Stream diversions holding back lake rise

On the wall of the Mono Lake Committee Information Center & Bookstore is a vertical blue tube representing Mono Lake’s level, with a yellow sliding arrow pointing to the present-day surface elevation. It is one of the first things visitors inspect because it answers the popular question; how’s the lake doing?

We installed the display fifteen years ago and expected that, in the majority of years, we’d be bumping that display arrow upward to track the lake’s rising journey of recovery to the hard-won, state-mandated, ecologically sound level of 6392 feet above sea level.

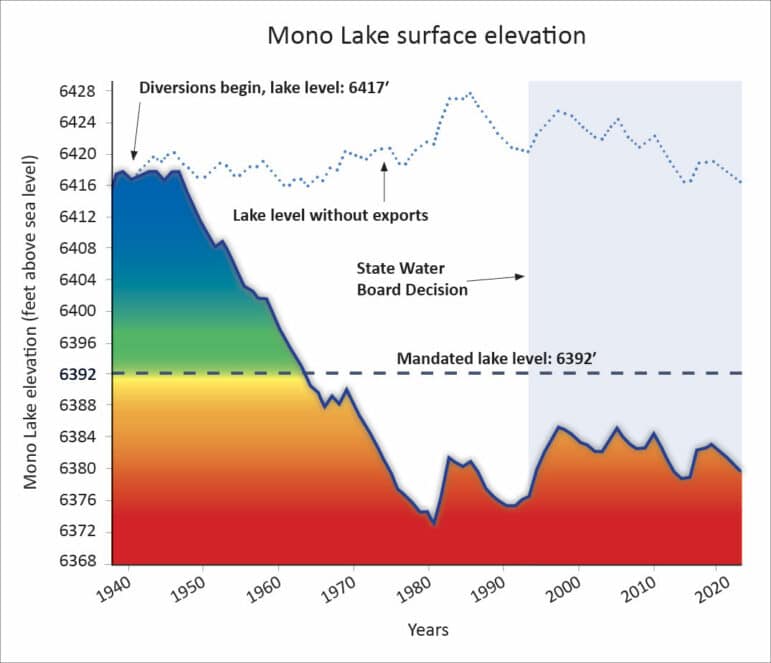

Raising Mono Lake, however, has not gone according to plan. As drier conditions settle on the West, amplified by climate change, we often have been pushing that arrow lower, tracking the lake’s decline. Today, years after it was expected to return to the required healthy level, the lake is only 30% of the way there.

The lack of progress has motivated the Mono Lake Committee to undertake a multi-year project to update the most comprehensive water balance model of Mono Lake so that we can evaluate the causes—and consider the role of stream diversions by the Los Angeles Department of Water & Power (DWP)—in slowing Mono Lake’s return to health.

Lake not rising on schedule

In 1994, nearly 30 years ago now, the California State Water Resources Control Board issued its landmark water rights decision after extensively reviewing the tremendous impacts of tributary stream diversions by DWP. Those excessive diversions began back in 1941 and dried up the streams, imposing the equivalent of a vast drought on the lake for decades. As a result, Mono Lake fell more than 45 vertical feet, lost half its volume, doubled in salinity, and motivated a citizen-driven protection effort led by the Mono Lake Committee.

The State Water Board required that Mono Lake rise 17 feet to protect the lake’s unique and valuable public trust resources for current and future generations, including returning the lake to ecological health, protecting habitat for millions of migratory and nesting birds, submerging dusty exposed lakebed, and restoring tributary streams. The decision also set forth rules, derived from modeling projections, allowing DWP to continue stream diversions at a volume compatible with raising the lake.

The momentous recovery mandated by the State Water Board got off to a strong start with four wet winters that promptly caused a ten-foot increase in Mono Lake’s level. The prescribed healthy level seemed easily within reach as the new century arrived, but the 2000s had many more dry years than wet ones and the lake ended the decade several feet lower than it started.

While some rise and fall of Mono Lake is to be expected in response to wet and dry years, all the celebrants of the State Water Board decision, including the Committee and Los Angeles leaders, expected an upward trend that would deliver the lake to its healthy long-term management level in a reasonable amount of time. In particular, the State Water Board expected the journey to take 20 years and made provision for a hearing if the lake rise wasn’t accomplished by 2014.

But as 2014 approached, even a glance at the lake level graph raised questions about whether the lake’s recovery was on track (see graph in yellow box below). With virtually no possibility of fulfilling the State Water Board’s expectation, an extension was agreed to in hopes of seeing the planned rise complete by 2020. Five years of drought instead dropped the lake a shocking seven vertical feet. The wet winter of 2017 delivered a welcome lake rise, but 2020 came and went with the lake far short of the goal, triggering the hearing requirement.

These days a glance at the lake level graph raises alarm. The lake sits 12 feet below the mandated sustainable level—after nearly 30 years it is just 30% of the way to the level required for protection. And with continuing drought it will fall further.

At low levels like this, the situation is perilous because the lake has no buffer left to absorb dry year drops. Already, on windy days, dust is blown off the exposed lakebed, creating the nation’s worst PM10 particulate air pollution. As the lake falls farther, predators will gain access to critical California Gull nesting grounds, lake salinity will increase, and lake productivity will decline, reducing food supply for millions of migratory birds.

Lake falls below key threshold

On the chilly, dry morning of April 1, 2022, Committee and DWP staff met on the sandy shore to cooperatively read the gauge used to measure the level of Mono Lake. We do this every year because the State Water Board rules use the lake level on that day to determine how much water DWP is allowed to divert to LA for the entire year from the tributary streams.

Because this year the result was particularly consequential, we were joined by representatives from the Mono Lake Kootzaduka’a Tribe, Great Basin Unified Air Pollution Control District, California Trout, Mono Lake Tufa State Natural Reserve, and the Mono Basin National Forest Scenic Area.

The official reading was 6379.92 feet above sea level, an inch below the 6380-foot precautionary threshold set forth in DWP’s licenses to divert water. Because the current low level is ecologically perilous, limitations designed to slow further decline of the lake take effect. For the next twelve months, DWP stream diversions cannot exceed a total of 4,500 acre-feet of water, a significant reduction from the 16,000 acre-feet allowed in the prior twelve months. However, DWP will separately be able to continue exporting more than 5,000 acre-feet of Mono’s groundwater in the Mono Craters Tunnel annually.

This respite, though welcome, is a temporary change for a year, and it comes from the same package of stream diversion rules that has left the lake far short of a healthy level. Thus, we are left with the same essential question: What is the long-term outlook for Mono Lake’s level?

Modeling Mono Lake

As the lake lingered at low levels in the 2010s the Committee responded by launching a significant effort to analyze the problem in technical detail. The lakeʼs lack of progress indicated we had a problem, but we needed a tool to project Mono Lake levels over the long term in order to understand the scale of the problem—and how to approach fixing it.

The critical tool of this effort is the Mono Lake water balance model, called the Vorster model (see blue box below), which comprehensively tallies all the water entering and departing the Mono Basin in order to simulate rises and falls in lake level over time. The Committee has been dedicating staff and resources in a methodical effort to update and refine the Vorster model, which previously ran all its calculations on a mainframe computer using out-of-date Fortran programming code. Now we are able to run the model using commonplace software and computers here in Lee Vining. Importantly, the “input hydrology” is up-to-date as well, meaning it uses the 1991–2020 hydroclimate sequence that includes recent droughts, extreme wet and dry years, and climate impacts for its calculations.

Hydrogeographer Peter Vorster, who created the model back in the 1980s and has been essential to the Committee’s advocacy for Mono Lake’s protection, joined in the modernization effort. Peter is quick to remind us that all lake forecast models are inherently flawed because they are simplifications of complex physical processes. They necessarily assume an unknown future climate, meaning that they indicate a range of possible lake levels, not what will actually occur. But forecast models are also useful, he adds, particularly when comparing results from multiple projections where one component (such as stream diversions) is varied, and the other components (such as the hydroclimate) are held constant.

How far could the lake fall if the drought continues? What rise could be expected if a record-breaking wet winter like 2017 comes around again? The Vorster water balance model can evaluate questions like these.

Most critically, the Vorster model allows us to evaluate how the State Water Board’s current stream diversion rules affect the lake’s upward progress. It also allows us to try out different rules for DWP’s stream diversions and project their impact on the lake level over a longer time span. And by utilizing up-to-date hydroclimate information, the Vorster model projects a reasonable range of possibilities for the lake level in the coming decades.

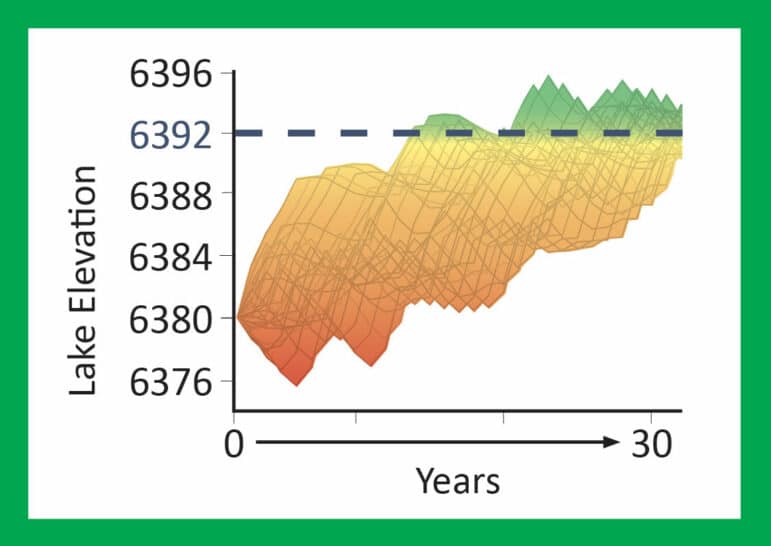

The updated Vorster model now allows us to turn observations of the lake’s lackluster upward progress into the essential question about the future: Can Mono Lake rise to the sustainable 6392-foot level with the State Water Board’s current stream diversion allocations in place? If not, would reducing or pausing stream diversions get the job done?

Will Mono Lake rise if stream diversions continue unchanged?

Will Mono Lake heal by rising to the required sustainable level in the next 30 years with stream diversions continuing at the level authorized in the existing State Water Board rules?

The model projection says no.

The takeaway: The State Water Board rules that authorize these water diversions, which were intended to result in a rising lake, are simply not going to deliver the results expected when they were written.

Will Mono Lake rise if stream diversions are paused?

We have heard concern that perhaps between drought and climate change the lake won’t rise under any scenario. The model lets us put that question to the test. If stream diversions are paused during the transition, would Mono Lake rise to the required sustainable level in the next 30 years?

The model projection says yes.

The takeaway: The current stream diversions have a real impact on lake level. Even with the drier climate of the past 30 years, Mono Lake has the capacity to rise to the management level if diversions are paused.

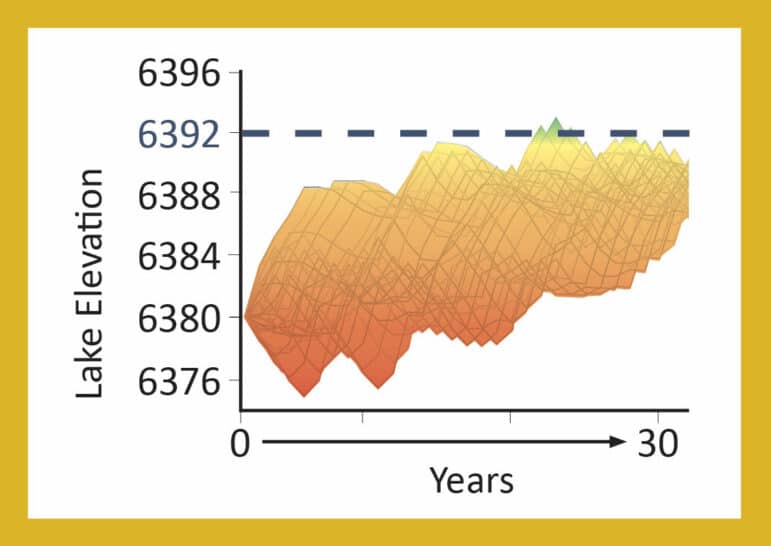

Will Mono Lake rise if stream diversions are reduced?

It is true that the more water that remains in the streams, the faster Mono Lake will rise. A year in which no streamflow is diverted is a year in which the lake receives the maximum input possible. But water policy decisions are made after considering alternatives, and a host of possible stream diversion rules exist that are reductions from the current rules but are not a full pause. The question is: How do those scenarios measure up?

We used the Vorster model to consider one such partial reduction scenario. What if the currently authorized stream diversions are cut in half?

The model projection of a 50% cutback is, well, underwhelming.

The takeaway: In this 50% scenario the lake level projection shows an upward trend in the decades ahead, but the lake falls short of reaching the mandated 6392-foot level.

Mono Lake pays for shortfalls

The State Water Board relied on water balance model projections when making the plan to halt the lake’s precipitous decline and developed the stream diversion rules to raise Mono Lake to a healthy level. The modeling work done in the early 1990s was solid, but the period of record for precipitation and runoff that the State Water Board relied on for the projections was a bit wetter than the long-term average. The past 30 years have been drier than that average, providing less water than anticipated due to slightly decreased Sierra Nevada runoff and decreased precipitation over Mono Lake. In addition, DWP stream diversion operations have been more robust than the State Water Board expected, exporting nearly the maximum allowed every year.

Under the current State Water Board rules, when there is a water shortfall while the lake is rising, Mono Lake foots the bill. DWP stream diversions don’t change unless the lake is at a critically low level. So on the way to 6392′ a dry year usually results in less water arriving at the lake while stream diversions remain constant. Over the years that debt has added up, holding the lake back on its journey to a higher level. Put another way, DWP has received the water supply benefits provided by the State Water Board decision, but Mono Lake has not received the renewed health and sustainability it was promised.

State Water Board anticipated this could happen

In the landmark 1994 decision requiring the protection of Mono Lake the State Water Board wrote that it was “keenly aware of the limitations of computer modeling hydrologic systems and the probability that future hydrologic conditions may differ significantly from historical conditions.”

Knowing that the projections of Mono Lake’s rise might not become a reality, the State Water Board stated, “If future conditions vary substantially from the conditions assumed in reaching this decision, the [State Water Board] could adjust the water diversion criteria in an appropriate manner under the exercise of its continuing authority over water rights.”

In fact, the State Water Board made a provision to hold a hearing if its expectations for lake rise were not met, and with those dates now in the past it plans to consider actions to ensure Mono Lake rises to the level it mandated. Though the hearing is not yet scheduled, the Committee’s work to prepare is already well underway.

Writing a new chapter of the Mono Lake story

The work of the Mono Lake Committee and the effort to save Mono Lake that has been embraced by so many is a work in progress. We have achieved history-making successes in environmental protection and water policy at Mono Lake.

These victories arrive as weighty words written on pieces of paper. We know that our job is to transform those words into positive changes in the landscape, bringing restoration to the streams and raising Mono Lake to the healthy level that will protect the lake and its wildlife for generations to come.

When the promises on paper aren’t transforming into real-world change, then our job is also clear. Our years of work on the Vorster water balance model now give us the ability to identify what isn’t working, and what could. Next up is the crucial work of mapping out the solutions Mono Lake needs, crafting the plan to implement them, and traveling the long advocacy road that is required to make them real.

We will look to Los Angeles, where Mayor Eric Garcetti’s major commitment to local water supplies creates great opportunities to find collaborative solutions. We will look to Sacramento, where the State Water Board will hold its hearing to consider changes to stream diversions. And we will look to Mono Lake supporters everywhere to be part of this new chapter in the story of citizen action, water solutions, and legal precedents all in service of our commitment to a simple goal: Save Mono Lake.

Mono Lake’s rise is stalled

As a result of DWPʼs past excessive stream diversions, Mono Lake lost half its volume and fell more than 45 vertical feet. The low level negatively affects the Mono Lake ecosystem, millions of migratory and nesting birds, and air quality. In 1994 the State Water Board mandated that Mono Lake rise 17 vertical feet in order to achieve ecological sustainability, restore damaged public trust resources, and minimize air quality violations. Now, 28 years later, the lake is 12 feet below the goal and only 30% of the way to 6392′.

Current stream diversions hold the lake back

A review of the conditions affecting lake level since 1994 shows that the hydroclimate was drier than was expected—with the shortfall impacting Mono Lake. Because the lake has not risen on the schedule the State Water Board expected, it will hold a hearing to consider modifying stream diversion rules to ensure the sustainable lake level is achieved. The Mono Lake water balance model uses Mono Basin-specific hydroclimate data to help us understand how lake level responds to stream diversion scenarios in drier-than-average times, and inform whether and how Mono Lake can reach 6392′.

Model shows 6392′ is possible, but only if stream diversion rules change

These graphs depict ranges of possible lake elevations under three different stream diversion scenarios. The Mono Lake water balance model processed 30 unique sequences of wet and dry years from 1991–2020 to produce the range of lake levels illustrated in each projection. This comparison demonstrates how modifying stream diversions makes a real difference in allowing Mono Lake to rise to 6392′.

Pause diversions

Reduce diversions

Continue diversions

A tool to answer lake level questions

by Maureen McGlinchy

In 1985, Committee hydrogeographer Peter Vorster published the results of his master’s thesis research, entitled “A Water Balance Forecast Model for Mono Lake.” The model quantifies 19 inflows and outflows of Mono Lake and its surrounding groundwater basin and was instrumental in informing the early court cases and State Water Board proceedings. Here at the office, we fondly call it “the Vorster model.”

A water balance model is conceptually simple: add up the inflows to the lake and then subtract the outflows. If the sum is positive, the lake rises that year; a negative sum means the lake drops. Special attention is required because of Mono Lake’s high salinity and hydrologically-closed basin, which allows direct measurements of some components but requires extrapolation from relevant data for others. For instance, stream gauges maintained by the Los Angeles Department of Water & Power (DWP) and Southern California Edison (SCE) measure runoff from eight Sierra Nevada creeks,

combining to create the largest inflow to Mono Lake. Mono Lake evaporation—the largest outflow—is primarily derived from evaporation pan measurements, adjusted for lake volume-dependent salinity and year-to-year variability.

Other inflow components of the Vorster model account for precipitation on the lake, ungauged runoff from the Bodie Hills and other surrounding mountains, groundwater inflow, and a small water import, diverted from Virginia Creek to the north. Outflow components include evapotranspiration from phreatophytes (plants whose roots access groundwater), bare ground evaporation from the exposed lakebed, evaporation from Grant Lake Reservoir and, of course, surface and groundwater exports to Los Angeles.

When lake level fluctuations over the past 20 years indicated that Mono Lake would not reach the 6392′ management level under the current stream diversion rules, the Committee undertook the task of reviving the Vorster model as a tool to better understand how Mono Lake’s level responds to changes in diversions and hydroclimate. Committee staff, under the guidance of Peter, updated the model onto a modern computer platform, identified small adjustments to a few components, and then compiled the necessary data from the past 40 years. As the accompanying graphics above show, the Vorster model can answer questions such as how much difference diversions make in achieving the management level.

DWP also utilizes a recently updated Mono Lake forecast model. Both models adequately reconstruct the observed lake elevations over the past 30 years and produce similar results looking forward. However, the models use different approaches. The DWP model is derived from the statistical relationships between lake fluctuations and the four major components of the water balance during the 1980–2019 time period. The assumption is then that these relationships will not change in a future climate. The components of the Vorster model have been developed independently of a discrete time period, which provides greater confidence and flexibility in evaluating a broader range of possible hydroclimate scenarios.

This post was also published as an article in the Summer 2022 Mono Lake Newsletter. Top photo courtesy of Lloyd Baggs.

Isn’t there a way to build some sort of instrument that collects water from the air? I’ve heard of such things being used in Africa to help people have water during a drought. I can envision hiding such instruments in the trees and letting the water they collect flow into the lake. But perhaps it would take too many of them to raise the lake level. Has anyone considered this?

Wendy Scott

Hi Wendy, thanks for sharing this idea. Raising the lake to the healthy level is important and it takes creative thinking. We aren’t familiar with the specific instrument you mention but at 45,000 acres in size Mono Lake is very large and raising it requires substantial volumes of water, like those that come from the melting winter snowpack. -Geoff