Researchers at the University of California, Berkeley discovered a new organism living in Mono Lake’s water—a species of choanoflagellate they named Barroeca monosierra.

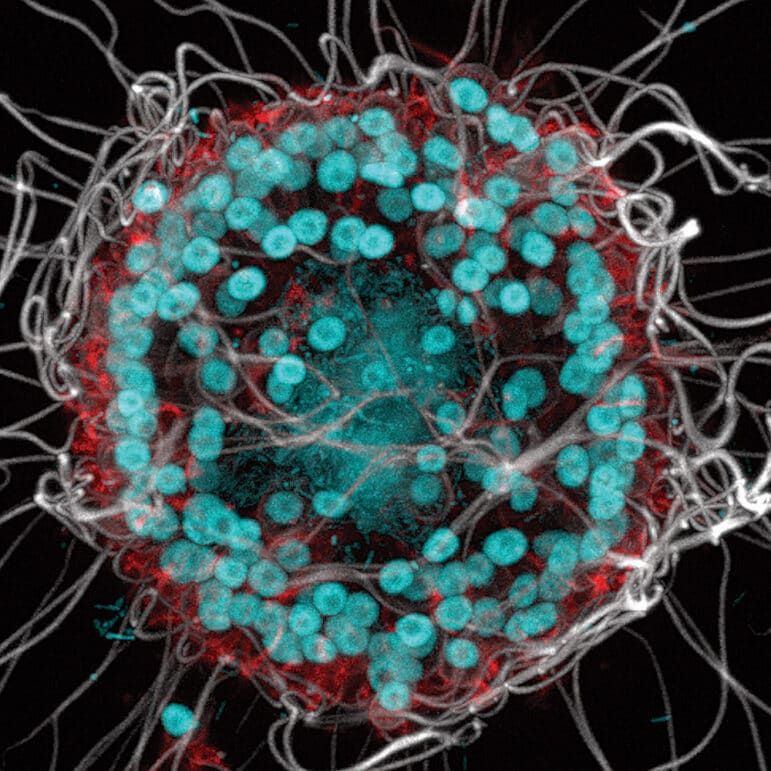

Choanoflagellates are single-celled, microscopic organisms that primarily feed on bacteria. Scientists have found that B. monosierra is unique because instead of only consuming bacteria, the organism forms large colonies that contain live bacteria and form a stable relationship with them. “To our knowledge, this is the first report of such an interaction between choanoflagellates and bacteria,” reads the researchers’ paper, which was published in the American Society for Microbiology.

Because choanoflagellates are the closest living relative to animals, B. monosierra can provide valuable insight into the ancestry of animals, and their evolution from single-celled organisms into multicellular ones. This species’ unique relationship with bacteria might make it even more helpful in this regard than other species of choanoflagellates.

The Mono Lake water that B. monosierra lives in is hypersaline, alkaline, and contains chemicals like arsenic. Though this chemistry may sound harsh and unlivable, it actually creates the conditions that specific forms of life need in order to thrive. For example, the brine shrimp that live in Mono Lake, Artemia monica, don’t live anywhere else in the world. The discovery of a previously unknown choanoflagellate shows us more about why Mono Lake’s environment is so critical for many forms of life.

That’s one reason why the long, rich history of scientific research in the Mono Basin forms the basis of the Mono Lake Committee’s work protecting Mono Lake. From the 1976 study that documented the devastating ecological impact of Los Angeles’ excessive water diversions, to new discoveries such as this one, science is one important part of better understanding and sharing what makes this place important.

The team of Berkeley researchers that described B. monosierra includes Nicole King, a UC Berkeley professor of molecular and cell biology, Jill Banfield, UC Berkeley professor of environmental science, Daniel Richter, a UC Berkeley graduate school alumnus, and current Berkeley graduate student Kayley Hake.

These scientists found B. monosierra in a Mono Lake water sample Richter took around ten years ago, which a group of Berkeley graduate students including Hake recently revived and began to look at more closely.

“It was just packed full of these big, beautiful colonies of choanoflagellates,” King said in recent article published in UC Berkeley News. “I mean, they were the biggest ones we’d ever seen.”

Top photo by Caelen McQuilkin.