The Mono Lake Committee’s decades-long effort to secure new local recycled water for Los Angeles, and effectively replace stream diversions from Mono Lake, may be on the precipice of finally being realized.

The story begins in the 1980s when the Los Angeles Department of Water & Power (DWP) argued that any reduction in its Mono Lake exports would force Los Angeles to secure water from other places, hurting Southern California or the San Francisco Bay Delta.

We said no. There had to be another solution.

Los Angeles and Mono Lake shared the same need: reliable and adequate water supply. So, the Mono Lake Committee set out to help Los Angeles develop projects to create reliable water supplies within the city, so that Mono Lake could be saved and DWP would not transfer the problem to another place or community.

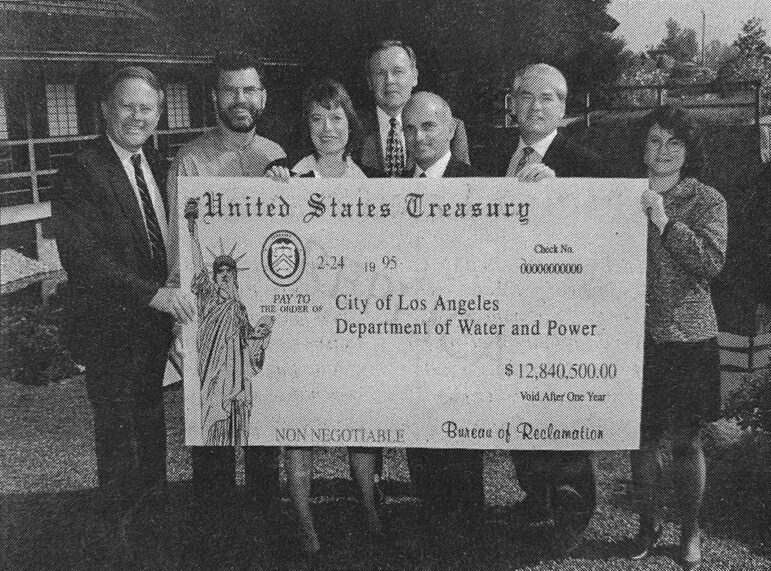

By 1992, the Committee had secured over $100 million in state and federal funds to support DWP’s water conservation and recycled water projects. The federal money came through the US Bureau of Reclamation’s Title XVI Program and would fund 25% of the cost of building DWP’s first major recycled water project.

Unbelievably, DWP refused to accept the money, unwilling to admit that there was a solution that met our shared needs.

After years of bitter conflict, LA’s Mayor and City Council overruled DWP’s attorneys and agreed to accept both state and federal funds in December 1993. The money would support building new recycled water infrastructure at the existing Donald C. Tillman Water Reclamation Plant in the San Fernando Valley, and the new, potable water created would permanently replace the water previously taken from Mono Lake.

California Governor Pete Wilson attended the City’s press conference, hailing the consensus settlement as “a victory for the people of Los Angles and every Californian.” In a private note to the Committee, the governor lauded our work, saying that it “set a high standard for resolving environmental issues. This common-sense approach will protect California’s environment for generations to come.”

Despite statewide accolades and significant funding support, the recycled water project was derailed in 2000 due to inaccurate publicity about recycled water safety. The Tillman plant was completed, but only about 8,000 acre-feet annually ended up replacing existing potable water use.

DWP has never acknowledged that those 8,000 annual acre-feet were part of LA’s historic agreement to protect Mono Lake.

Fast forward to this year, late summer—an event held at the Tillman Water Reclamation Plant. Over 150 city and community leaders gathered with DWP and LA Sanitation & Environment in a big construction hanger to celebrate the expansion of the original recycled water project begun decades ago. Now called the LA Groundwater Replenishment Project, it will deliver all of the recycled water the original project was intended to deliver, and more.

The $740 million LA Groundwater Replenishment Project adds a series of water purification treatments, including membrane filtration, reverse osmosis, and ultraviolet oxidation, and then, using the pipeline from the original project, recharges the groundwater table for future extraction. When finished in 2027 the project has been advertised to yield 22,000 acre-feet of treated recycled water annually—a new local source of drinking water for LA.

At the event, much to everyone’s surprise, DWP Commission President Richard Katz announced that the project is now expected to yield 40,000 acre-feet annually, more than doubling the originally expected water yield.

Back in 1993, then-State Assemblymember Katz was a key speaker at the press conference alongside Governor Wilson, LA Mayor Richard Riordan, the Mono Lake Committee, and other city and legislative leaders—celebrating LA’s decision to use Tillman’s recycled water to protect Mono Lake.

Decades later, now-DWP Commission President Katz explained to the crowd that the increased production to 40,000 acre-feet annually was a “new” and “unexpected” water supply—additional water that he hoped would enable DWP to reduce its remaining 16,000 acre-feet per year of water diversions from Mono Lake in order to allow the lake to rise to the State Water Board-ordered healthy management level of 6,392 feet.

This really could be the opportunity for LA to bring the recycled water solution for Mono Lake full circle.

To be clear: Hope is not the same as a firm commitment that Mono Lake will benefit from this new supply of water But President Katz’s statement is welcome news because it means LA will have additional water it can rely upon while also complying with its obligation to raise Mono Lake to the State Water Board-mandated healthy level. It’s time for this replacement water, forged when there was no other solution, to benefit Mono Lake.

There is also a more fundamental point here. As we cope with climate change impacts, we can affirm our capacity to share water with special places like Mono Lake so they can thrive alongside people and cities. We cannot accept choices that don’t offer real solutions. We must work to find those solutions and make them possible.

Three decades ago, the City of Los Angeles made the choice to protect Mono Lake and the world applauded. The question today is whether Los Angeles’ leadership will finally fulfill its promise to save Mono Lake by raising the lake to State Water Board-mandated protection level.

This post was also published as an article in the Fall 2025 Mono Lake Newsletter. Top photo courtesy of Adi Liberman: Committee Board member Martha Davis, right, speaks at the recent event celebrating the expansion of water recycling to generate more local water for LA than is diverted annually from Mono Lake.