Continuing DWP water diversions and decades of low lake levels causing harm

For centuries California Gulls have migrated east across the Central Valley and Sierra Nevada to nest at Mono Lake. Their graceful, raucous, and quirky presence is a distinct and iconic part of the Mono Basin along with granite peaks, brine shrimp, tufa towers, and volcanic islands. For generations gulls have played an important role in the biodiversity of the Mono Basin and Eastern Sierra, and their health is a measure of the health and abundance of the Mono Lake ecosystem.

Now, three decades after the California State Water Resources Control Board ordered that Mono Lake must be allowed to rise to 6,392 feet above sea level—which it has not yet reached—California Gulls are not only struggling to recover, they’re also struggling to survive. A new report documents record nest failure last year, signaling serious trouble for the gull colony as chronically low lake levels and continuing stream diversions by the Los Angeles Department of Water & Power (DWP) are damaging the lake’s ecological health.

A legacy of gull research

Research on California Gulls at Mono Lake began five decades ago as excessive water diversions came dangerously close to eliminating the gull colony. Public and scientific concern intensified around DWP’s damaging exports that had pushed the lake lower, to the brink of ecosystem collapse. In 1979, the low lake level exposed a landbridge enabling coyotes to prey on thousands of chicks on Negit Island, routing the gulls away from their native colony. As an indicator of Mono Lake’s plight, gulls became a rallying call for the protection of the lake, and the impetus for gathering important population data.

The issue was, literally, explosive at the time. The California National Guard attempted to blast a channel into the landbridge to protect the gulls from coyotes (see Summer 1979 Mono Lake Newsletter). The detonations were dramatic but did not make a difference in the landbridge. However, they did make a difference in news coverage and public attention toward birds and Mono Lake. The potential loss of gulls and the lake’s ecosystem were motivating reasons for the founding of the Mono Lake Committee in 1978.

Explosions failed, as did early attempts to fence out coyotes. In the chaos and disruption of coyote predation, the gulls moved to nearby islets that remained isolated from the landbridge and surrounded by deeper water. Early monitoring began during this traumatic time for the gull colony, and consistent annual monitoring was essential to understanding if the gulls would survive. In 1983, Point Reyes Bird Observatory (now Point Blue Conservation Science) began that work, which is now in its 43rd consecutive year and among the longest studies on colonial waterbirds. The continuity of the research is impressive, and a testament to the importance of California Gulls in the Great Basin and Pacific Flyway. The gull study continues to provide a detailed barometer of gull nesting success at Mono Lake and its connection with the lake’s health and productivity.

Decades of gull research has chronicled change—a journey from near collapse of the colony to rebounding populations. But the data now show a spiraling population and reproductive decline.

Lakewide nest failure

In 2024, Point Blue’s monitoring detected an alarming collapse in chick hatching and survival. Thousands of California Gulls arrived to nest at Mono Lake like they do each season, reuniting with their partner in the same scrape of ground as the previous year. Like other species of gulls, California Gulls depend on stable, predator-free nesting habitat and reliable food to raise their young. But unlike many other species of gulls, California Gulls have an ecological history of migrating inland to breed. Mono Lake and Great Salt Lake have historically been home to the largest native California Gull colonies within the birds’ range.

Nest monitoring at the end of May 2024 indicated that thousands of birds were nesting. The gulls were incubating eggs in nests and preparing for chicks that usually hatch during June. Researchers returned in July to once again survey the colony with specially permitted drones to take high-resolution imagery. A few chicks were visible, but the researchers noticed something was different—there appeared to be fewer nests and chicks and some of the surveyed islets unexpectedly had few, if any, gulls. After a thorough analysis of the imagery and data, a sobering picture emerged: there was a near total nesting failure. Over 20,000 adult gulls fledged just 324 chicks lake-wide. The year before, in 2023, approximately 11,000 chicks were produced. According to Point Blue’s 2024 report, “This total chick production is by far the lowest we have ever documented at Mono Lake.”

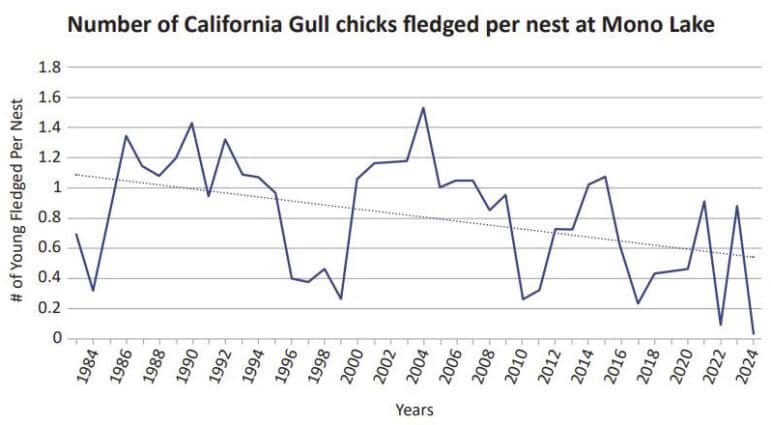

Reproductive success for the year is measured in the number of chicks fledged per nest. The long-term average through 2023 is 0.83 chicks per nest. In 2024 this number was 0.032 chicks per nest—the lowest figure ever documented at Mono Lake, and lower by nearly a factor of three compared to the previous record low of 0.09 in 2022. The overall success rate has declined an average of 0.013 chicks fledged per nest per year, or 500 fewer fledglings per year since the study began in 1983.

The nesting failure in 2024 is ominous, and the long-term trend in gull numbers at Mono Lake is not reassuring either. Fewer and fewer gulls are returning to nest because it’s becoming increasingly difficult to raise chicks and maintain the population. The estimated 20,258 California Gulls that came to breed at Mono Lake in 2024 was an all-time low based on 10,129 nests counted—well below the 1983–2023 average of 42,575 adults.

Gulls have been able to rebound from the occasional bad year of nesting as long as sufficient food and predator-free conditions prevail. But recent nesting data and observations reveal that uncertain food timing and productivity and recurring coyote predation—all due to low lake levels—are likely causing disruption. Gulls are having more difficult years for nesting, which is causing a decline in the overall population at Mono Lake.

According to Ryan Burnett, the lead gull researcher and Sierra Nevada Group Director for Point Blue, commenting on the gulls’ downward trend, “When it’s good, it’s never as good as it used to be, and when it’s bad, it’s worse than ever.”

Gulls need a healthy lake

For three decades Mono Lake has cycled up and down in elevation, all the while failing to achieve net progress toward the level that the State Water Board recognized would ensure the protection of California Gulls, ecosystem health, air quality, and recreational and scenic values. Each time the lake rises up from a low level, the ecosystem is vulnerable to persistent stratification. Each time the lake declines, the gulls are faced with the threat of predation. The longer the cycle continues, the longer the gulls must wait to return to nest on Negit Island, and the longer they must cope with transient habitat that is getting overrun with invasive weeds.

The gulls are caught in a doom loop of compromised lake productivity, predation threats, and weeds—all the result of DWP’s water exports under diversion rules that clearly need revision.

Low food supply linked to gull nesting failure

For nesting gulls to succeed, they must have sufficient caloric energy to invest in egg laying, feeding their chicks, and feeding themselves. Brine shrimp are a critical food source for the gulls each spring, and if the shrimp don’t appear in sufficient numbers and size at the right time for the gulls, it impacts nesting success. A condition called meromixis, or persistent stratification of the water column, influences the productivity of algae and shrimp, which in turn influences the food chain all the way up to the top predator—gulls. While the relationship is not absolute each year meromixis occurs, it is a statistically significant factor in predicting annual nesting success.

What is meromixis? In simple terms, it’s a water density stratification that continues for multiple years. Mono Lake goes through chemical and thermal stratification cycles annually, but meromixis occurs when a less dense, “fresher” lake-wide lens of water persists on top of denser, hypersaline water below. When Mono Lake is chronically low, it’s more vulnerable to meromictic events, especially after a big winter, when substantial snowmelt in the spring flows into the lake. Large inputs of stream water do mix with the lake, but the upper layers of the lake remain less saline overall. The deeper, more saline water ends up temporarily trapping nutrients that would otherwise cycle throughout the lake in a year with closer to average runoff. This means that the following year the algae has less available nutrient mass to incorporate for growth, reducing its overall productivity. Brine shrimp feed on the algae and are also negatively impacted by the temporary loss of nutrients within the lake ecosystem.

Gulls famously take advantage of many food sources throughout the year, but they depend on abundant brine shrimp when nesting. According to the 2024 Point Blue report, “The production of chicks at Mono Lake is almost certainly directly tied to the lake’s production of food resources the gulls rely on.” If shrimp productivity is lower, or shrimp growth is underdeveloped or delayed, the colony is significantly impacted. The report continues, “the lake conditions that resulted in these patterns in the shrimp population were not compatible with the gull’s ability to raise young, leading to a near-complete breeding failure in two of the last three years.” Simply put, in 2024 the gulls nested. They laid eggs. And then, it appears, they found there were not enough brine shrimp in the lake to sustain the final stage of hatching eggs and raising chicks.

Mono Lake is currently meromictic after the significant 2023 runoff year, which was close to 200% of average. How long stratification persists, and the rate at which it breaks down is related to a host of variables, including wind, weather, drought, diversions, and the level of Mono Lake.

The higher the level of Mono Lake, the less vulnerable it is to large inputs of fresh water causing stratification. Before DWP’s diversions began in 1941, Mono Lake was much larger and less saline, allowing it to reliably mix each year even with large inflows of fresh water from big winters.

Since the early 1980s when meromixis was first detected in Mono Lake, there have been six documented multi-year episodes. This has affected algae, brine shrimp, and gulls repeatedly (and likely other birds like Eared Grebes), and these events are emerging as a new, dysfunctional ecological pattern as Mono Lake fluctuates ten feet below its mandated, 6,392-foot level. Decades of maximized diversions damaged the lake’s ecosystem, and now the current level of diversions allowed since the 1994 State Water Board Decision are preventing recovery and likely causing additional harm the longer they continue.

Invasive weeds, too

California Gulls remain displaced from their native nesting habitat on Negit Island. Since 1979 gulls have nested on nearby islets where they have managed until recent years. Now, as the islets’ rocky and sandy habitat has been exposed to five decades of precipitation, salts have been reduced from the soils, making them more hospitable to invasive weeds. One weed, called Bassia or smotherweed (Bassia hyssopifolia), has become widely established and is diminishing available nesting habitat.

Bassia has been documented in the Mono Basin since the 1950s, but only since 2012 has it reached and invaded the Negit islets. The problem with Bassia is that it grows up to four feet tall and, while it is an annual weed, its skeletal structure remains from year to year rooted in large mats or stands that reduce open nesting habitat for California Gulls. Gulls nest on the ground in open, sandy, rocky terrain. Bassia chokes off nesting habitat, leaving the gulls with less space and fewer options.

The Mono Lake Committee and the Inyo National Forest worked cooperatively to burn Bassia from Twain Islet in February 2020 (see Winter & Spring 2020 Mono Lake Newsletter). The burn was extremely successful for the gulls, resulting in an increase of 3,000 new nests on Twain the following nesting season. However, Bassia returned after well-above average precipitation in 2023. Committee staff and volunteers have worked to hand-pull and clear the weed, prior to and after that year’s nesting season, which helped. Unfortunately, Bassia has rebounded in treated areas and another burn may be necessary. The only long-term viable nesting option for the gulls is to return to their original nesting habitat on Negit Island, where Bassia does not dominate. For that to happen, Mono Lake must rise to the healthy level required by the State Water Board.

Coyote roulette

While meromixis and weeds put significant pressure on the gulls, coyotes remain an acute threat. DWP lowered Mono Lake so dramatically that coyote predation remains a critical, periodic danger to nesting California Gulls. The fluctuating lake level remains below what is needed to effectively submerge the landbridge. The State Water Board recognized in its 1994 decision to protect Mono Lake that, “a lake level of 6,384 feet would protect the gulls from coyote access to Negit Island and nearby islets and would maintain a buffer for continued protection during periods of extended drought. A water level of 6,390 feet would completely inundate the landbridge between Negit Island and the shore and would provide additional deterrence to potential terrestrial predators.”

Yet Mono Lake’s 25-year average elevation remains two feet below 6,384 feet, and a full ten vertical feet shy of the healthy management level. Nesting gulls are continually in jeopardy when low lake levels allow coyotes to cross shallow water and the landbridge. The birds have suffered repeated predation events on the Paoha and Negit islets, further eroding their population at Mono Lake. Coyote predation in 2015 and 2016 resulted in fewer nesting gulls.

In 2017 the Committee installed a temporary electric fence across the landbridge to prevent coyotes from reaching vulnerable nesting gulls after the 2016 predation event (see Summer 2017 Mono Lake Newsletter). The fence worked and the gulls were protected, but it was only through a significant dedication of time and resources and some luck that the effort succeeded. The lake rose significantly in 2017 after the gulls nested and the fence was dismantled. Installing a fence is not a long-term, tenable management strategy that can replace a higher lake level. Waiting for the benefit of a wet year remains frustratingly futile for managing coyote predation—doubly so when DWP water exports routinely erode the wet-year lake level gains that could otherwise protect against both predation and meromixis.

Are we running out of time for the gulls?

California Gulls are resilient, but they are not invincible. They have, remarkably, weathered the predation-induced trauma of the initial big drop in lake level caused by DWP diversions. After that, gull numbers sharply rebounded, indicating that if healthier ecological conditions and predator-free conditions were available, they could thrive.

Mono Lake is only halfway to the State Water Board’s healthy level requirement and the lake level is insufficient to maintain a long-term, sustainable nesting population of California Gulls. If the lake does not achieve constant progress toward its management level soon, the Mono Lake Committee is concerned that the second largest California Gull colony in the Great Basin may slip away.

What the gull situation shows us is that climate change and increasing extreme precipitation volatility are not the problem here. The problem is DWP’s continuing, maximized diversions that remove inches a year and feet per decade from Mono Lake, keeping the lake low and vulnerable to a permanent loss of biodiversity.

Ironically, as the size of the gull colony has diminished, the water supply portfolio of DWP has grown to be more efficient, and resilient as Los Angeles enjoys the lowest per-capita water use in its history. The city only draws 1–3% of its water from the Mono Basin, but DWP continues to gamble away Public Trust values and biodiversity while maintaining that everything is fine at Mono Lake.

The California Gulls are telling a different story—and it is not a hopeful one for the other birds and organisms that are also hanging on for a long-overdue healthier Mono Lake.

This post was also published as an article in the Summer 2025 Mono Lake Newsletter. Top photo by Sara Matthews.

This is REALLY depressing. We cannot allow LADWP to continue to divert so much water and I also understand that they have recently broken a promise to restrict their diversion this or last year?

Hi Henry, yes, it is really depressing. Last year DWP abandoned the LA Mayor’s promise to restrict its diversion but this year it intends to take the full amount they are allowed.