This post was written by Kevin Brown, 2019 Information Center & Bookstore Assistant.

April 16, 1988 will never share a place of honor alongside key moments in the Mono Lake Committee’s history—such as the date of the California Supreme Court’s public trust ruling (February 17, 1983) or State Water Board Decision 1631 (September 28, 1994). Yet this early spring day 31 years ago represents an important, if little known moment: on that Saturday the Committee started keeping track of the weather.

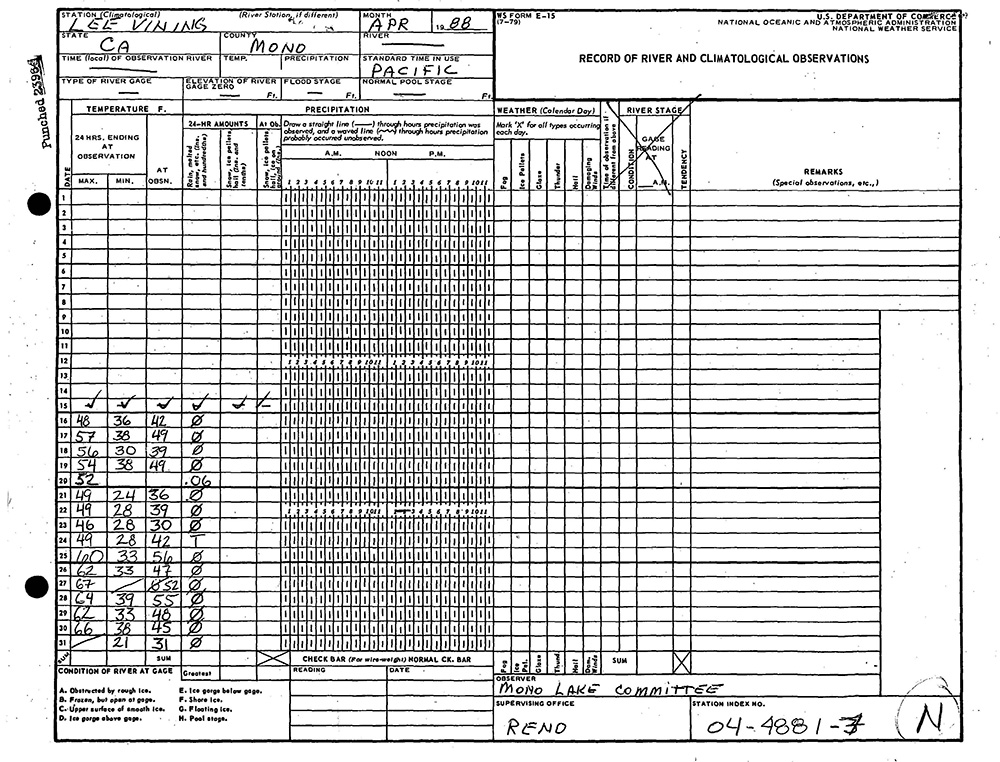

Recording a maximum temperature of 48°F, a minimum of 36°F, and no precipitation, this information formed the first set of observations submitted from the Lee Vining Station to the Cooperative Observer Program at the National Weather Service.

The Cooperative Observer Program is the nation’s longest running weather observation program, dating back to 1890. Today, there are more than 8,700 stations like the Committee’s that participate, recording weather data in locations across the country.

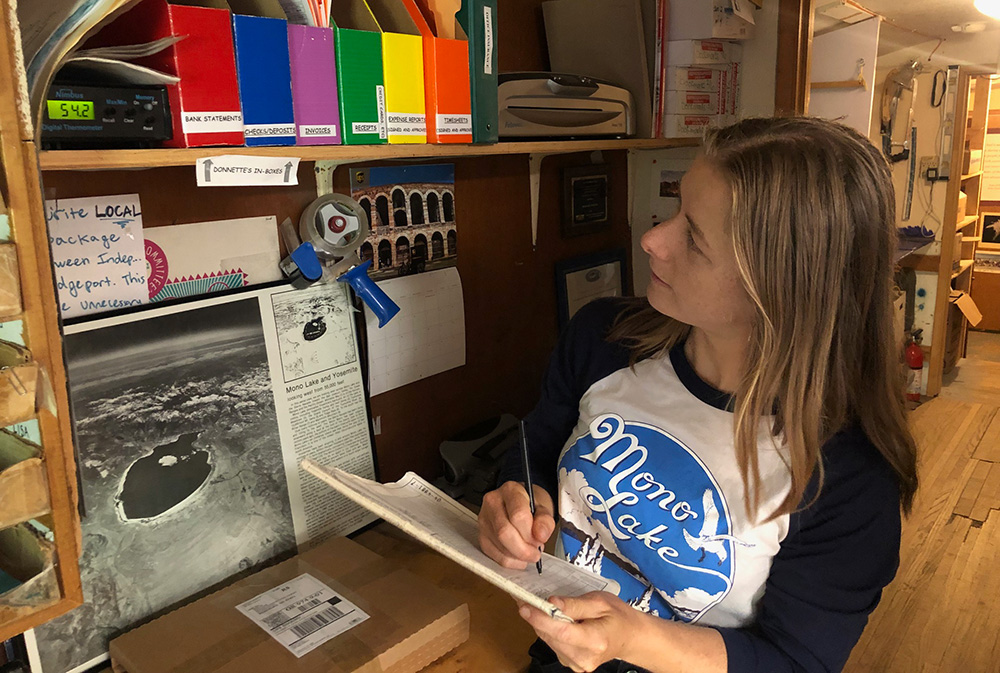

In Lee Vining, the weather data collection program continues much as it did 31 years ago. Every morning at the Committee office, we read the digital thermometer, recording the current temperature, as well as accessing the maximum and minimum temperatures from the last 24 hours. Then we check the rain and snow gauging station outside. (This February, our station recorded 53.3 inches of snow!) After gathering this information, we submit it all to the National Weather Service.

The data collected by cooperative weather stations like the Committee’s provides long-term data for researchers to assess changes in climate. Just a few years ago scientists used data from our station in Lee Vining in a paper estimating the amount that snowpack will decline in the Eastern Sierra as the climate warms.

The anniversaries of our weather station have come and gone mostly unnoticed. Recording this information is not difficult, does not take much time, and has no immediate payoff. But every day we add another line on the data sheet, and contribute to a better understanding of how the weather in Lee Vining and the Eastern Sierra are changing over time.