By now, nearly everyone has heard that California is suffering from record-setting drought. After four consecutive years of below-normal precipitation and above-normal temperatures, the state is reeling. Every watershed in California is stressed, a mandatory 25% water reduction is in effect for residents, urban areas have begun rationing supplies, over half a million acres of agricultural land are fallowed, fish species are nearing extinction, millions of trees in the Sierra are dying from drought-related stress, and fire danger is extreme. Water levels in lakes and reservoirs around the state are well-below normal. The Mono Basin is also suffering from extraordinary drought.

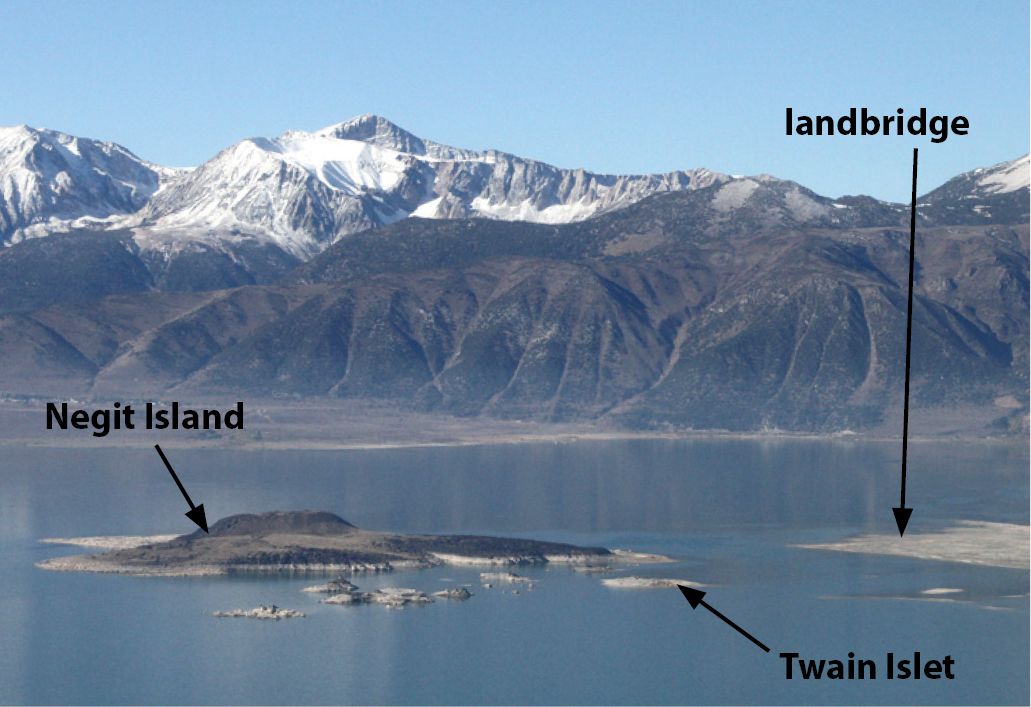

Four dry years have depressed Mono Lake five feet in elevation and the lake is expected to lose around two feet this year. The cumulative impacts of drought and increasing temperatures are significant. Lake salinity is on the increase, the growing landbridge between Negit Island and the mainland threatens nesting California Gulls, and new alkali flats pose an increasing threat to air quality and human health. Increasing winter and spring temperatures may be changing the productivity and timing of the brine shrimp (Artemia monica) population. A shift in Artemia timing is, in turn, creating difficult consequences for the one million plus Eared Grebes that rely on shrimp for food during fall migration. In addition, reduced flows in Rush Creek mean warmer water temperatures, increased turbidity, and potential peril for the creek’s trout population.

Advancing landbridge

The most visible change due to the drought at Mono Lake is the landbridge threatening to connect Negit Island with the north shore. The retreating lake has exposed shallow lakebottom and tufa shoals, making it possible to approach Negit and its satellite islets by foot. These islands harbor a significant California Gull colony, along with a handful of nesting Black-crowned Night Herons and Caspian Terns. At the current lake elevation, coyotes can explore the landbridge and easily see these birds. If enough coyotes learn to wade or swim to nearby islets, they would be rewarded with helpless eggs or chicks, disrupting nesting birds on Negit or any other islet. Today the lake is just four feet above a complete connection with Negit. Twain Islet, adjacent to Negit Island, is home to 46% of the nesting California Gull population at Mono Lake. If the drought continues beyond this year, other nesting sites like Twain will be threatened by predation resulting from the exposed landbridge.

Declining air quality

Among the reasons for maintaining a higher lake level are human health and federal air quality regulations. Air quality declines with the lake level. Newly-exposed lakebottom is a source for salt and other minerals that take flight during windy days. The particulate matter (PM-10) produced by these alkali flats is very small, ten microns or less in diameter (human hair is 90 microns wide) and is easily inhaled deep into the lungs, causing respiratory problems.

The California State Water Resources Control Board recognized that air quality was an important consideration for increasing the level of Mono Lake, and that excessive water diversions created the problem to begin with. The State Water Board determined that the management level of 6392 feet above sea level would be the elevation at which most of the dust-producing areas would be submerged. Today, as expected, we are seeing significant dust storms now that Mono Lake is lower. The Great Basin Unified Air Pollution Control District continues to monitor air quality in the Mono Basin and quantifies the impact of individual and cumulative dust events. You can see real-time data online here.

Not the good ol’ days

Large dust storms and the landbridge are reminiscent of Mono Lake in the years of excessive water diversions, before the 1994 State Water Board decision. No one likes to see the lake drop this low again, especially after its general course of upward momentum over the last 17 years.

Fortunately, when the State Water Board issued their 1994 decision for Mono Lake, they created a framework for balancing water diversions with lake levels tied to ecological health, air quality, and recreational values. Now, for the first time since this decision, the lake has declined below an important threshold, triggering a significant reduction in export to Los Angeles.

6380′: Health insurance for Mono Lake

On April 1, 2015, Mono Lake Committee staff cooperatively measured the lake level with Los Angeles Department of Water & Power (DWP) staff from Bishop. On that day the lake level gauge showed 6379.01 feet in elevation, and it was no surprise. Because Mono Lake fell below 6380′ exports are now significantly reduced until the lake rises to, or above, 6380′ on a future April 1. The reduction in diversions will mitigate difficult drought conditions at the lake and put it in a better position to recover when wet winters return to California.

How much water are we looking at? This year, DWP’s Mono Basin exports were reduced from 16,000 acre-feet of water to 4,500 acre-feet. An acre-foot (af) of water is approximately 326,000 gallons, and enough to supply the water needs of ten people in Los Angeles for a year (based on the most recent five years of water use data). The export difference, 11,500 af, is significant in a drought, but it’s not critical. This amount of water equates to a 1.8% reduction in Los Angeles’ overall supply. The city is already making up for the loss of supply through aggressive water conservation goals while continuing to implement water recycling and other strategies that better cope with future reductions in water supplies due to drought and climate change.

Just add water (and pay close attention)

How far can Mono Lake keep dropping? We know that the lake will drop around two feet this year. In a year with record-low snowpack, there is little water remaining to make its way to Mono Lake. The next important lake level is 6377 feet. If at any point Mono Lake drops below, or is projected to drop below 6377′, no diversions are allowed. The 6377′ rule has never been triggered before, and the Committee is actively monitoring Mono Basin hydrology and projecting future lake levels to determine if, and how, it will come into effect.

Right now, in the Mono Basin, as in all of California, we are in uncharted territory. We have never experienced the impacts of extremely dry years combined with record warm temperatures. While watersheds all over the state are suffering, fortunately for the Mono Basin, we have a history of advocacy, science, successful legal action, and careful planning that continue to protect and balance Mono Lake’s public trust values, even in times of drought.

Climate change vs. Mono Lake

California has the most variable precipitation regime in the continental US, but it’s clear that anthropogenic climate change is making that variability more extreme. In 2014 we had the warmest year in history by an alarming margin, and the last two consecutive winters in California have been the warmest in history. These conditions have easily transformed a string of dry years into the most severe drought in the state’s history. Looking at 120 years of statewide temperature data, the warming trend is conclusive and sobering.

Changes in future precipitation are less certain. Extreme drought year types are expected to increase in frequency, along with more extreme rain and flooding connected to atmospheric river events. Decreasing Sierra snowpack and earlier spring runoff are already measurable. This year’s Sierra Nevada snowpack was 5% of average, the smallest in history.

Since 1941, Los Angeles has diverted a total of 4.28 million acre-feet of water from the Mono Basin. If these diversions had never occurred, Mono Lake would be 37 feet higher than it is today, and would be in much better shape to weather this drought. More than just interesting speculation, it puts Mono Lake’s condition in perspective. Protection and restoration plans are currently in place that address the problem of the last century—excessive water diversions. But are they capable of adapting to human-caused climate change—the greatest challenge of this century?

The consequences of climate change are large, complex, and affect us all. The Mono Lake Committee is asking questions and seeking answers in terms of what this change means for the Mono Basin. As a group of concerned citizens who care about the lake and streams, it is our mission to figure out what lies ahead for Mono Lake.

This post was also published as an article in the Summer 2015 Mono Lake Newsletter.

what is the feasibility of constructing a wildlife fence across the land bridge and down into the water a considerable distance on either side of it? Well this would be a rather visible human intervention in an otherwise untouched scene, this would give the gull colonies a better chance of survival should the lake continue to drop, as it is projected to do.