This summer Los Angeles Times writer Ian James joined a South Tufa tour for the public led by Mono Lake Committee Education Director Ryan Garrett. He wrote a poignant piece about the experience of both the curious landscape and the “stark introduction to 80-plus years of Los Angeles’ water use.”

A South Tufa tour is essentially Mono Lake 101—complete with interactive lessons in ecology, geology, biology, chemistry history, law, anthropology, and political science—woven together into a one-hour telling of the Mono Lake story.

As they walk toward the shore, the group is dwarfed by the lake’s famous craggy formations called tufa nearly 20 feet above them. [Ryan] Garrett stops to describe how the towers of calcium carbonate grew underwater around freshwater springs over thousands of years, then were left exposed as the water dropped.

“If we were here in 1941, we would be underwater,” he says.

The lake’s threatened health became a rallying cry in the 1980s, when “Save Mono Lake” bumper stickers appeared on cars across California. In 1994, state regulators ordered the L.A. Department of Water and Power to take steps to raise the lake 17 feet by taking less water from the creeks, leaving more to flow into the lake.

Despite that, Garrett says, “Mono Lake is not at the healthy management level.”

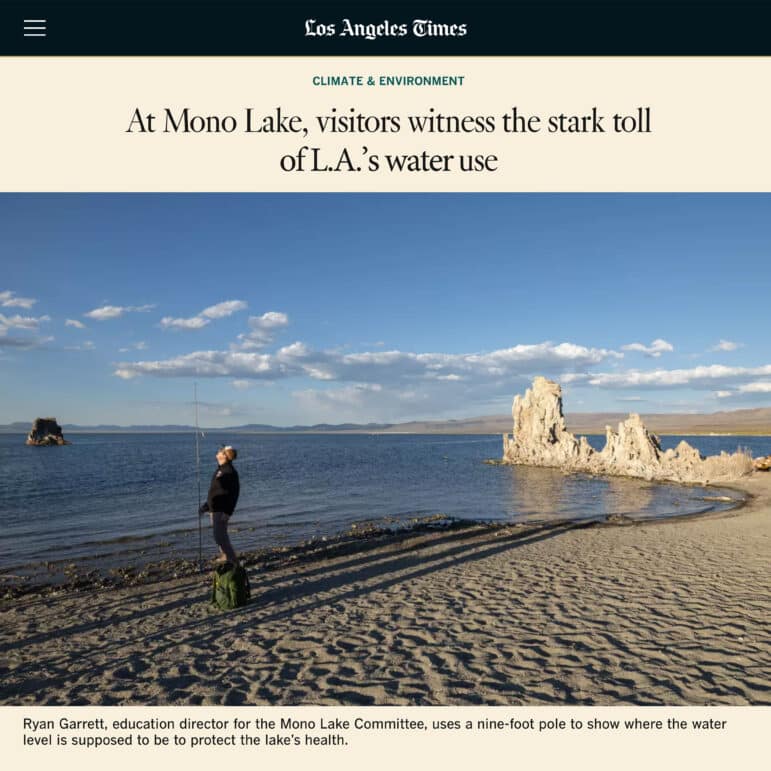

He opens his backpack and takes out a collapsible metal pole, extending it 9 feet.

He stands it vertically on the sand to show the lake is still far below the target level agreed on 31 years ago.

“So, the question now becomes, is Mono Lake doomed?” he says. “Is this the highest it can get? No, absolutely not.”

Garrett notes that conservation efforts in L.A. have significantly reduced water use over the last three decades.

The 1994 decision included a backstop: If the lake level doesn’t rise enough, the State Water Resources Control Board is to hold a hearing to determine if the rules need to change — an assessment that both environmental advocates and the DWP’s managers say they hope will happen soon.

“What’s super, super exciting is that hearing is right around the corner,” Garrett says. “So right now is the best time to learn about Mono Lake, because the next great effort to save Mono Lake is about to begin.”

Ian James sums it up well—both the urgency of the ecological situation and the growing public recognition that Mono Lake continues to get the short end of the stick as the Los Angeles Department of Water & Power chooses to maximize water diversions that prevent the lake from rising to the healthy level mandated by the State Water Board in 1994.

The State Water Board is long overdue in holding its planned hearing to review and modify the diversion rules it set to allow Mono Lake to rise to the healthy management level, which will protect numerous Public Trust resources, including ecological health, air quality, scenic and Tribal resources, and unique, internationally significant habitat for millions of migratory and nesting birds.

As the article describes, the unhealthy lake level situation at Mono Lake often comes as a surprise. But, the Mono Lake story is nothing if not a story of hope, and the next great effort to save Mono Lake is underway.

And sure enough…

As the tour ends, Jerardo Reyes, a roofing contractor from Rialto, says he hadn’t known about Mono Lake and came away wanting to learn more about the places Southern California gets its water.

He and his wife Jeannette had stopped to see the lake with their four children.

Reyes says he believes that while L.A. needs water, the lake also needs it, and “you’ve got to find a balance.”

“It’s a beautiful lake,” Reyes says. “I hope this lake is here for my kids to see, and my grandkids to see, in the future.”

Take a South Tufa tour

The Mono Lake Committee, California State Parks, and Inyo National Forest give upwards of 800 free South Tufa tours annually, reaching thousands of people right down at the lakeshore. You can sign up for a tour here, or, if you can’t make a tour, there is a free self-guided version here.

Top photo by Andrew Youssef.