On May 15th every year, the Los Angeles Department of Water & Power sends its Mono Basin compliance report to the State Water Resources Control Board. One of the notable things about the May 15, 2014 report is that it does not contain a “tributaries” section for the first time. This indicates that there was no official geomorphic or vegetation monitoring along the streams in 2013, for the first time since the State Water Board issued Order 98-05 in 1998. A reduction in stream monitoring has begun, and aside from a small increase in effort to confirm the effects of the new streamflows, this reduction was anticipated in the Mono Basin Stream Restoration Settlement Agreement.

The Committee has begun reviewing the report, which contains five sections that can be found here: a cover letter, the status of restoration compliance, an operations plan, a fisheries monitoring report, and a waterfowl and limnology monitoring report.

We turned to the limnology sections of recent compliance monitoring reports this week because we have noticed that Mono Lake is turning green and the brine shrimp population appears to be declining. Typically, we assume that in June the brine shrimp population increases and water clarity increases as the algae is grazed. June is a transitional month in the lake, but it is more complex than that.

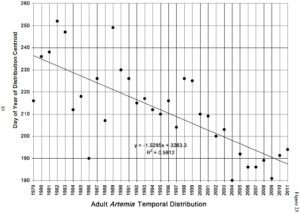

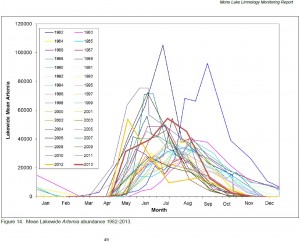

There are (at least) two generations of brine shrimp each summer; the first generation of adults usually peaks in May–June and the second peaks in August–September. If the first generation is large, and eats all the algae, the second tends to be smaller, and vice versa. The shrimp in the warmer northeast side of the lake tend to develop ahead of those in the southwest. After meromixis breaks down, as it did at the end of 2012, for various reasons shrimp abundance tends to be very high. And as salinity declines as the lake rises, the shrimp tend to hatch earlier in the year. Amidst all this complexity, weather patterns have an influence as well.

The 2012 limnology monitoring found that the summer adult shrimp abundance peaked in May, centering on June 27th, the earliest on record. This is consistent with the long-term trend. Adult shrimp abundance in July 2012 was the second-lowest recorded in July in over 30 years of monitoring.

The 2013 limnology monitoring found, on the other hand, that July adult shrimp abundance was the second-highest on record. This is consistent with high abundances in years following the breakdown of meromixis, as in 1989 and 2004.

So what is happening in June–July 2014? Why is the lake turning green? There have been recent reports of incredibly high densities of brine shrimp in certain areas of the lake, and incredibly low abundance in other areas. We don’t have the results of the 2014 limnology monitoring yet, but the likely explanation is that we are in between the first and second generations of brine shrimp. Will we have a year like 1981 or 1989, with a huge second generation of shrimp? Or will we have a year like 1993 or 2012, where the peak was very early and the June decline continues the rest of the summer? The long-term trend favors the latter explanation, but we shall have to wait and see.

good article in that it explained things well even for a lay person. good summary at end to put things in perspective