored purchased land to its natural condition, and donated more than 12,000 acres of land and 30 miles of the East Walker River to help establish the Walker River State Recreation Area.

The Working Group, in conjunction with Mineral County, has paid legal costs for the Walker Lake Public Trust trial, currently in the discovery phase at the US District Court in Reno, Nevada. This case has been the driving force behind the effort to save Walker Lake and has already resulted in the Public Trust Doctrine being established in Nevada.

The battle for Walker Lake has reached about the same point that the battle for Mono Lake did in the early 1990s. At that time, Mono Lake’s lawyers were told that they should go talk to a retired fisheries biologist named Elden Vestal. Elden welcomed them into his garage, revealing stack after dusty stack of detailed notes, records, and photographs that gave a clear picture of Mono Lake’s streams before the extension of the Los Angeles Aqueduct into the Mono Basin and stream diversions began. Elden’s subsequent roles as star witness in court, and later testifying before the California State Water Resources Control Board, were crucial in establishing the protections that Mono Lake and its tributaries enjoy today.

Sometime next year, Mike Sevon will take the stand in Reno Federal Court. In the highest tradition of public service, Mike will use his notes, records, photographs, and personal experience in making it clear to the court that the death of the Walker Lake fishery was an unnecessary loss of one of the state of Nevada’s greatest natural treasures.

Mike will also be indirectly advocating for a small group of fish living in a reservoir in the Wassuk Range, the mountains that rise abruptly from Walker Lake’s western shore. In these shallow waters live the last of Walker Lake’s tui chub. These fish were removed from their native habitat in Walker Lake before being overwhelmed by the rising salinity. They wait silently for Walker’s restoration.

Click here to donate to the Walker Lake Working Group

Top photo courtesy of Mike Sevon Photos.