As Mono Lake rose nearly five vertical feet this year, visitors and residents in the Mono Basin marveled at Mono Lake’s fast-changing shoreline. Driving along Highway 395, we witnessed a peninsula become an island at Old Marina. Osprey nests built on land-locked tufa at South Tufa are again protected by watery moats. Long-dry brackish and freshwater lagoons along the north and east shores resurfaced. The surface area of the lake has increased more than four and a half square miles, shrinking the landbridge and increasing the distance between predatory coyotes and California Gull nesting grounds.

The lake rise is cause for celebration and began at a time when the lake level was dangerously low. Unfortunately, the achievement comes with a downside: under current rules a rising lake allows the Los Angeles Department of Water & Power (DWP) to increase diversions from Mono Basin streams. In April 2024, the lake’s elevation will be well above the 6380-foot threshold at which DWP’s allowance will nearly quadruple to 16,000 acre-feet. By contrast, this year’s export allowance is 4,500 acre-feet because Mono Lake’s elevation was a hair below that threshold on April 1, 2023.

The coming winter will determine whether the lake resumes its rise or if this summer’s high point is just one more peak in the ups and downs Mono Lake has experienced since the California State Water Resources Control Board issued Decision 1631 in 1994. This decision modified DWP’s water rights in the Mono Basin with the mandate requiring the lake to reach the ecologically healthy level of 6392 feet above sea level—the Public Trust lake level.

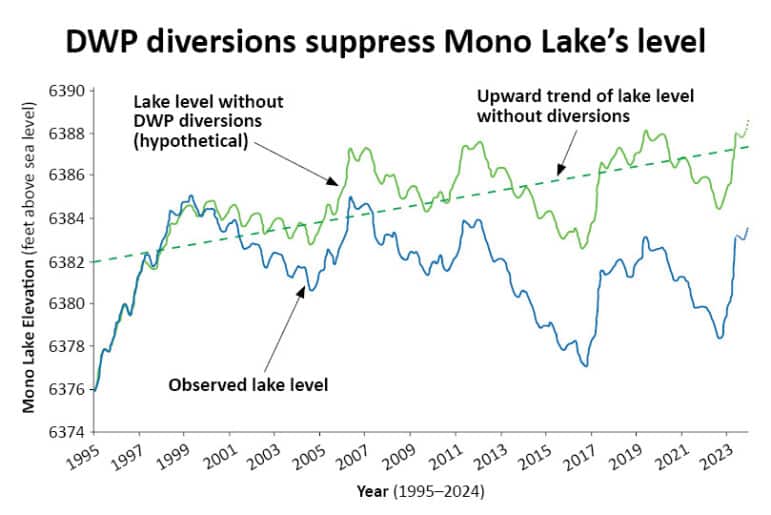

While year-to-year variability in runoff is the main determinant of lake level fluctuations, DWP’s stream diversions have, year-by-year, prevented Mono Lake from rising to the Public Trust lake level. In a wet year, diversions eat into the lake rise; in a dry year, diversions exacerbate the lake’s fall. Since Decision 1631, DWP has exported 375,000 acre-feet of streamflow—enough water to raise Mono Lake’s elevation by more than five feet.

DWP has received 16,000 acre-feet—more than five billion gallons—of Mono Lake streamwater in 22 of the 29 years since Decision 1631. This steady export of Mono Lake’s inflow has suppressed Mono Lake’s rise and the lake’s elevation has fluctuated around 6382 feet for nearly 30 years. By contrast, if the State Water Board had paused DWP’s stream diversions in 1994, Mono Lake would have left the 6382-foot elevation behind in the late 1990s. Mono Lake levels would have naturally fluctuated in response to wet and dry years, but the average elevation would be steadily rising. This year’s epic five-foot rise would have placed Mono Lake’s elevation around 6389 feet, within reach of the Public Trust lake level.

If DWP were to pause stream diversions from the Mono Basin, it would continue to receive approximately 10,000 acre-feet of groundwater diversions from the Mono Craters Tunnel each year. So even with a pause in stream diversions to allow Mono Lake to achieve the mandated Public Trust lake level, Los Angeles would still receive a consistent delivery of water through the LA Aqueduct in the Mono Basin.

This post was also published as an article in the Fall 2023 Mono Lake Newsletter. Top photo by Elin Ljung.

Very good article. The tunnel reference is most important.