DWP stream diversions will undo this year’s lake level gains unless State Water Board acts

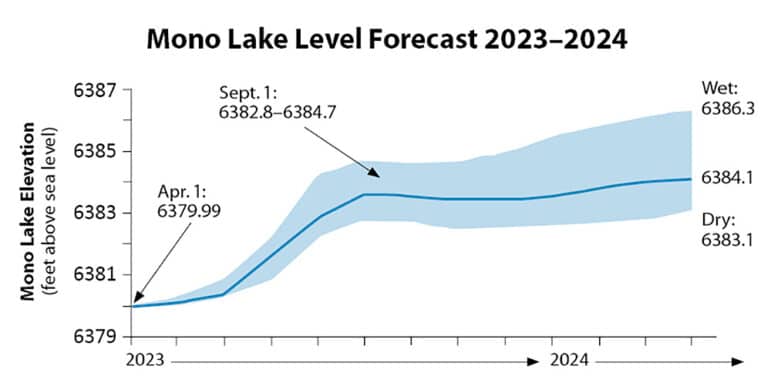

The incredibly wet winter of 2023 has us anticipating an exciting 5½-foot rise in Mono Lake’s level by fall. That gain will boost the lake 30% of the way to the mandated healthy level that will protect the lake, its ecosystem and wildlife, air quality, cultural resources, and more.

But this important progress toward the long-overdue management level will be lost if stream diversions by the Los Angeles Department of Water & Power (DWP) continue unchanged.

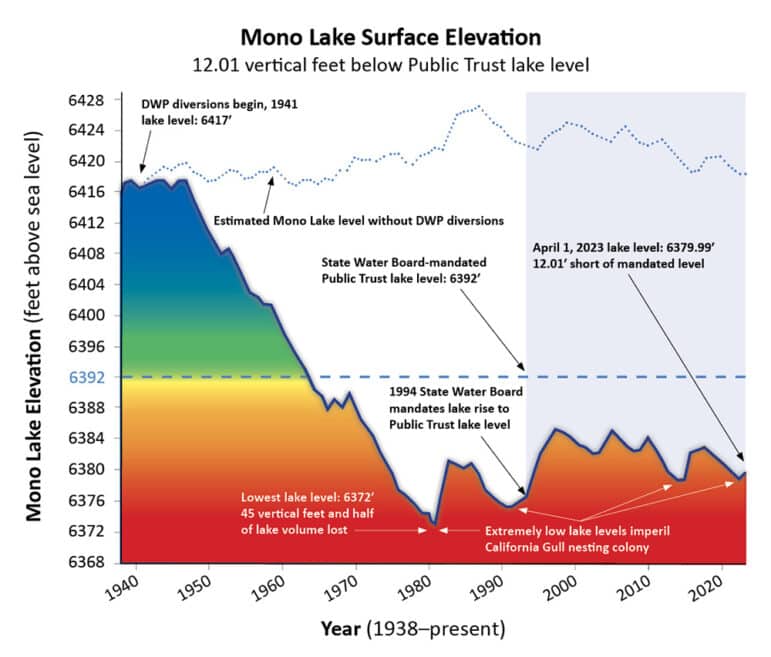

In short, one wet year is not a management plan, nor a remedy to the inadequacies of the now outdated rules the California State Water Resources Control Board established to raise the lake to the Public Trust lake level of 6392 feet above sea level by 2014. With the lake a decade late and a dozen feet short of reaching that critical level, State Water Board action is urgently needed to lock in the gains Mono Lake will see this year and keep it on a rising trajectory.

Without Board action, DWP water diversions will, year after year, undercut the lake rises of wet years and accentuate the declines in the future droughts that we all know lie ahead. Mono Lake Committee hydrologic model projections show that continuing to follow the outdated rules will prevent the lake from achieving the Public Trust lake level.

Simply put, if DWP keeps doing the same thing it has done for the past three decades, there’s no reason to expect different results. Plus, with the outdated rules set to allow stream diversions to quadruple in 2024, it is time for action.

Outdated rules will cause lake rise to be lost

The State Water Board established stream diversion rules back in 1994. Their purpose was to implement the protection of Mono Lake by raising the lake to the healthy Public Trust lake level in 20 years while allowing limited diversions of water to Los Angeles along the way. Although they were based on solid analysis at the time, the rules have not delivered the intended result. The lake is a decade overdue and only 30% of the way to the mandate; meanwhile, DWP has diverted the maximum allowed every year, taking more water than expected and continuing to divert even now despite the lake’s lack of progress.

So what will happen to this year’s 5½ feet of lake level gain in subsequent years? If diversions continue under the outdated rules, the gains will be lost.

One clear illustration of this is to look at recent history. As the Committee told the State Water Board at the recent workshop on Mono Lake, we’ve seen this movie before, and we know how it ends.

Six years ago, the lake rose more than four feet thanks to the wet winter of 2017. Unfortunately, with DWP diverting the maximum allowed each year, the gains of 2017 were erased by 2022, triggering two emergency situations: Salinity increased to levels that violated federal and state water quality regulations, and the landbridge was exposed enough to allow predators access to the California Gull nesting islands.

The problem is that DWP water diversions hold back the lake when it is rising and accelerate its drop when it is falling. Looking to the future, droughts are to be expected, and in the era of climate change their intensity, frequency, and duration are increasing. The key to lake health is what position Mono Lake is in when the inevitable dry years return.

If diversions continue unchanged, gains will be lost

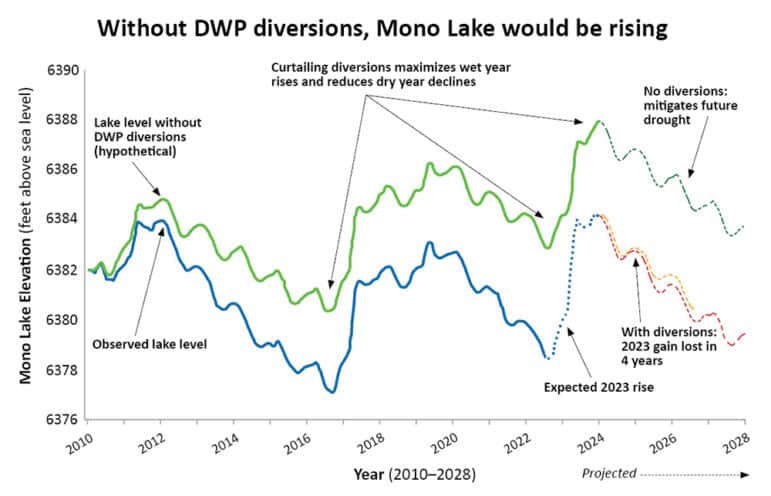

The Committee has taken a look back at the time period since 2010, which includes a moderate wet year, two extreme wet years, and the significant drought of 2012–2015 as well as the recent 2020–2022 drought. This time period is a good one for looking at the benefits of maximizing wet year gains as insurance against dry year declines. It is also representative of the developing whiplash pattern under climate change, in which annual precipitation swings from dry extremes to wet and back again.

The Committee hydrology team analyzed a key question: What happens to Mono Lake if one of the two recent droughts repeats itself starting next year? The answer is worrisome.

With the outdated stream diversion rules in place, a repeat of these droughts is amplified by DWP diversions continuing. The takeaway: Under the outdated rules, the 5½ feet we expect Mono Lake to rise in 2023 could be gone in as few as four years.

The hydrologic projections underscore a point the Committee and partners have been making frequently: After 29 years, it is clear the lake level rules aren’t working, and it is also clear the State Water Board has to fix them. Relying on one wet winter’s precipitation is not a plan—for Mono Lake nor Los Angeles. Allowing the current outdated stream diversion rules to continue ensures that Mono Lake’s rise in 2023 will only be temporary.

Without DWP diversions Mono Lake’s rise would be preserved

The modeling team also asked: What would have happened if stream diversions had stopped in 2010—and everything else happened as it did? The answers are instructive.

First, this modeling shows that the lake, absent DWP diversions, would on average be rising—even accounting for the two driest three-year periods on record. Mono Lake would be four feet higher today, poised to hit the 6388-foot mark by early 2024. This illustrates the simple principle that the impact of stream diversions on the lake’s level adds up over the years to significant amounts.

Second, the modeling shows that curtailing diversions maximizes wet year rises and reduces dry year drops, allowing the lake to build a critical buffer against drought. In this scenario, the lake would likely have remained above the 6380-foot level during both recent droughts, meaning that the California Gull protection fence would not have been necessary and salinity violations would have been avoided.

Third, in this hypothetical scenario, a future repeat of the 2012–2015 drought does cause the lake to fall, but it remains above 6383 feet (see dashed green line in graph above).

Of course, the lake needs to be higher than 6380 or 6384 or even 6388 feet to provide protection and health for all the resources the State Water Board evaluated, including California Gulls, air quality, salinity levels, and more. That was the plan the Board ordered back in 1994—raise the lake to the 6392-foot Public Trust level to restore ecological health through wet years and dry ones.

Better rules can better protect the lake

Hydrology modeling shows we can do much better for the lake. Both Mono Lake Committee and California Department of Fish & Wildlife analyses show that different implementation rules would have produced notably different results for Mono Lake. For example, if the State Water Board had suspended diversions in 1994 until the protection level had been achieved, the lake today would be significantly higher and, after this incredible winter, expected to approach 6390 feet in 2024, putting it within quick reach of the Public Trust lake level.

DWP has argued that its water diversions have little impact on Mono Lake. Analysis of the actual hydrology shows otherwise.

Water in Los Angeles

In the big picture, Los Angeles and Mono Lake share a problem: both need an adequate and reliable water supply. The challenge is to achieve solutions, and the Committee sees flexible and innovative paths forward. Indeed, Los Angeles has set impressive goals for sustainable local water supply development (see page 9) that will reduce the burden on places like Mono Lake. Funding for projects like conservation, turf replacement, and stormwater capture can accelerate this good work. The Committee is working with Los Angeles community groups and state officials to advance project concepts to provide the flexibility needed to deliver the water to Mono Lake that it needs while meeting real water needs in Los Angeles.

State Water Board action is essential

Earlier this year, the Mono Lake Committee, California Department of Fish & Wildlife, and Mono Lake Kootzaduka’a Tribe asked the State Water Board to take swift action to implement the Mono Lake protection requirements of their 1994 decision—specifically, to temporarily suspend diversions by DWP to allow the lake to reach and fluctuate at the Public Trust lake level. Joined by more than 3,000 supportive public commenters, including air quality and land management agencies and Mono County, the Committee asked the Board to hold the hearing it has already determined is necessary to look into changing the outdated diversion rules this year. Given the narrow scope of such a hearing, which would only need to address how to expeditiously implement the 6392-foot Public Trust lake level, we believe the Board has access to the data and established hydrologic models it needs to proceed quickly.

As record Mono Basin snowfall turns to record runoff , the pressure for a State Water Board hearing is also at record levels. The extremely wet winter of 2023 is a gift that will raise the lake multiple feet toward the Public Trust lake level in a single season. The fact is clear that, if given the opportunity by the Board, Mono Lake will rise. That gives us a rare opportunity to seize the moment to preserve this year’s lake level gains before DWP diversions increase and, once again, undercut progress in protecting Mono Lake.

Tufa towers toppling

Mono Lake’s tufa towers are vulnerable to toppling when storm waves erode their bases. The repeated rise and fall of the lake creates a repeated risk of toppling, which underscores the importance of preserving this year’s lake rise and continuing upward to the 6392-foot Public Trust lake level.

Dust storms will continue despite lake rise

Winter snow is excellent at suppressing dust when it blankets the lakebed that was exposed by DWP water diversions. That exposed dust-emitting land is often responsible for the worst PM-10 particulate air pollution in the nation. After this year’s snow melted in April, dust storms immediately kicked up again as expected—with two exceedances of Clean Air Act health standards recorded in the first two weeks of May alone. Detailed air quality monitoring shows decades of significant violations of the health standard, including 24 high-concentration exceedances last year.

As Mono Lake rises it will inundate the dusty lakebed, but this year’s rise will still leave thousands of acres of lakebed exposed—far less than is needed to solve the air quality problem at Mono Lake. To do that the lake must rise to the Public Trust lake level, which was selected in part to ensure that hazardous dust storms come to an end.

Meromixis expected this year

The welcome rise of Mono Lake this year is expected to produce a less desirable, though temporary, side effect. The large influx of fresh water from the streams will produce a phenomenon known as meromixis, in which a fresher (though still salty) layer of water floats on top of the more saline lake water and prevents the lake from fully mixing. By trapping nutrients under the fresher layer, meromixis reduces the food supply available to brine shrimp and can cause a decrease in productivity, which affects available food for some species of birds. The impact, however, is transient and will disappear as the lake’s water mixes more fully over subsequent years.

Meromixis is more likely to occur when the lake level is low, like it is now, because low levels cause excessively high salinity levels. The higher the lake level, the lower the salinity, and the easier it is for lake water and fresh inflow to mix. The State Water Board determined that the probability of meromixis is very low when the lake is at the 6392-foot Public Trust lake level—yet another reason that taking action to ensure a quick, steady rise is the right thing to do for the health of Mono Lake.

This post was also published as an article in the Summer 2023 Mono Lake Newsletter. Top photo by Elin Ljung.