Better operating rules needed for Mono Lake to rise

Water diversions to Los Angeles—and away from Mono Lake—began just after noon on January 31. With the turn of a control wheel, the Los Angeles Department of Water & Power (DWP) opened the aqueduct, sending Mono Basin water into the Mono Craters tunnel and on a 300-mile journey down the aqueduct system.

Mono Lake, of course, would be better off with that water flowing down Rush Creek instead, entering the lake and helping maintain the significant—but far from complete—lake rise of last year.

This spring DWP faces an even bigger choice. On April 1, the maximum limit on water exports will increase nearly fourfold. Will DWP choose to maintain the same export level as recent years? Or will it choose to quadruple its water diversions—and push Mono Lake’s level downward?

For three decades, DWP diversion operations have been frustratingly blind to the requirements for Mono Lake’s protection. This year could be different if LA chooses wisely.

This year is also shaping up to be the year for action on the California State Water Resources Control Board’s rules that govern the DWP diversions, and the flaws that have become visible over the 30 years since those rules were set forth. The Mono Lake Committee is exploring new dynamic concepts to fix those problems, and the State Water Board is moving closer to holding the hearing necessary to make changes.

Local water for Los Angeles

Three days after water exports began in January, an atmospheric river storm swept into California, highlighting DWP’s opportunities to meet the city’s water needs with local supply rather than continuing the damage of decades of excessive water diversions at Mono Lake.

By February 3 the Los Angeles River was rushing with stormwater. In just four hours the equivalent of the entire volume of 2023 Mono Basin diversions flowed past downtown LA. That stormwater went straight to the ocean.

Water leaders, the mayor, city council, and the Mono Lake Committee all support expansion of stormwater capture—and other sustainable local supply projects—to meet the city’s goal of securing 70% of supply from local water sources by 2035.

Indeed, DWP is making progress on achieving the mayor’s goal of gathering 150,000 acre-feet of the city’s water through local stormwater capture. Yet at Mono Lake, DWP decided to set aside consideration of the State Water Board’s now decade-overdue lake level requirement and simply divert the maximum amount of water the Board’s operating rules allow.

DWP’s choice to maximize diversions

DWP has chosen to take the maximum amount of water it legally can every year since the State Water Board decision was made 30 years ago. DWP often implies it must take the maximum amount of water away from Mono Lake, yet the official water rights require no such thing. They say DWP has an opportunity to divert, not a requirement, and the amount can be any amount “up to” the year’s specified maximum.

For three decades, DWP diversion operations have been frustratingly blind to the requirements for Mono Lake’s protection. This year could be different if LA chooses wisely.

The formula to allow Mono Lake to recover from DWP’s history of excessive water diversions is simple: maximize the gains during wet years and minimize losses during dry years that inevitably follow. Big lake level gains, like last year’s, are eroded by diversions in subsequent years, setting back the restoration effort.

For example, DWP diversions at maximum levels will consume three feet of Mono Lake level over the next decade. And it adds up. Mono Lake would nearly be at the Public Trust protective level today but for the diversions DWP has taken since the 1994 State Water Board decision.

The choice facing DWP

DWP has a big decision to make in 2024. A higher Mono Lake means State Water Board diversion rules, unfortunately, will nearly quadruple the maximum allowance for water diversions. Experience shows this formula isn’t working. Lingering low lake levels perpetuate ecological, Tribal, economic, and air quality harm that DWP’s decades of excessive diversions have caused.

The city is already running on 4,500 acre-feet of diverted Mono Basin water, and even did so during the height of the drought back in 2015. And that’s on top of the 5,500 acre-feet of Mono Basin groundwater that flows to LA every year on average. Coming off the very wet 2023 winter, reservoirs and supplies are ample. Stormwater capture is at an all-time high and per capita use is low, reflecting the successful conservation efforts of Angelenos.

Clearly the city doesn’t need to take more. But will DWP do it anyway in 2024?

Can DWP choose to hold itself back from repeating a 30-year pattern of maximizing water diversions? It’s a key moment of opportunity for LA leadership to show commitment to meeting the city’s agreed-to obligation to protect Mono Lake. It will also be a preview of what to expect from DWP at the upcoming State Water Board hearing. Will DWP choose to help solve the problem? Or will they fight to maintain the flawed status quo?

Flawed stream diversion rules

The fact that the lake’s big 2023 rise lifts the cap on the amount of allowed water diversions raises another question: Why would the State Water Board allow that?

Well, the rules were set 30 years ago in the landmark Decision 1631. And a look back reveals a simple answer: based on analysis at the time, the Board expected the rules would work, allowing the lake to rise to the Public Trust lake level of 6,392 feet above sea level in about 20 years, even with as much as 16,000 acre-feet of water diversions allowed by operating rules along the way.

Now, a decade past that delivery date, it’s easy to see that the 1994 diversion rules haven’t worked to get the job done. Hydrologic modeling projects more of the same in the future.

That’s what the State Water Board hearing will be all about: crafting and implementing better operating rules that fix the flaws so that the lake can rise to the long overdue level. It’s a plan the Board itself made, just in case the 1994 diversion rules didn’t work.

The hearing will be a chance for the State Water Board to review the maximum diversion specifications. More than that, it will be a chance to restructure the operating rules to be more dynamic and responsive to the changing climate and changing hydrology of the Mono Basin.

Fixing the flaws

How might the State Water Board fix the flawed stream diversion rules? The Committee has been studying and modeling the question carefully.

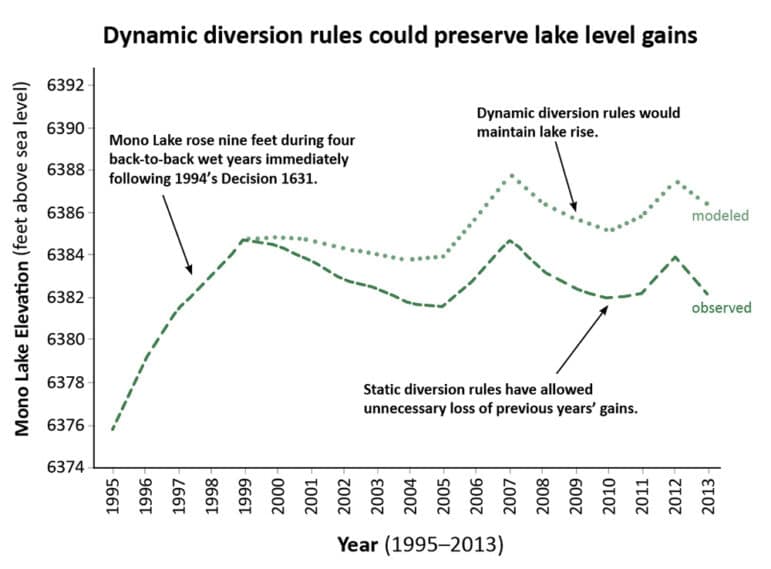

Adjusting diversion volumes is part of the answer to be sure. However, we have found that the overall structure of the rules needs fixing too. After last year’s significant lake rise, current rules allow DWP to divert until that gain is lost and the lake falls back into critically low levels like 6,380 and 6,377 feet. Only then do cutbacks on diversions activate, and these three-decade-old lake thresholds allow the rollercoaster of lake rise and fall to continue. Thirty years ago it made sense for the 6,377-foot level to trigger a halt to water diversions because back then the lake was at 6,375—below the threshold. But as the lake rises the threshold has never changed.

Rules that control diversions based on lake level make sense, but the thresholds are static and hardwired into the current stream diversion rules. They don’t have to be.

A better approach is to design rules that automatically adjust, so that the lake level thresholds controlling diversions move upwards in response to lake rise. For example, the lake rose nearly five feet last year, and the zero-diversion threshold could dynamically “ratchet” upward as well, moving from 6,377 to 6,382 feet above sea level.

Why let DWP diversions push the lake all the way back down to where it was 30 years ago? Instead, implementing “dynamic” rules of this kind would lock in gains as they happen.

Dynamic rules, with lake threshold requirements that ratchet upward right along with the lake as it rises, have great potential. The Committee team is using hydrologic modeling to explore many scenarios that use the dynamic concept and compare their effectiveness against the static rules. So far the results show that incorporating dynamic rules would be a significant fix to the State Water Board’s flawed original rules.

We’re also taking the concept to the collaborative technical workgroup meetings, underway since last year, that bring together model experts from the California Department of Fish & Wildlife, DWP, and the Committee.

A big year ahead for Mono Lake

It’s a big year for Mono Lake, the Committee, and all of us who are committed to seeing the right thing done to protect and restore this special place.

Los Angeles will be making a choice about increasing water diversions—and Mono Lake impacts—in the next few months. You can be sure the Committee team of staff, experts, and attorneys is engaged to advocate for the right outcome for the lake.

The technical modeling collaboration will continue, and we will work to be sure useful information is the result, laying out scenarios that incorporate new ideas like dynamic rules to identify solutions for the future.

At the same time, we are already mobilizing in preparation for the State Water Board hearing. It’s the place to fix the flawed diversion rules, and the broad call for action at last year’s Board workshop still resonates. Though there is not yet a date on the calendar, the State Water Board elevated Mono Lake and the hearing into its 2024 priority workplan in February, signaling that public and Board concern, and the actual peril of lower lake levels, are compelling reasons for action.

All in all, it will be a very busy year of advocacy for Mono Lake—and new choices and new rules that will lift the lake into a new era of health.

This post was also published as an article in the Winter & Spring 2024 Mono Lake Newsletter. Top photo by Elin Ljung.