Readers in the San Francisco Bay Area opened the San Francisco Chronicle this morning to see a feature article about Mono Lake and the challenges the present-day, persistent low lake level presents for humans, birds, and the environment alike, challenges that have been exacerbated by recent droughts:

“The drought bearing down on Mono Lake and the rest of California picks up on a two-decade run of extreme warming and drying. It’s a product of the changing climate that has begun to profoundly reshape the landscape of the West and how people live within it. From less alpine snow and emptying reservoirs to parched forests and increased wildfire, the change is posing new, and often difficult, challenges.”

The article highlights problems due to the low lake level that Committee members are familiar with, in particular the increasing toxic dust storms and danger to the California Gull nesting grounds from coyotes crossing the landbridge exposed by dropping lake levels.

Mono Lake Committee Executive Director Geoff McQuilkin took Chronicle reporter Kurtis Alexander and photographer Carlos Avila Gonzales into the field when they were here to report on Mono Lake.

At Mono Lake, an emblem of the state’s wild and distinct beauty, the reckoning has been a long time coming.

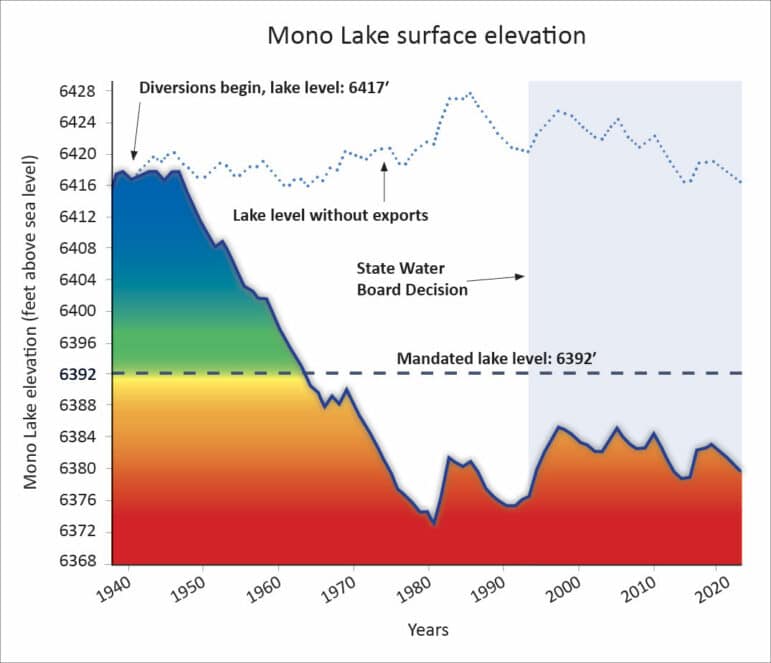

For eight decades, the city of Los Angeles has piped water from four creeks that feed the lake to its facilities 350 miles to the south, sometimes diverting almost all of the inflow. It’s a familiar California tale of old water rights yielding inordinate benefit.

The concerns at the lake, though, were supposed to have been resolved. In 1994, after a lengthy environmental campaign that spurred “Save Mono Lake” bumper stickers on vehicles up and down California, state water regulators put caps on L.A.’s exports. Slowly, lake levels rose. But they did not rise as much as they were supposed to.

Drought, on top of a climate that’s changed faster than expected, has slowed progress. On April 1, the typical start of the lake’s runoff season, the water level measured 6,379.9 feet above sea level, about 12 feet short of the state target. Before Los Angeles began drawing water from the creeks here, the lake was nearly 40 feet higher.

“A lot of Californians who know about Mono Lake think, thank goodness, we got it on the success list,” said Geoff McQuilkin, executive director of the nonprofit Mono Lake Committee, which advocates for the basin. “The thing is we’ve given it 20 years, now 28 years, and we’re still seeing the problems they thought would be gone by now.

Alexander also spoke with residents who live northeast of Mono Lake, where dust storms generated by strong winds over the dry, exposed lakebed hit people the hardest.

Fierce dust storms blow off the exposed lake bottom and cloud the skies with some of the nation’s worst air pollution.

“It affects everybody, that lake, we all live around it,” said Marianne Denny, a 40-year resident of the basin who says “the white stuff,” indicative of the lake’s decline, is among the most she’s ever seen. “Hopefully we’ll live to see more water.”

At the home of Priscilla and Cole Hawkins, the exposed lakebed on the north shore means dust, and sometimes lots of it.

“We call them dust devils,” said Priscilla, whose off-the-grid property backs up to the lake and offers big vistas of the tall peaks in Yosemite National Park, at least when the air is clear.

Cole bought the house with his wife two decades ago, moving in full-time a few years back. The dust is not a problem that often, he said, but when it is, it can be severe, limiting visibility to less than a quarter-mile. He compares the dust storms to fog banks with debris.

“When it gets really bad, we go inside or head for the hills,” he said, looking out at a blue sky on this particular afternoon. “We’ve come back to the house and it’s almost like sand on the curtains.

As Committee members know, the Great Basin Unified Air Pollution Control District monitors the air quality at Mono Lake, especially the dust storms, which have generated the worst PM-10 air pollution in the country during the last nine years. Alexander spent time with Phill Kiddoo, who keeps close track of Mono’s dust storms for Great Basin.

The dust, which is tracked by the local air district under the label PM10, or particulate matter that is 10 microns in diameter or less, is a health issue, district officials say. The particles can lodge deep in the lungs and cause tissue damage and lung inflammation.

In nine of the past 10 years, the Mono Lake area has had the distinction of racking up more federal air quality violations for PM10 than any other place in the nation, according to the district. In 2016, during last decade’s drought, federal air standards were breached on 33 days.

The past few years haven’t seen as many violations, according to data from the Great Basin Unified Air Pollution Control District. However, Phill Kiddoo, air pollution control officer for the agency, says the trend line remains bad.

“Mono Lake probably has some of the best air quality in the nation 90% of the days of the year, but on windy days, we have some of the worst,” he said.

With less snow and less runoff in the Sierra to fill the lake in recent years, Kiddoo, whose job it is to try to keep the skies clean, believes it’s time for Los Angeles to further reduce its draws from the basin.

“Every inch of lake-level rise that we can get protects air quality,” he said.

A dropping lake also increases the chances that coyotes can cross an ever-more-exposed landbridge to reach the California Gull nesting grounds near Negit Island, a problem the Committee has been vigilant about in recent years.

Because of the unique environment, the lake’s inhabitants are limited: mainly brine shrimp and hovering alkali flies. These critters, though, provide food for as many as a million migratory birds annually, including eared grebes and Wilson’s and red-necked phalaropes.

McQuilkin is watching, in particular, the California gulls. He wants to make sure they’re safe. During the summer, about a quarter of this gull’s total population nests on the lake’s Negit Islets, which are at risk of being invaded by predators because of a land bridge emerging in the increasingly shallow water. The birds already abandoned one of the main islands, Negit Island, decades ago because it became connected to the mainland with lower lake levels.

“There’s no question that coyotes can swim across that,” McQuilkin said, looking at the channel between the current islands and the north shore. “We’re just hoping they don’t.”

Five cameras that McQuilkin and his colleagues have set up monitor for coyotes. The Mono Lake Committee keeps more than a mile of electric fence on hand that employees plan to string out if the wild canines begin to amass. So far, the cameras have picked up just two passers-by.

The group debuted the temporary barrier during last decade’s drought, when coyotes started making their way to the islands and scouting for eggs and young birds.

This year, the group hopes the lake bottom will remain partially submerged at least until next month, when most of the newborn gulls will have hatched and be ready to fly off to places like San Francisco Bay.

Next year is a different story. Even if the Sierra gets a lot of snow come winter, melt-off into the lake won’t arrive until late spring and summer, so lake levels will likely be even lower when the gulls return. McQuilkin said the fence will almost certainly go up then.

The State Water Board, which set the rules to protect Mono Lake back in 1994, told Alexander that it’s time to start evaluating the next steps for re-evaluating the rules in order to get Mono Lake to rise.

The State Water Resources Control Board, which regulates water draws, told The Chronicle that it is paying attention to the lake, the basin and to the thirst that’s compromised them.

While acknowledging that the lake’s rise has stalled — lake levels have generally hovered a little more than 10 feet below the target for a decade — state officials credit water restrictions for at least stabilizing things.

Owens Lake, about 150 miles to the south, was not so fortunate. The lake was sucked dry by Southern California water diversions almost a century ago and is nothing but salt flats today.

The 1994 regulation at Mono Lake established caps on how much Los Angeles can draw from the feeder creeks based on how high the lake is. This year, the city’s diversions were limited to 4,500 acre-feet of water, about enough to supply 60,000 residents, according to the city. If the lake had been three feet lower, no water could have been drawn.

Erik Ekdahl, a deputy director at the State Water Board, said the changing climate, notably the “aridification” of the West, has constrained lake levels more than regulators anticipated and the agency will likely have to re-evaluate its regulation.

“We are at the point where we do want to start asking, ‘What are the next steps?’ and ‘What’s the timeline for having a more thorough discussion?’” he said.

Alexander received an emailed response from DWP disputing their clear role in Mono Lake’s precipitous decline in the 20th century and its current predicament today.

The Los Angeles Department of Water and Power insists that whatever comes of future deliberations, more water restrictions are not the answer.

In an email to The Chronicle, the department’s managing water utility engineer, Paul Liu, said the city’s draws had a negligible impact on the lake’s decline, compared to drought and other climate factors.

The city, in recent years, has reduced diversions to about 12% of the water in the creeks flowing to Mono Lake where it has water rights, he said. Meanwhile, the city has spent tens of millions of dollars to help restore the creeks and promote healthy runoff. About 3% of the city’s total water comes from these creeks, Liu said, a supply that is small but considered vital.

“In a scenario where Mono basin exports to Los Angeles are reduced or cut off completely, that shortfall will have to be made up by increasing exports from the State Water Project or the Colorado River, which are both extremely strained and limited as well,” wrote Liu.

DWP’s statement that “the city’s draws had a negligible impact on the lake’s decline, compared to drought and other climate factors,” tries to sweep a lot of history under the rug. DWP’s unrestrained decades of diverting the total flow Rush, Lee Vining, Parker, and Walker creeks are the reason Mono Lake shrank in size to the perilously low level that remains frustratingly persistent today.

It is well established what is needed to protect Mono Lake, put an end to the dust storms, and protect the habitat of millions of migratory and nesting birds: raise the lake to the sustainable level of 6392 feet above sea level. It’s what the State Water Board ordered to protect the lake—a mandate the Mono Lake Committee and Los Angeles agreed to implement together.

Since we now see that the stream diversion rules set in 1994 aren’t delivering that rise, the Mono Lake Committee, thanks to support from members, is working to develop a new plan using our hydrologic model to look at changes to DWP’s diversions to get the job done. The good news: A pause to DWP’s stream diversions would allow Mono Lake to rise and achieve its mandated healthy level. As Geoff told the Chronicle, and as Committee members know: “Californians do not want to let this go.”

Top photo courtesy of Carlos Avila Gonzalez/San Francisco Chronicle.