Thursday was my last day in the field before a well-advertised storm was to drop 1–3 feet of snow in the Mono Basin. As I drove down to Rush Creek, the winds were picking up, snow was blowing off Sierra peaks, and lenticular clouds graced the late-afternoon skies.

The Los Angeles Department of Water & Power (DWP) had just lowered the flows in Rush Creek and Lee Vining Creek, and I was checking to see if certain side channels were still flowing, as well as checking on a few other things before the expected deep snow made travel to the streams difficult.

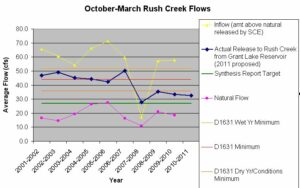

The flow change was recommended by the stream scientists in charge of the restoration, and approved by the State Water Resources Control Board. Lower winter flows are more in line with the natural flow pattern in the Mono Basin, and are expected to allow fish to expend less energy fighting the current during the winter. You can read more about this in the Synthesis Report in our Streamflow Center. This is the fourth winter in a row that flows below the dry-year minimum (ordered in Decision 1631 in 1994 by the State Water Board) have been released down Rush Creek. The graph below shows the average October–March flow; in 2010–2011, for example, the flow release will be close to the recommended 27 cubic feet per second (cfs) starting this week, but higher flows in October and the first half of November bring the average up to 33 cfs. Since Grant Lake Reservoir is high, it is likely that it will spill by April, bringing the average up even further.

When I reached Rush Creek, I was surprised to see the 8 Channel and the 4bii Channel flowing. These side channels were opened up a few years ago in order to improve groundwater and vegetation conditions on the floodplain. They both dried up after this year’s peak flow, and both required some work on the entrances in August in order to get flow back into them. Now the flow in the creek was 42 cfs, the lowest since the peak flow, and the upper portions of both channels were still flowing. We had the rainiest October on record, and perhaps that was helping.

After I left those channels, I headed downstream—to where we planted Jeffrey pine seedlings in 1996 in a partnership with TreePeople, an LA-based nonprofit. TreePeople had grown them in containers that summer, and we planted them on Restoration Days, a September event that the Committee held during the late 1990s.

Recently, I had been noticing that most of these pines are now big enough to be visible above the willows and young cottonwoods along this part of Rush Creek. Especially now, after the other trees had lost their leaves, most of these 14-year-old pines would be easy to spot. Why did I want to find them? I wanted to update our survival count (found on the Mono Basin Clearinghouse Website). Our last survival count on these trees was in 1998, when 44 of the 91 planted trees were still surviving. Today’s results: 37 surviving! 27 trees died the first year, 20 trees died the next year, and only seven trees died in the last twelve years!

It was a good memory exercise—to remember where we planted them, and where I had led groups all that fall and the following summer to water them. I started at a little island—no longer an island—where Matt Moule, our Outdoor Experiences Coordinator at the time, had bet me none would survive. He was right—none of those on that island had survived the first two years. But I checked it today anyway, just in case one was hiding in the grass or willows, and was now tall enough to see. No such luck.

As I headed upstream, I reached a group of pines that I have seen often in recent years. They are clearly growing at rates dependent on competition from surrounding plants, with the one by itself on the left the tallest and the one surrounded by other trees on the right the smallest (see photo below).

A cluster of 13 pines just upstream from these was the largest congregation of surviving trees, and was growing in a really good site—a low gravel bar with good soil and water conditions. Most of these were taller than the ones in the photo, and often they had a much smaller pine growing among their branches. Because it was such a good site, we planted the trees closer together here, and the “doubles” were ones we had only planted 2–3 feet apart.

Across the main channel from here were a few pines that I hadn’t remembered planting over there. Were they part of the planting or not? I didn’t remember them well because Matt or I would cross the channel to water them while the rest of the volunteers would keep their feet dry and not cross the channel. After investigating each one, I determined that they were part of our 1996 cohort. They were all the same age, and there were no other young Jeffrey Pines in the area of any age. In fact, almost every Jeffrey Pine tree in the Rush Creek bottomlands less than 20 feet tall seems to be one that we’ve planted! I’ve often seen lodgepole pines, which tolerate wetter soils, colonizing the floodplains of both Rush and Lee Vining creeks—but rarely Jeffrey pines.

One of these pines across the channel will die soon because it is getting flooded by Channel 10. Channel 10 is a side channel that was rewatered in the fall of 1995. In the spring of 1996, we planted pines and other trees along that Channel, about four months before we planted these. Channel 10 has been a magnificent success, and you can see a report on its rewatering, complete with before and after photos, on the Mono Basin Clearinghouse Website. The lower end of Channel 10 spreads out and returns to the main channel in several small waterfalls (due to the incision of the main channel during the time Channel 10 was dry). These deltaic channels have themselves incised, creating an incredibly complex habitat out of what was initially a large pond immediately after its rewatering. One of our pines is getting flooded in this area and will probably not be around for our next survival count.

Are we happy with the 41% survival of our 1996 Jeffrey pines in this area? Incredibly. These 37 trees are adding structure and diversity to an area where there are few pine trees growing. PRBO Conservation Science found that the presence of pines in a riparian area add to bird diversity, however when pines dominate, bird diversity decreases. Getting the balance right is important.

The State Water Board ordered the planting of Jeffrey pines because they are slower to colonize than other species. The dewatering of Rush Creek for decades wiped almost all of them out, as attested to by the numerous large pine logs hidden in the sagebrush. Planting them gets us back to a more natural condition more quickly. Large woody debris, such as that provided by Jeffrey pines when they die and fall in the creek, is an important component of a complex stream system. Thanks to our planting program—not to mention the rewatering of side channels such as Channel 10—this reach of Rush Creek is a bit closer to what would naturally be there.