Jen Bayer is an independent scientist with the Silicon Valley Barcode of Life project, which engages people in learning why biodiversity is important to human well-being. Jen stayed at the Mono Basin Field Station this past summer to study arthropod biodiversity here and offered the following description of her fascinating work.

Many people come to the Mono Basin to research hydrology, ornithology, botany, and geology. I’m here to study arthropod biodiversity, and to promote its conservation.

Arthropods

Arthropods are one of the most numerous and diverse multicellular life forms on Earth, constituting an estimated five of every six known animal species. About a million arthropod species have been described, and conservation biologists estimate that millions more await description. Insects alone represent more than half of all known multicellular terrestrial species. Their total biomass is larger than that of any other class of terrestrial animals.

Wherever arthropods occur—and they are ubiquitous—they perform critically important ecosystem functions as decomposers, pollinators, prey for other species, and primary and secondary consumers. Their ecosystem services are worth an estimated eight billion dollars to US agriculture annually. Because of their diverse central roles in ecosystems, arthropods are useful indicator species.

Biodiversity crisis

Around the world, populations of organisms are being depleted and species driven to extinction at rates several times those which have prevailed since a meteorite impact ended the reign of the dinosaurs 56 million years ago. This bioannihilation is only the seventh event of its kind known to have occurred in the nearly four billion years since life appeared on Earth.

I grew up exploring the Santa Cruz Mountains, volunteering with an oak habitat stewardship project on Stanford University lands, and hiking the Sierra Nevada backcountry. Seeing the nature I loved disappearing before my eyes, I want to defend it. Three years ago my twin sister and I founded Silicon Valley Barcode of Life (SVBOL). We use DNA Barcoding to engage people in learning about the importance of biodiversity and in acting to protect it.

DNA barcoding

DNA barcoding is a means to quickly, accurately, and inexpensively create a unique identifier, similar to a barcode on a grocery store item, for any species. DNA barcodes are generated by extracting a short specific piece of DNA from a tissue sample and “reading” it. With barcodes we can often precisely identify an organism of a described species, and we can identify near relatives of organisms whose species have yet to be described.

When the opportunity came up to take what I’ve learned through SVBOL and contribute to the Mono Lake Committee’s mission of protecting and restoring the Mono Basin ecosystem and educating the public about Mono Lake, I gratefully accepted.

I’m aiming to demonstrate how DNA barcoding can be a way to quickly and cost-effectively catalog biodiversity in the Mono Basin and thereby contribute to global and local biodiversity libraries and provide a resource on which others can rely to inform science-based stewardship and enrich educational program participants’ and other visitors’ experiences.

Arthropod catalog

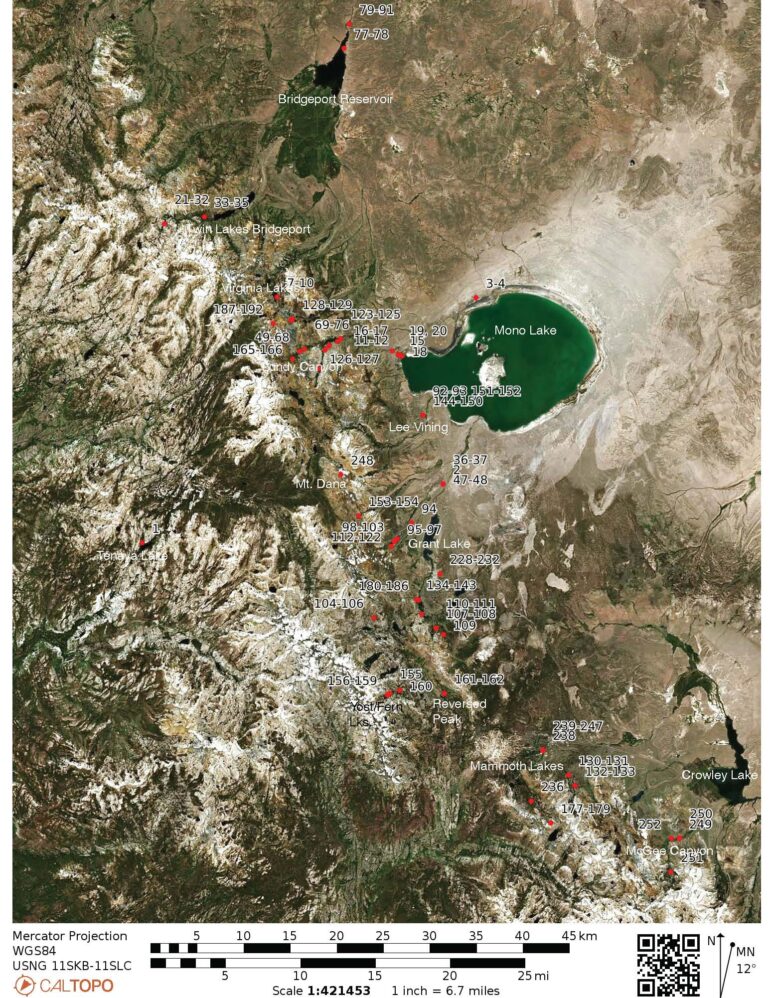

After a brief exploratory collection in September 2020, I returned in June 2021. I’ve collected by hand and with an aerial net in locations ranging from Bridgeport to Mammoth Lakes. In addition, I’ve deployed pit traps for several-day periods on the grounds of the Mono Basin Field Station in Lee Vining, and a malaise trap on the grounds of the Mono Lake Committee Outdoor Education Center.

I’ve now hand-collected 250 unique Mono Basin specimens and gathered several thousand more—likely many of the same species—with the malaise trap. These include representatives of the following classes and orders: Araneae (21), Coleoptera (17), Cicadellidae (9), Diptera (36), Formicidae (12), Hemiptera (6), Hymenoptera (16), Lepidoptera (15), Neuroptera (1), Orthoptera (5), Raphidioptera (2), and Scorpiones (1).

For each hand-collected specimen, I record a description of the collection location including GPS coordinates. Then, I chill each in a freezer for a few hours to immobilize it, photograph it, preserve it in ethanol, and supplement my time and place of collection data with a taxonomic description based upon the arthropod section of the Laws Field Guide to the Sierra Nevada and upon what I learned through my pilot collection in September 2020.

After I’ve finished collecting for this season, I’ll sample tissue from each specimen—part of a leg or an antennae from larger specimens, the entirety of the very small ones—place each sample in a separate well of a standard 96-well microplate used in DNA sequencing, and ship my samples to the Canadian Centre for DNA Barcoding (CCDB) at the University of Guelph in Ontario, Canada.

CCDB will generate a DNA barcode for each specimen, and upload these and associated data to BOLD Systems, a publicly accessible database currently containing over nine million barcode records and used by people around the world to catalog biodiversity and monitor changes to it.

How you can help

If you’re interested in lending a hand with fieldwork, macrophotography, graphic design of reports, entomological expertise, or access to audiences receptive to learning about protecting biodiversity, please let me know. I’m also looking for funds to defray the costs of DNA sequencing at CCDB. SVBOL, which sponsors my work in the Mono Basin, is an all-volunteer endeavor made possible by dedicated collectors, advisors, and donors. You can email me for more information.

Photos courtesy of Jen Bayer.