The Wilson’s Phalarope is an iconic bird of saline lake ecosystems and a species of rising conservation concern across its range in the Western Hemisphere. A coalition of scientists and conservation groups filed a legal petition to list the Wilson’s Phalarope as “Threatened” under the US Endangered Species Act (ESA). This is how the US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) considers a species for listing.

The petition is an extensive scientific document detailing the ecology and threats to the species, focusing on how the species qualifies as Threatened under the law. Following are some of the key findings directly from the impressive 118-page document.

Unique natural history

Among shorebirds, the Wilson’s Phalarope stands out for its unusual behaviors, diet, migration, and habitat. This species does not fit neatly into the “typical shorebird” paradigms.

Like other phalaropes but unlike all other shorebirds, Wilson’s Phalaropes spend most of their time swimming, rather than walking on the shore. While swimming, they often spin in circles to create a vortex drawing prey to the surface.

Breeding phalaropes reverse the typical sex-roles: females are larger and more colorful than males, and they actively vie for the males’ attention. Once a mate is secured, the females lay the eggs and leave the caring for the eggs and chicks entirely up to the males.

Their southward migration is a unique “molt migration” where they travel to specific areas where they undergo a complete replacement of body feathers before continuing the rest of their journey.

During the molt migration, Wilson’s Phalaropes depend on hypersaline lake habitat, mostly in the interior of North America. At these sites, Wilson’s Phalaropes more than double their body weight and engage in one of the fastest complete molts of body feathers documented in birds, all in a few short weeks.

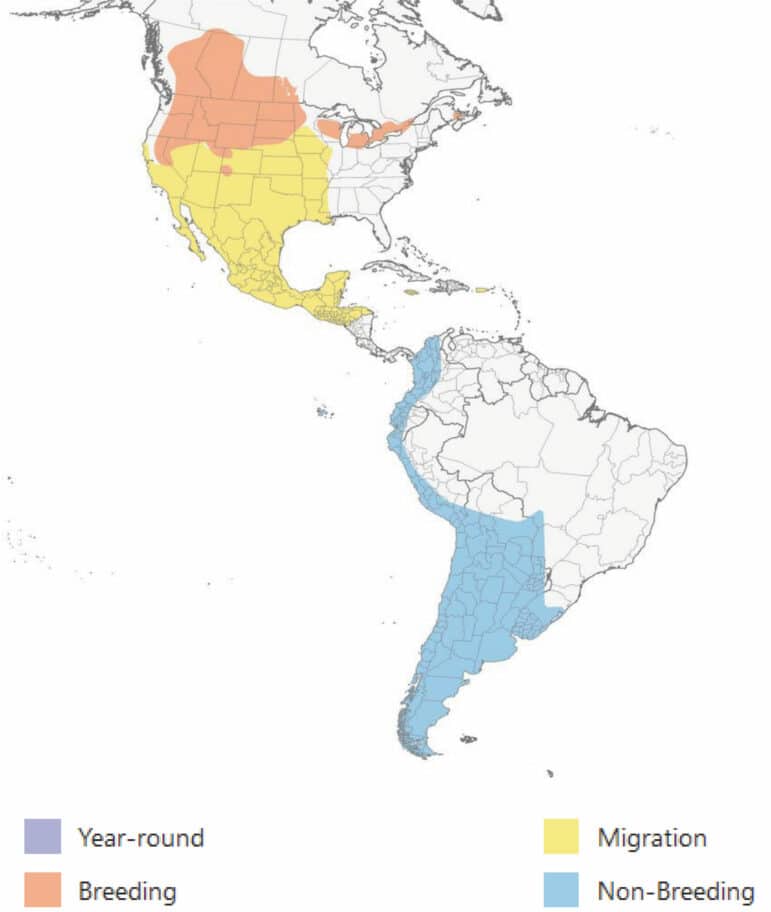

After stopping for their molt migration, Wilson’s Phalaropes embark on an epic migration of approximately 3,500 miles to South America.

A highly specialized species

The Wilson’s Phalarope relies heavily on just a few key sites during a crucial part of its annual cycle. The staging period, in which Wilson’s phalaropes congregate in large numbers at Great Salt Lake, Lake Abert, and Mono Lake, is a key energetic pinch-point in which they must rapidly double their weight and molt feathers for the subsequent long-distance migration.

The Wilson’s Phalarope is highly specialized to inhabit saline lakes. The incredible migration of phalaropes, from North American breeding grounds to South American wintering areas, is fueled by the energy gleaned from feeding at saline lakes. Up to 90% of the world’s adult population can congregate at a time at just three saline lakes in western North America: Great Salt Lake in Utah, Lake Abert in Oregon, and Mono Lake. At these sites, they undergo rapid feather molt and double their body weight by eating alkali flies and brine shrimp.

Phalarope habitat loss

Although Wilson’s Phalaropes have a large range and relatively large population, the dependence of large portions of the world population on just a handful of major staging sites means they could rapidly decline if those sites disappear.

From wetland loss in the breeding grounds to lithium mining polluting the wintering grounds to the desiccation of saline lake migratory stopover sites, phalaropes are rapidly losing habitat across the continents where they live.

In particular, excessive inflow diversions of fresh water and climate change pose significant threats to the saline lake habitats that Wilson’s Phalaropes depend on. Put simply, critical saline lakes like Great Salt Lake and Lake Abert are in danger of completely drying up, becoming desiccated salt flats that offer no food or habitat for phalaropes or any other wildlife.

Since the 1980s, total global numbers of Wilson’s Phalaropes have declined by about 70%, with similar downward trends reported at key sites across the Western Hemisphere, including areas in California, Utah, Oregon, Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, and Peru.

The ESA petition underscores the urgent need for holistic conservation efforts that safeguard the habitats essential for the survival and viability of the Wilson’s Phalarope.

How many Wilson’s Phalaropes are there?

Many pages of the petition are devoted to documenting the various efforts that have been made to document the size of the global population of Wilson’s Phalaropes over time. Between different survey methodologies, timing, and locations, it is difficult to give a precise global population number.

From the 1980s to present, the most frequently used world population estimate for the Wilson’s Phalarope has been 1.5 million individuals, though subsequent reports and analysis have listed the 1.5 million estimate as of low accuracy.

In 2020, a survey was completed across the Wilson’s Phalarope non-breeding range in South America with the goal of obtaining a new world population estimate. The total number of birds directly counted in the non-breeding range was 854,673, but based on coverage calculations and error estimations, it was suggested to set the estimate of the Wilson’s Phalarope population at 1 million individuals.

At Mono Lake, the highest published estimate of Wilson’s Phalarope numbers is 93,000 from a single survey in 1977, followed by 77,950 in 1988. Annual lake-wide peak counts from 1980–1990 averaged 49, 590 birds. From 1990–1997 the average annual peak count was 22,566, representing a decline by over half from 1980s totals.

Scientific analysis of available surveys shows there was a major decline of phalarope numbers at Mono Lake from the 1980s to the 1990s and that their numbers have not recovered to 1980s levels.

The relatively large counts at Mono Lake compared to smaller sites, and the use of Mono Lake when other sites are dry, underscores its importance as a staging site for the species.

The recent analysis of International Shorebird Survey data (ISS) by USFWS and Canadian Wildlife Service authors found an approximately 70% decline in abundance of the species in the U.S. and Canada since 1980.

No existing protections for the Wilson’s Phalarope

Currently, the Wilson’s Phalarope holds no federal protection under the ESA. The Migratory Bird Treaty Act only offers very limited protection from purposely killing birds. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) lists Wilson’s Phalaropes as a species of “Least Concern” with a reported population trend of “Increasing;” however, that status is outdated and was set without incorporation of the research finding a 70% population decline in the species, nor does the status take into account the rapidly worsening and highly critical condition of saline lake habitats. The ESA petition filed today highlights the fact that based on both historic and contemporary population trajectories, the Wilson’s Phalarope may qualify to be listed as “Endangered” by the IUCN.

Next steps for the ESA petition

The petition that was filed today is the first step in what is often a lengthy process of consideration for ESA designation by the USFWS. The petition is a request for USFWS to consider the species under its 90-day finding, in which it will decide whether the request to consider the species is scientifically sound. If so, the USFWS will conduct their own review, and issue a two-year finding declaring whether the species should be listed under the ESA or not.

In practice, this process often takes many years longer than two years, but the petition is an important milestone in starting the process. The Wilson’s Phalarope is a powerful reminder of the interconnectivity of the natural world, as well as the potential that humans hold to alter the integrity of these systems, for better or for worse. Protecting the Wilson’s Phalarope is not only about preserving this single species; it’s about conserving a hemisphere-wide network of habitats that, together, create something much larger than the sum of its parts. Without immediate action and legal protections such as those provided by the Endangered Species Act, the longevity of the Wilson’s Phalarope—and saline lakes—are at risk of being lost.

For more on phalaropes

- Petition to list the Wilson’s Phalarope under the Endangered Species Act

- Endangered species protections sought for a Mono Lake favorite: Wilson’s Phalarope’s

- Current science efforts: International Phalarope Working Group meeting at Laguna Mar Chiquita in Argentina

- March 28, 2024 Press Release: Endangered Species Protections Sought for Wilson’s Phalarope

- Tracking phalaropes at Mono Lake and beyond

Top image courtesy of Ron Ozuna.