A mile of citizen-funded solar-powered electric fence is up and running, protecting Mono Lake’s nesting gulls—one of the three largest colonies in the world—from mainland predators. The fence is the result of a year and a half of planning by the Mono Lake Committee and California State Parks along with other agency partners, a dedicated local installation team, and generous funding from Mono Lake supporters across the country.

Why is the temporary fence—which will be removed when nesting is finished—needed? Five years of drought lowered Mono Lake seven feet, shrinking the protective moat of water between the lake’s north shore and Negit Island and adjacent islets—exposing a landbridge that allows coyotes access to the lake’s long-established nesting colony of California Gulls. Last summer signs were found on a few of these islets that coyotes had indeed walked the landbridge and then swum the remaining 500 feet or so of shallow water to prey on eggs and chicks, disrupting nesting and causing gulls to be suspicious of returning to these sites in future years.

Not a typical fence site

The electric mesh netting fence used for the project comes from a company whose catalog features photos with lush green pastures where the fence product is easily moved by truck and the firm ground holds up fence posts to protect livestock from coyotes. The task at Mono Lake was to take this proven-effective fencing and install it more than a mile from the nearest road, on exposed silty lakebed known for its thigh-sucking mud qualities, in a barren environment subject to 70 mile-per-hour winds and baking sun. Not to mention that the ends of the fence run into Mono Lake, so there is water, wave action, and the rising lake level to contend with.

The local installation team did an excellent job, aided by their knowledge of the lake and ability to be flexible with changing weather conditions. Materials were moved to the site by boat, which required watching carefully for breaks in the winter weather for safe conditions. Installation required dispersing and assembling rolls of fence material, hundreds of fence posts, solar charger units, and more along the mile-long fence line. It also required some innovative methods, such as long wooden planks laid across shoreline spots where a person walking would, literally, sink to their waist in mud.

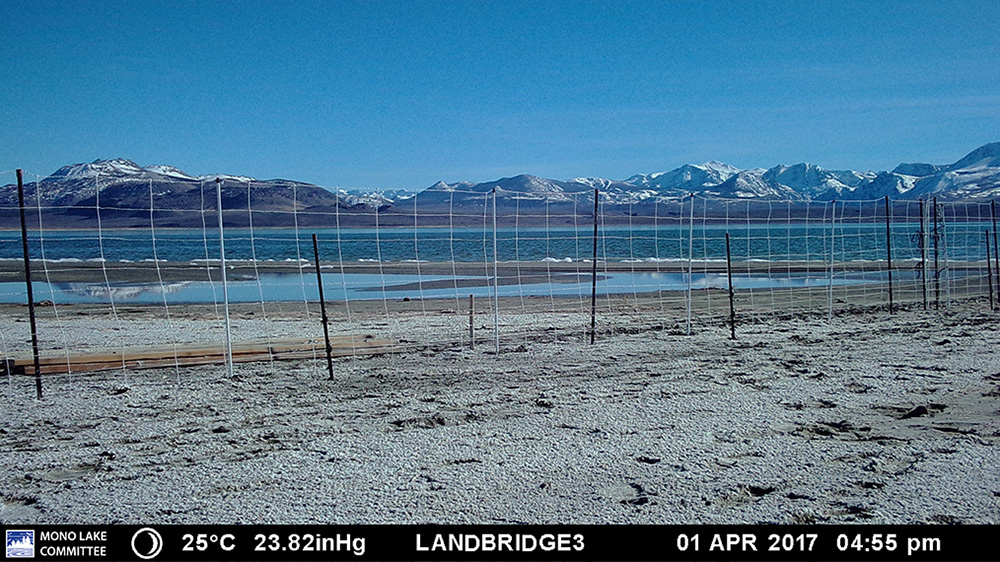

The fence was installed and electrified by the April 1 target date and has since worked well through a variety of harsh conditions including snowstorms, heavy rain, and severe windstorms. The fence includes the main electrified mesh netting as well as an electrified anti-digging wire along the length of the main fence. The fence is cleverly made up of five sections that overlap—an electrified long middle section, two shorter electrified sections at the ends near the water’s edge, and two passive sections at the ends that extend out into the water where electrification is not possible. Mono Lake is rising, so routine inspection of the fence and adjustment of the ends is ongoing; however, the design ensures that if lake water were to temporarily short out one of the electrified end sections, the majority of the fence would remain charged.

Monitoring for effectiveness

With the fence in place, the big question of course is: is it stopping coyotes? Wildlife cameras and field observations indicate it is.

During installation numerous fresh coyote tracks were documented on both sides of the fence route, and on the edges of Negit Island. Follow-up field observations have found that since the fence went into operation there have been no new tracks on the “wrong” side of the fence. Two sets of coyote tracks on the “right” side appear to show a direct approach to, and abrupt retreat from, the fence.

The Committee installed 11 motion-activated wildlife cameras with infrared nighttime flash capability along the fence line to capture coyote activity. The fence is long enough that the cameras cannot cover its full length, so cameras are clustered at the fence ends, where tracks suggest coyotes actively walk the shoreline, with a few scattered along the dry interior section of the fence. Coyote photos have been rare so far, but on an April evening camera #5 documented a coyote walking the fence line, looking, one might guess, for a way to get to the other side (see photo above).

The Committee and volunteers will continue to maintain the cameras throughout the summer and will be closely monitoring the fence, including looking for any areas where improvements need to be made.

As a reminder, a one-mile radius around Mono Lake’s islands is closed to people from April 1 to August 1 each year to protect the nesting birds. The area where the fence is located is included in this closure and the fence maintenance team has special permission to work the fence line. If you’re visiting Mono Lake this year, please do not include a trip to the landbridge in your itinerary—we are posting frequent updates and photos about the fence throughout the nesting season on our website, so please stay tuned here to the Mono-logue instead.

Big winter makes a difference … for next year

When Mono Lake rises, it will cover the landbridge and restore the natural watery protection that the gulls have relied on for safety for centuries. Indeed this is one of the key objectives of the mandated lake level set by the State Water Board to protect Mono Lake.

More than three feet of that lake rise is happening this year, thanks to the very wet winter that created a snowpack exceeding 200% of average in the Mono Basin. As the winter progressed, Committee staff modeled and re-modeled the lake level rise to see if the fence would truly be needed. Gulls start nesting in April, and the key time period for nesting safety is April through July. However, winter snows don’t typically melt enough to significantly raise Mono Lake’s level until around June. That’s too late for the gulls, and so we proceeded with the fence project. Mono Lake’s summer and fall rise, however, makes it likely that the fence will not be needed in 2018, although we’ll wait until next winter before making any final decisions.

Crowd-funding a fence

In February, when the first returning gulls of the season were spotted, the albeit confusing reality of needing to put up a fence to protect the gull colony was sinking in.

We had hoped that with all the rain and snow there wouldn’t be a need for a fence, but were prepared with plans, permits, and people just in case. Luckily, in December, an amazing thing had happened—we received an unsolicited, and significant, donation from a thoughtful Mono Lake Committee member specifically for the fence. By our calculations, we were going to need an additional $15,000 in order to fully fund the fence.

That fortuitous donation made us wonder if we could crowd-fund the difference. We launched the #LongLivetheGulls campaign on Indiegogo, complete with a video and gull-themed perks, on February 15. We watched the campaign with anxious anticipation—every single donation felt like a little miracle. By March 28 we had raised $15,460 from 231 backers, and were able to order the fence materials in time!

Many thanks are in order for all who contributed. Thank you for chipping in. Thank you for telling your friends. Thank you for making the fence a reality. And, most importantly, thanks to you the fence is up, and the gulls have a much better chance of a successful nesting season.

This post was also published as an article in the Summer 2017 Mono Lake Newsletter (pages 4 and 23). Top photo courtesy of Point Blue Conservation Science.